In the past we have discussed that some investors demand dividends. (Here is a nice post by Larry Swedroe on the topic and there are more holistic measures, such as shareholder yield, which are better predictors of future returns). A few posts we have on the topic highlight that CEOs cater to dividend demand, Mutual funds “juice” the dividend yield, and examine the returns to dividend payers in payment months. These papers support the behavioral finance view of the financial marketplace.

Behavioral finance experts, Samuel M. Hartzmark and David H. Solomon, have a new working paper titled, “The Dividend Disconnect,” which examines investor behavior around dividend paying firms. The paper highlights the fact that humans use mental accounting and this affects decisions that investors make regarding positions in their portfolios.(1)

This paper has two primary predictions, which we will describe below.(2)

- Capital gains and dividends are viewed as distinct desirable attributes(3)

- The free dividends fallacy: separate evaluation leads to neglect of the tradeoff between price changes and dividends

The Dividend Disconnect Summary

The first prediction in the paper is that, “Capital Gains and Dividends Viewed as Distinct Desirable Attributes.”

But what does that mean?

The authors highlight that when assessing stock positions, an investor has two options for how to assess the performance — (1) simple price appreciation/depreciation, or (2) total return. Note that price appreciation/depreciation is simply the price appreciation/depreciation on the position, while total return includes both the price appreciation/depreciation plus the dividend return.

Directly from the paper:

For many positions, either price changes or returns including dividends will yield the same category of gain or loss. However, some positions are at a gain when dividends are included, but at a loss without their inclusion. Do investors treat such positions as being at a gain or at a loss when evaluating whether to sell the position? This is equivalent to asking whether investors adjust for the mechanical decrease in shares price that results from dividend payments.

To test this, the authors regress a sell signal against two variables:

- Unambiguous Gain: A dummy variable (0/1) — A value of a 1 if the position is at a gain only including price appreciation (no dividends)

- Gain only with Dividends: A dummy variable (0/1) — A value of a 1 if (1) the stock position is classified at a gain if one includes dividends (total return), but also (2) at a loss if one only examines price appreciation.

