Quantitative investing has developed an unjustified PR problem based on the unfortunate tendency of many to associate all quantitative approaches with “Black Box” investing.

The problem with a black box is that you don’t know what’s inside it, because by definition it’s opaque and non-transparent. You don’t know how it works. You put X in on one side, and Y comes out the other, but you don’t know how confident you should be that Y will resemble your expectations for the box’s output. For this reason, Black Boxes are a dangerous place to invest capital.

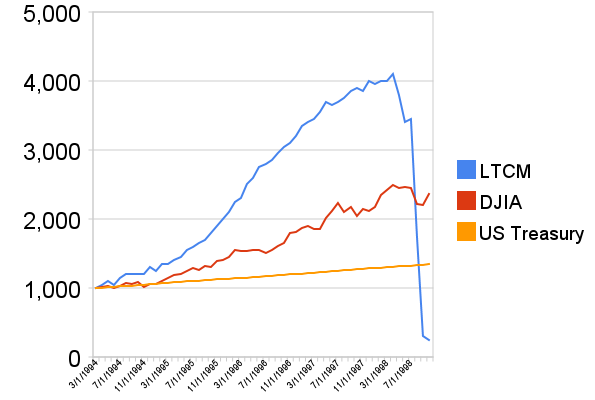

A famous example of Black Box investing is Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). LTCM was a hedge fund, run by Nobel Prize winners, and used leveraged “market-neutral” strategies that initially generated returns in the 40% range. The chart below tells you all you need know about how things ended for this Black Box:

Yet LTCM had good reasons not to be transparent about what they were doing. They wanted to guard their “secret sauce” and preserve a reputation that they were doing something unique. They didn’t want other firms to know their positions, which could jeopardize their ability to unwind them. They didn’t want to hear opinions about how much risk they were taking. As it turns out, all these reasons came back to bite them.

LTCM initially pursued bond arbitrage strategies, but then grew hungry for ways to continue making high returns with more capital. They pursued pairs-related “convergence” trades. They made bets in merger arbitrage. They explored technically driven approaches, involving trend analysis and pattern recognition. In the end, they were not doing something unique, they could not unwind their positions, and they were taking too much risk.

With high profile outcomes like LTCM, it is no wonder that that investing based on an “algorithm” has developed negative connotations. But we think it’s unfair to lump all quantitative investing in with such Black Boxes.

There are alternative common sense approaches to quantitative investing that don’t involve whiz-bang mathematics that are long on ego-production, but short on robustness.

Enter the original common sense quant

Consider Ben Graham, the father of value investing. He advocated that investors seek a margin of safety by buying securities only when they are cheap:

The buyer of bargain issues places particular emphasis on the ability of the investment to withstand adverse developments. For in most such cases he has no real enthusiasm about the company’s prospects. True, if the prospects are definitely bad the investor will prefer to avoid the security no matter how low the price. But the field of undervalued issues is drawn from the many concerns—perhaps a majority of the total—for which the future appears neither distinctly promising nor distinctly unpromising. If these are bought on a bargain basis, even a moderate decline in the earning power need not prevent the investment from showing satisfactory results. The margin of safety will then have served its proper purpose.

There is no Black Box here. The logic is clear and transparent. This is a common sense approach, based on practical investment knowledge. Or consider the following quote from Warren Buffett:

If you buy a dollar bill for 60 cents, it’s riskier than if you buy a dollar bill for 40 cents, but the expectation of reward is greater in the latter case. The greater the potential for reward in the value portfolio, the less risk there is.

Again, there are no Black Boxes here. The message is simple, and very similar to what we heard from Ben Graham above, and can be summed up in two words: buy cheap.

We believe that you can apply this simple, time-tested strategy of always buying cheap stocks, but use the power of the computer to leverage your ability to search the universe of publicly traded securities for those that are the cheapest. You can argue about whether this is a sound strategy, but we think any such arguments should be about the value investing approach itself rather than the use of computers.

As Seth Klarman has observed:

Warren Buffett once wrote that value investing is ‘like an inoculation–it either takes or it doesn’t,’ and when you explain to somebody what it is and how it works and why it works and show them the returns, either they get it or they don’t.

The use of computers should not fundamentally invalidate the value investing approach. We can understand if you fundamentally disagree with the value investing philosophy. That is a disagreement on philosophy and the interpretation of the empirical results. If value investing isn’t sensible to you, then invest using some other approach. But one thing you should not do, is avoid quantitative techniques and tools on the grounds that they are too “Black Box.”

About the Author: David Foulke

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.