Running a marathon is similar to being a value investor, especially in recent years where it seems more like an ultra-marathon. Both activities are painful experiences that require the ability to suffer and persist through physically and emotionally straining times. Moreover, value investors always need to worry about the perennial “dogs” in their portfolio, which are stocks that are cheap and stay cheap. For example, the novice value investor may stumble across an incredible bargain stock — a price-to-earnings ratio below 10, what’s not to like?

However, after years of holding such stocks without much performance to show for, the realization sets in that these cheap stocks reflect structurally impaired businesses. The stock is not mispriced and market expectations are not wrong, it is simply a dying business that is on the way to bankruptcy. Another name for these stocks is “value traps.”

How can the systematic value investor minimize the chance of a value trap? Investors have several tools at hand to avoid these siren stocks and one common approach is to rank cheap stocks by another metric, effectively creating a multi-factor portfolio. Ideally, these other factors feature low or negative correlations to Value, where Momentum and Quality represent the most popular choices.

In this short research note, we will contrast Value & High Quality (our favored style) versus Value & Low Quality across stock markets. (Please note that the Quantitative Value Index, which was developed by Alpha Architect, specifically seeks to leverage quality metrics to improve a generic systematic value strategy. You can read more about that here. My piece is related to this concept but I approach it in a simple way to make a basic point about the potential benefits of incorporating quality into a value strategy)

Good Versus Bad Value Stocks

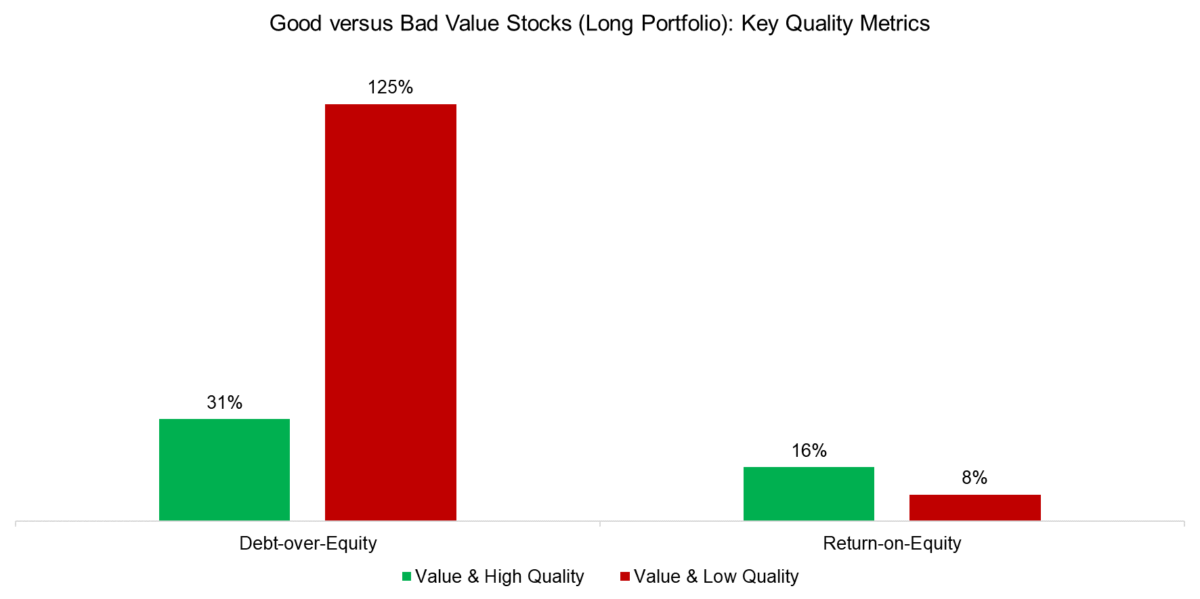

We focus on all stocks in the US, Europe, and Japan with a market capitalization larger than $1 billion. We utilize a sequential model to first rank all stocks by value using an equal-weight combination of price-to-book and price-to-earnings multiples and then rank the residual universe by quality using a combination of debt-over-equity and return-on-equity ratios. At each step, 30% of the stocks are selected, which results in concentrated portfolios on the long and short side. Given that we rank for high and low quality, this approach generates four portfolios: cheap and high quality, cheap and low quality, expensive and high quality, and expensive and low quality.