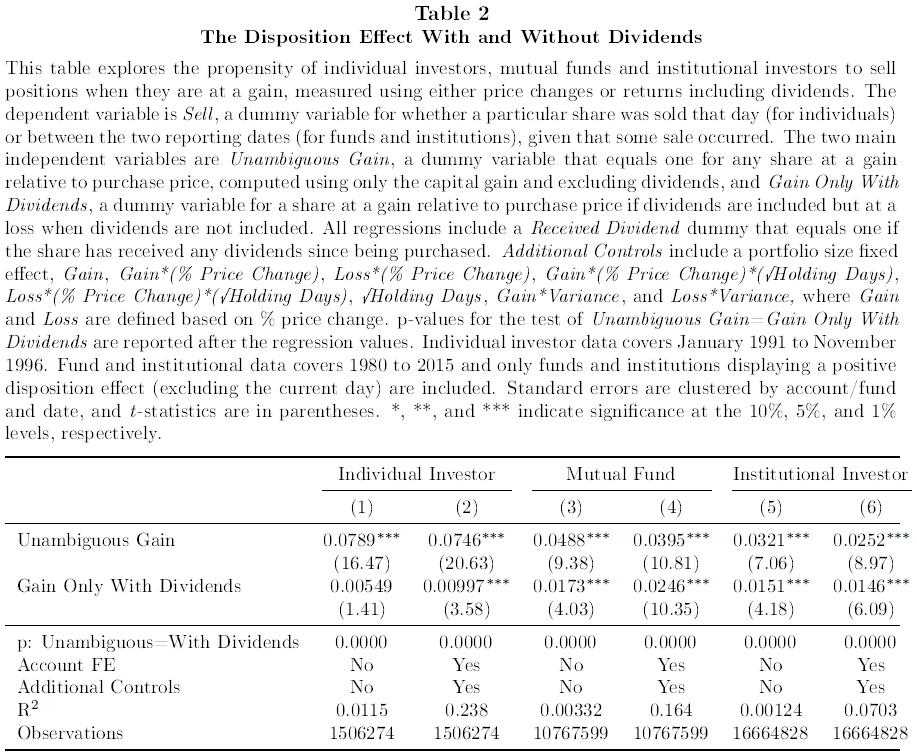

The results are found in Table 2. As shown in Columns 1 and 2, the authors find that individuals are around 7.5% more likely to sell a gain as opposed to a loss, also known as the disposition effect. Examining the “Gain only with Dividends” variable, the authors find that individuals sell winners based only on total return of the position (around 1% more likely to sell unambiguous gains compared to unambiguous losses in Column 2); however, this rate of selling winners on a total return basis (~1%) is much lower than the simple price appreciation assessment (~7.5%). The general results are similar for institutions and mutual funds who exhibit a positive disposition effect–stocks are more likely to be sold based on a simple price assessment compared to total return.(4)

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

The conclusion of Table 2 is best summarized by the authors:

Taken as a whole, the table suggests investors view the gain or loss status of a positions based on their price changes. Investors display a strong tendency to sell stocks that are at a gain using only price changes (the unambiguous gains case). However, stocks that are at a gain when dividends are included, but at a loss if dividends are excluded, are sold at a rate more similar to other positions at a loss than other positions at a gain. This is consistent with the predictions from the disconnect between price changes and dividends.

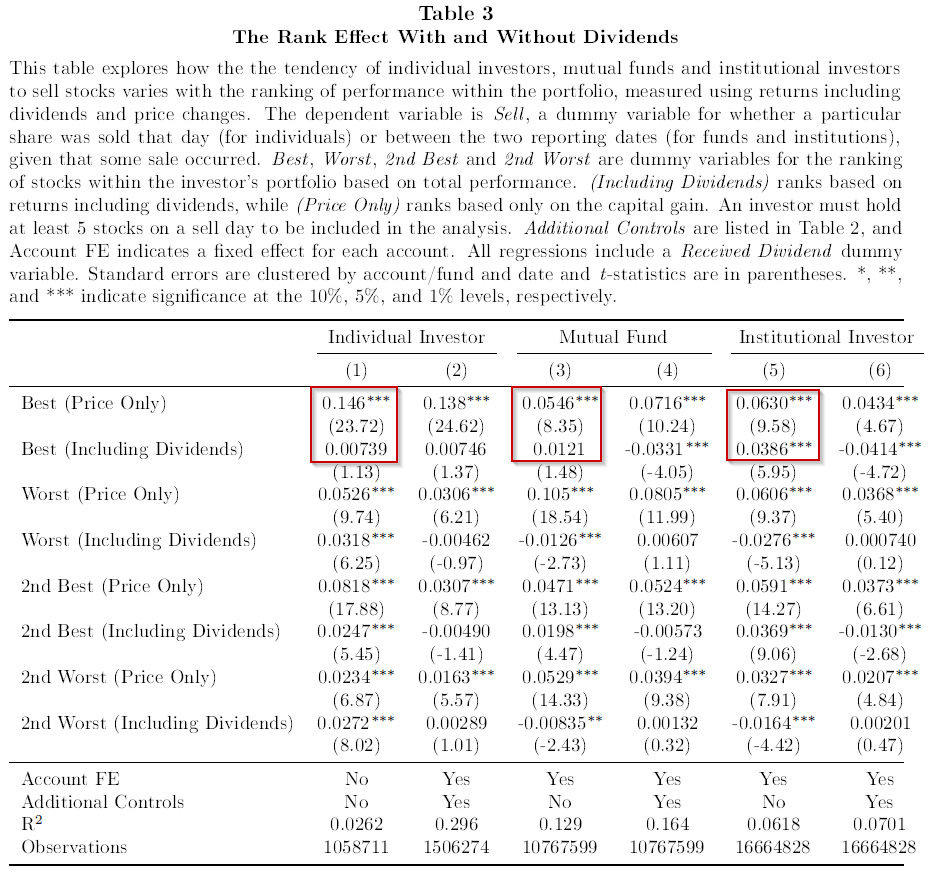

Table 3 finds a similar result, using another measure called the rank effect.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

The results are summarized:

For instance, the best-ranked position by price change is 14.6% more likely to be sold (with a t -statistic of 23.72), compared with the best-ranked position by returns including dividends which is 0.7% more likely to be sold (with a t -statistic of 1.13).

