Consider the financial challenges faced by the average endowment. The endowment seeks to grow its asset base over time, but is called upon to divert a steady, predictable cash flow stream from the portfolio to finance the operations of the institution. Thus, in addition to its mission of growing its assets, it must also be highly sensitive to the risk of significant capital impairment. If the portfolio suffers a large drawdown, then it risks putting its operating plans in jeopardy. The best endowment managers, such as Yale’s David Swenson, manage this balancing act well, consistently growing the asset base, while ensuring that the ongoing cash flow requirements of the institution can be met without compromising the portfolio, no matter the prevailing market conditions. This is accomplished by careful management of the underlying allocations within the portfolio.

“Fine,” you say. “This all sounds reasonable. But how am I supposed to determine the appropriate weightings to begin with, and then how do I rebalance these various asset classes going forward?” Anyone who has sat through the obligatory business school finance classes covering the capital asset pricing model may have some recollections of how one might approach this allocation conundrum, since the theoretical imperative was hammered relentlessly into their heads. According to most b-school professors, holding the market-weighted portfolio of all assets is the way to go. If you don’t like a ton of risk, simply hold the market portfolio and pair it with some risk-free bond exposure. This all works if you assume investors only care about average returns and standard deviation, you throw in a little Markowitz mean variance mathematics and some assumptions on investor rationality. The tactical asset allocation rule is clear: investors should seek a value-weighted portfolio of all assets in all markets in the economy. It is no surprise, therefore, that this is what you hear when you sit in the classroom at business schools today.

Yet is it possible there is another way? After all, ideally, as financial conditions change, and asset classes within a portfolio fluctuate, investors might hope to tactically reallocate to take advantage of, say, a distressed situation in an asset class that has recently been hammered. The successful tactical asset allocator might thereby seek to derive a benefit from changes in the underlying market environment. But how might you begin to attempt such an outlandish approach that flies in the face of the accepted market orthodoxy?

And that, dear reader, is where Turnkey Analyst comes in, as we have been hard at work researching this very question. It turns out there has been a sizable body of research over the past several years into how one might hope to make such judgments. What we are looking for is an approach that will dynamically position us, over weighting us in those asset classes that offer the potential for significant gain, while simultaneously de-emphasizing those that are likely to generate losses. Is the process perfect? Of course not. Will they definitely work in the future? Who knows. But one thing is certainly clear: holding the “market portfolio” is a sure way to eat 50% drawdowns for breakfast.

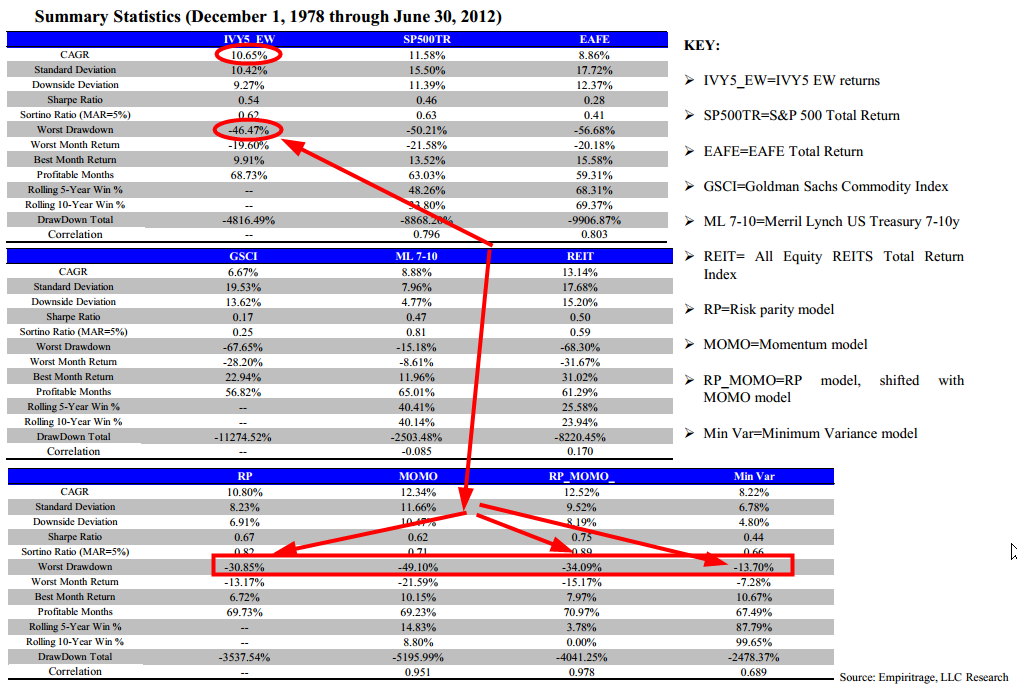

Below are some backtest performance results achieved by applying different tactical asset allocation models. As you can see, the choice of model can have a significant influence on the outcome.

[Click to enlarge] The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

The simple buy-and-hold equal-weight index eats a 47% drawdown. Yuck. Meanwhile, simple risk parity models, minimum variance allocations, or risk parity and momentum combinations drop the drawdown to 30% or less. If one adds a long-term MA rule on there, the results are even better.

As you can see from the data above, it would appear that different approaches to tactical asset allocation can have dramatically different outcomes. We believe it is possible to use signals supplied to us by the markets to inform our exposures to different asset classes. If you are curious and want to learn more about some of the cutting edge research exploring these tantalizing areas within finance, then stick with Turnkey Analyst. We will share all our insights and then you can judge for yourself.

Big question: If this is so “easy,” why isn’t everyone doing it?

A few possibilities:

- Data-mining–maybe the results were a result of good luck and the next 30 years won’t be so kind to the tactical asset allocation models suggested

- Institutional Structure–Imagine a manager of a large endowment telling his investment board that he’ll be dropping stock exposure to zero because a long-term MA rule was triggered? Good luck with that.

- Model Discipline–Most people simply can’t stay discipline to a systematic strategy. Why? Unclear, but my guess is it is the same reason people love eating Bic Macs, skip exercise, and can’t save for retirement.

About the Author: David Foulke

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.