We can highlight the fundamental differences by contrasting the long portfolio of the multi-factor combinations, which shows a lower debt-over-equity and a higher return-on-equity ratio for the cheap and high-quality stocks, as per definition.

Good and Bad Value Stock Valuations

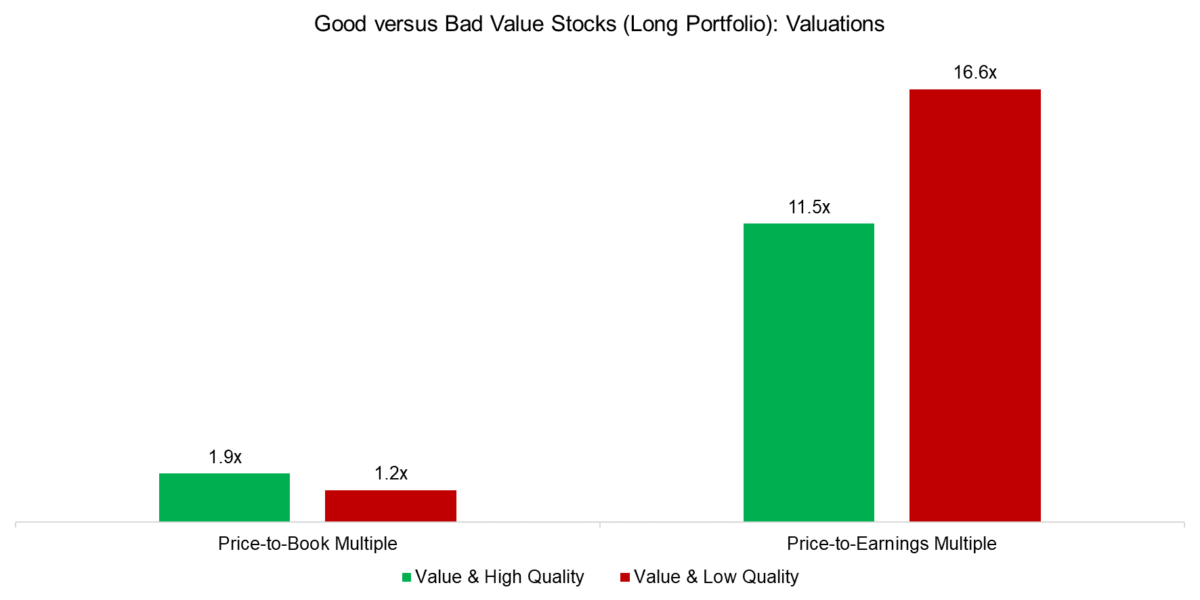

Intuitively, cheap and low-quality stocks should be cheaper than cheap and high-quality stocks, which is the case when using median price-to-book multiples, but not for price-to-earnings (PE).

It is somewhat unusual to observe that investors seem to pay higher PE multiples for companies with worse fundamentals, however, this can be explained by different sector biases. Both portfolios are heavily exposed to financials, but the portfolio comprised of cheap and low-quality stocks has an almost 30% allocation to real estate and utility stocks, which represent highly leveraged companies that tend to trade at above-average PE multiples.