That is a crazy statistic and highlights the fact that investors appear to only assess the gain of a security on its price movement, not the total return.

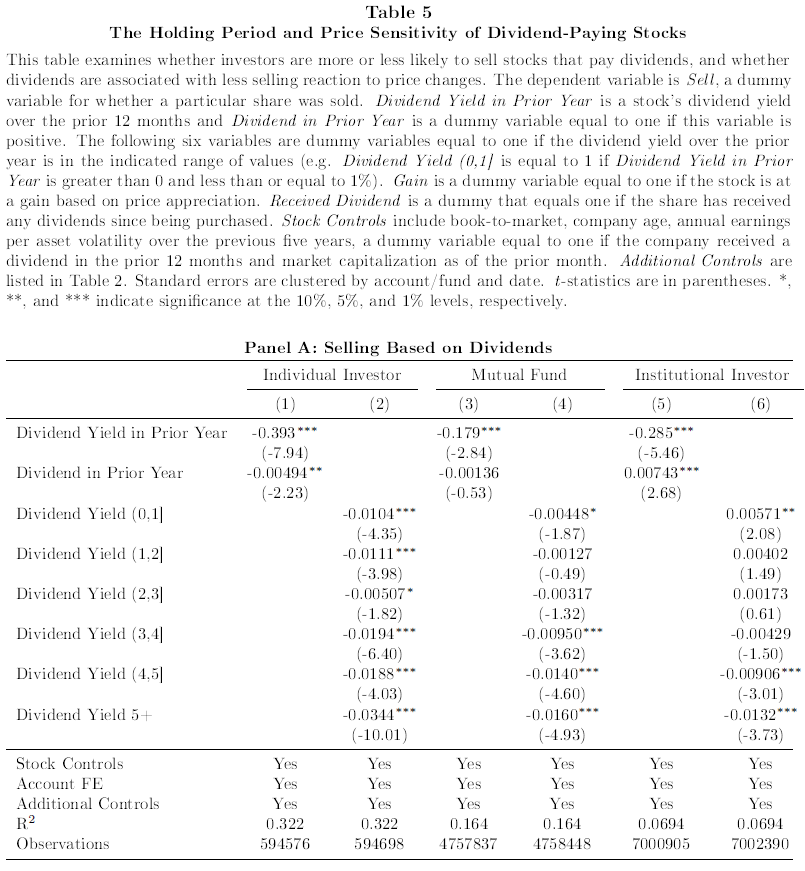

The paper then examines the second prediction — the Free Dividends Fallacy. The idea here is that investors assess dividend paying stocks differently than non-dividend paying stocks. From a mental accounting framework, the investors view the dividend payments as “free” and view a dividend-paying position as one with a (hopefully) perpetual payment of dividends. Under this mental accounting framework, one would expect non-dividend paying stocks to be assessed differently, since they don’t pay a stream of payments to the stockholder. This is examined in Table 5 of the paper.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

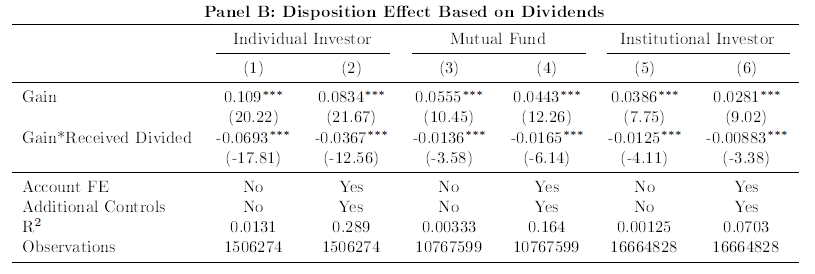

Across all investors, Table 5 (Panel A) highlights that investors are less likely to sell a stock as the dividend yield increases. Next, the authors ask the following question–does the propensity to sell a “winner” change if the stock is a dividend paying stock? The results are in Table 5, Panel B:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

In Panel B of Table 5, the authors regress a Sell dummy variable against (1) a Gain dummy variable and (2) an interaction variable of the Gain dummy variable and a Dividend received dummy variable. The interaction variable is used to test the free dividend hypothesis. The authors find that individuals, mutual funds, and institutions all have a lower propensity to sell a dividend paying stock that has a gain, relative to a non-dividend paying stock that has a gain.(5)

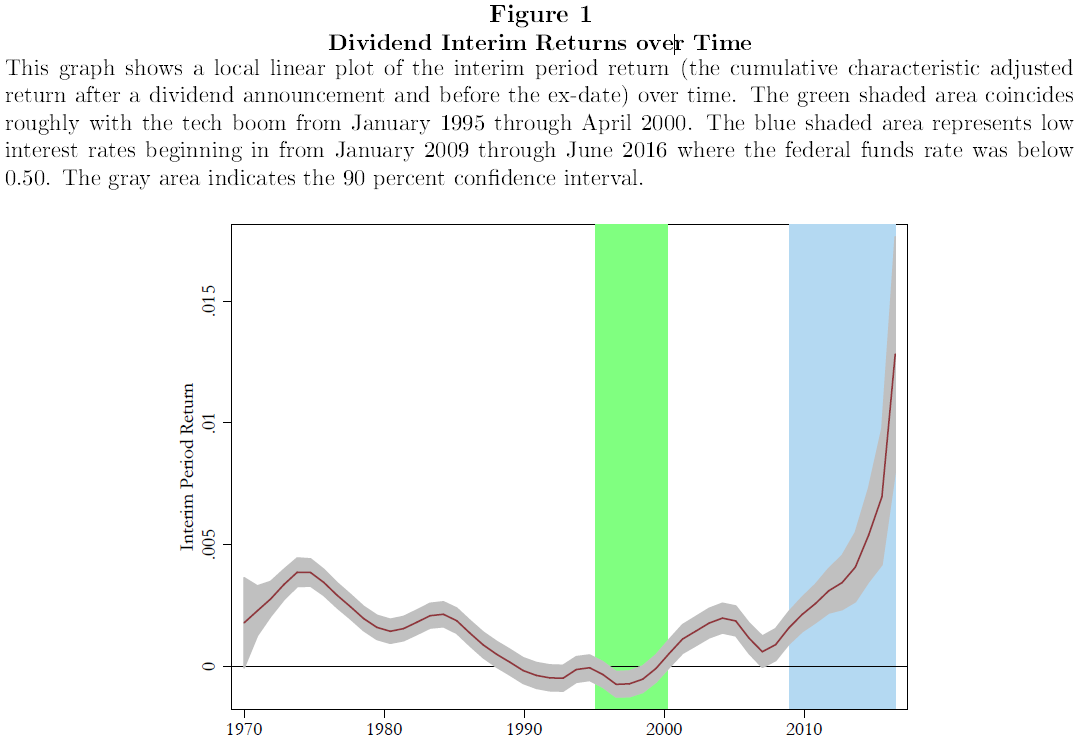

Thus, it appears that investors mental account–dividends and price changes are treated differently. Another way to validate this theory is to examine the “demand” for dividends over time. If investors are paying more attention to dividend payments, these may be more valuable in low interest rate environments. If investors are paying more attention to price appreciation, the demand for dividends may decrease. But how does one measure the “demand” for a dividend payment? One way is to examine the returns to dividend-paying stocks between the announcement date and the ex-data.(6) An investor demanding a dividend payment would, all else equal, buy a dividend paying stock after the announcement date. If there is a high demand for dividends, buying pressure may increase the characteristic-adjusted return (during the period after the announcement date and before the ex-date) for dividend paying stocks in time periods when demands for dividends are higher. Figure 1 below shows the return to dividend-paying stocks (with characteristic adjustments) between the announcement date and the ex-date.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

What one notices in the figure above is that (on average) the returns to dividend-paying stocks are positive between the announcement date and the ex-date, with the exception being the tech boom in the late 1990s.(7) More recently (the blue-shaded area of the chart highlights that while interest rates have been lower, the returns for dividend-paying stocks between the announcement date and ex-date are very

positive — indicating investors’ demand for dividend-paying stocks may be greater in a lower interest rate environment. The authors test and find this result in Table 7 of the paper.