A Return Comparison

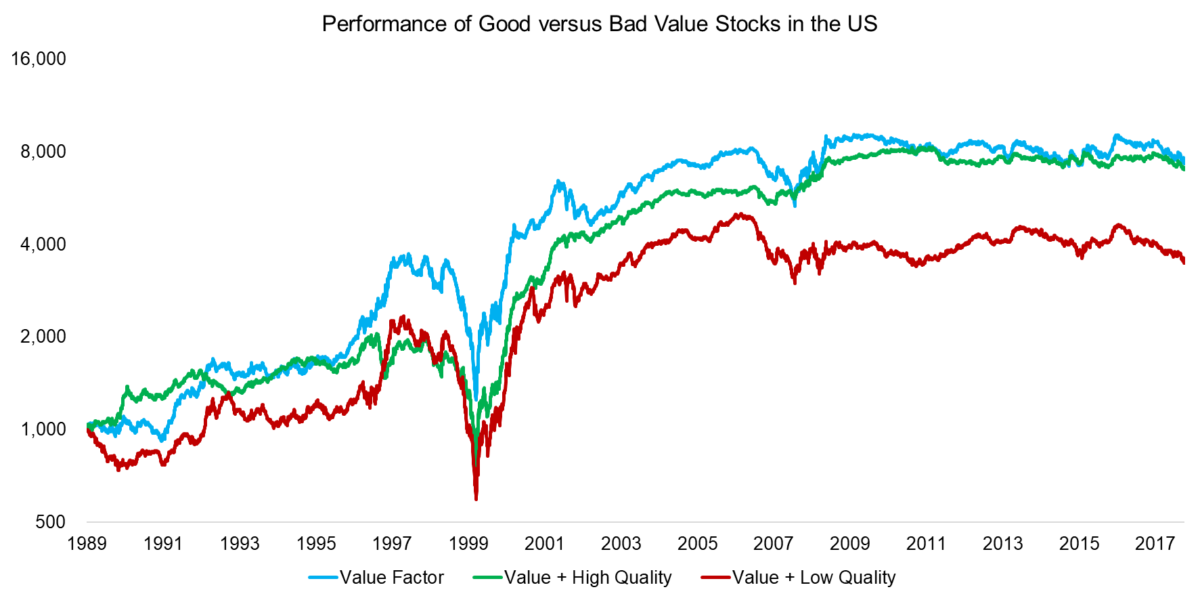

Theoretically, value traps should be detracting from the performance of the value factor, therefore excluding these should result in better returns. However, the performance of the long-short value factor and the value & high-quality combination in the US were approximately the same in the period between 1989 and 2018. (results are different, internationally).

The value & low quality portfolio performed worse than the factor on a stand-alone basis, as expected, but it seems that the cheap stocks with average-quality characteristics outperformed those with high-quality features.

Avoiding Value Traps Across Markets

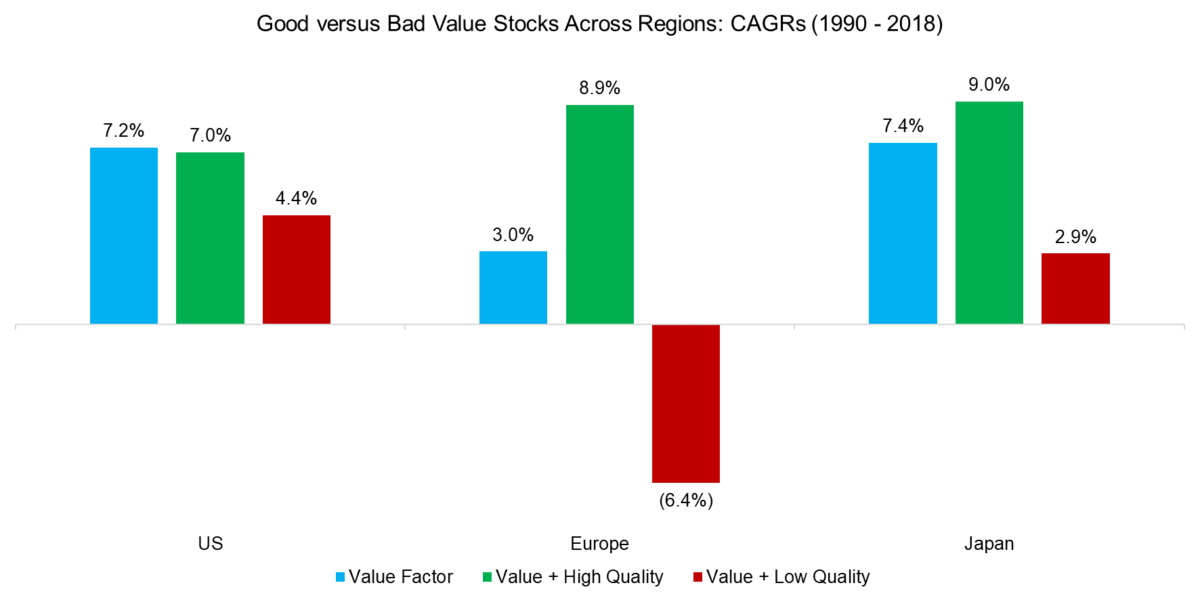

Next, we calculate the CAGRs for the three scenarios in the US, Europe, and Japan, which highlights positive excess returns from the value factor across regions over the last three decades. Naturally, these returns were not distributed equally and were largely negative over the last decade, but that is another discussion.