However, the real question is that at the end of the day, does this mental accounting affect investor returns? There are a few effects highlighted in the paper.

First, and most obvious, are taxes:

The free dividend fallacy has a number of costs to investors. The most direct cost is the tax effect of receiving dividends versus selling the equivalent number of shares. For taxable investors, dividends will generally have tax consequences, whereas selling shares only results in capital gains tax if the position was sold at a gain, in which case only the capital gains portion of the sale is taxed. As a result, dividends are likely to be worse on average for tax purposes. If an investor has a need for a certain amount of money, receiving it in the form of a dividend lets him benefit by avoiding trading costs associated with selling shares. Alternatively, if an investor would have kept the value of a dividend in his portfolio without the dividend, but does not reinvest it when he receives the dividend, he loses out on the future expected returns.

Second, future expected returns may decrease:

Specifically, demand for dividends by investors is not randomly distributed across periods, but instead investors systematically demand dividends at the same time. To the extent that book-to-market ratio of dividend-paying stocks decreases in times of high dividend demand, and this book-to-market ratio can be interpreted as a stock being relatively over- or under-priced, the analysis suggests that in periods of high dividend demand, dividend stocks are likely to pay lower returns in the future. To understand the magnitude of this cost we conduct a simple, back-of-the envelope calculation. Our predictor of future mispricing is the average book-to-market ratio of dividend-paying firms in a given month, divided by the average of non-dividend-paying firms. Our measure of future returns is the average cumulative return over the next 12 months of dividend-paying firms minus the same average for non-dividend-paying firms. We regress this return gap on the difference in book-to-market ratios between dividend-paying and non-dividend-paying firms. We find a coefficient of 0.225 with a t -statistic of 2.16 (with Newey West standard errors with a 12 month lag). The interpretation is that the difference in book-to-market ratio of dividend-paying stocks to non-dividend-paying stocks predicts the future return gap between these two types of firms. In other words, when dividend-paying firms are relatively highly valued compared to other firms, they also have relatively lower future returns.

So it appears mental accounting may end up in lower returns for investors.

Last, the paper examines and tests the third prediction — Capital gains and dividends are spent differently. The results are found in Tables 9 and 10, and highlight the dividend reinvestment policy of mutual funds and institutions.(8)

Conclusion

In conclusion — this paper adds to the ever growing literature highlighting that human psychology impacts investment decisions!

Specifically, investors (1) disconnect capital appreciation and dividends when making decisions and (2) appear to suffer from a “free-dividend” fallacy. We recommend any interested to read the entire paper.

Please let us know what you think!

The Dividend Disconnect

- Samuel M. Hartzmark and David H. Solomon

- Paper

Abstract

We show that many individual investors, mutual funds and institutions trade as if dividends and capital gains are separate disconnected attributes, not fully appreciating that dividends come at the expense of price decreases. Behavioral trading patterns (e.g. the disposition effect) are driven by price changes excluding dividends. Investors treat dividends as a separate stable income stream, holding high dividend-yield stocks longer and displaying less sensitivity to their price changes. We term this mistake the free dividends fallacy. Demand for dividends is systematically higher in periods of low interest rates and poor market performance, leading to high valuations and lower future returns for dividend-paying stocks. Investors rarely reinvest dividends into the stocks from which they came, instead purchasing other stocks. This creates predictable marketwide price increases on days of large aggregate dividend payouts, concentrated in stocks not paying dividends.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Here are some behavioral biases investors exhibit. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The paper has three predictions, but I chose to focus on the first two predictions. I mention the third prediction below–please read the entire paper if you are interested! |

| ↑3 | Hence the title of the paper — “Dividend Disconnect” |

| ↑4 | The authors note there is actually a negative disposition effect for institutions and mutual funds in the online appendix. The analysis in Table 2 only examines those institutions and mutual funds that exhibit a positive disposition effect ~40% of the sample |

| ↑5 | This is shown through the negative a significant loading on the interaction term in the regression |

| ↑6 | Note a new paper uses Google searches to track investor demand for dividends. |

| ↑7 | During a time period when (some) investors were focusing on high-flying tech stocks |

| ↑8 | For more information on this section, please read the paper! |

About the Author: Jack Vogel, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.