However, more interestingly, we observe that in Europe and Japan the value & high-quality combination significantly outperformed the value factor. It is difficult to explain why this approach was less successful in the U.S., but should not be regarded too critically as financial markets are noisy. The threshold for quantitative approaches to be of interest is that a methodology should have a sound economic foundation and should work on average, but not necessarily in each market or over too short time periods.

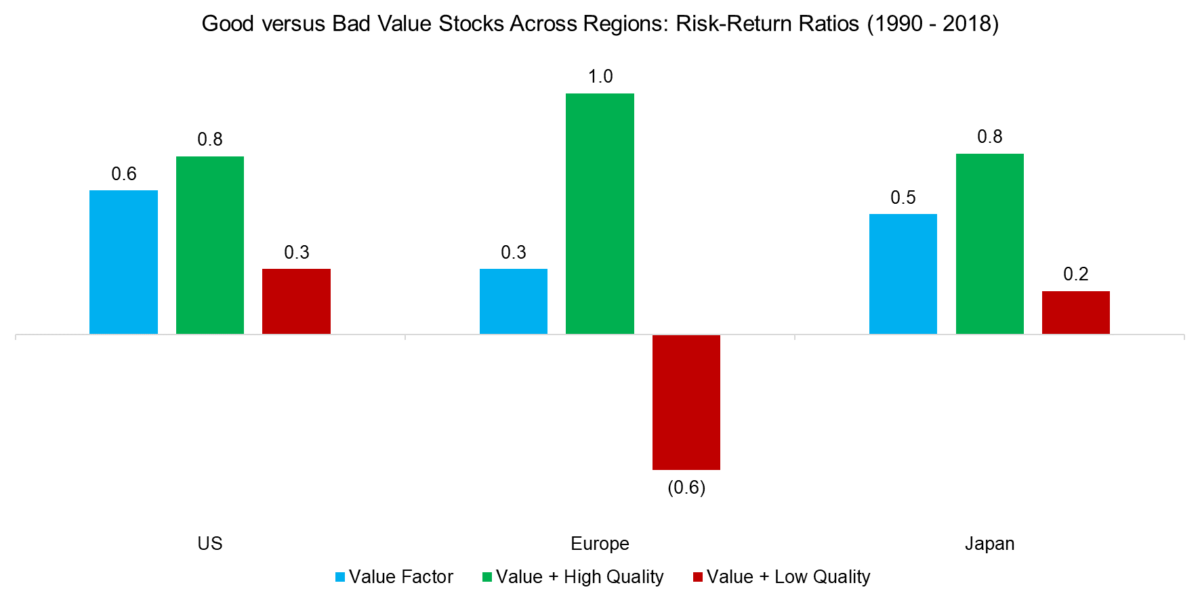

Finally, we calculate the risk-adjusted returns for the three scenarios, which shows that focusing value & high quality resulted in the highest risk-return ratios across markets. Given that the return for the factor combination was lower than for the value factor in the US implies lower volatility when including quality metrics, which is intuitive. Cheap stocks tend to be companies in trouble, but when leverage is low and profitability moderate, then it might be more temporary than structural issues.

It is also worth noting that the value & high-quality combination experienced much lower maximum drawdowns than cheap stocks. In the US the maximum drawdown, which occurred during the tech bubble in 1999, only reduced from 66% to 63%, but from 65% to 46% in Europe, and from 83% to 34% in Japan.

Further Thoughts on Incorporating Quality into a Value Strategy

Factor investing is like cooking. There are millions of plants, but only a few are edible and relevant for our kitchen. Some like potatoes or rice can be eaten as a stand-alone meal, but result in a rather bland eating experience. Mixing these up with herbs and spices produces a much more delicious and balanced dish.

Quality on its own is not an attractive factor as it is difficult to make a case that investors should be earning positive excess returns for holding stocks featuring low leverage and high profitability. The factor is more useful as a filter, similar to the Size factor, although that is currently being hotly debated in otherwise calm academic circles.

However, even if focusing on high-quality cheap stocks has generated more attractive returns than cheap stocks on their own, the performance still largely represents that of the Value factor. No amount of herbs or spices will cover that up.

Related Research

How Alpha Architect Builds a Value and High Quality Portfolio

The recipe and reason for adding Momentum and Value

About the Author: Nicolas Rabener

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.