Prospect theory was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. The theory starts with the concept of loss aversion—the observation that people react differently between potential losses and potential gains. Thus, people make decisions based on the potential gain or loss relative to their specific situation rather than in absolute terms. Faced with a risky choice leading to gains, individuals are risk averse, preferring solutions that lead to a lower expected utility but with a higher certainty (concave value function). On the other hand, faced with a risky choice leading to losses, individuals are risk-seeking, preferring solutions that lead to a lower expected utility as long as it has the potential to avoid losses (convex value function). These examples contradict expected utility theory, which only considers choices with the maximum utility.

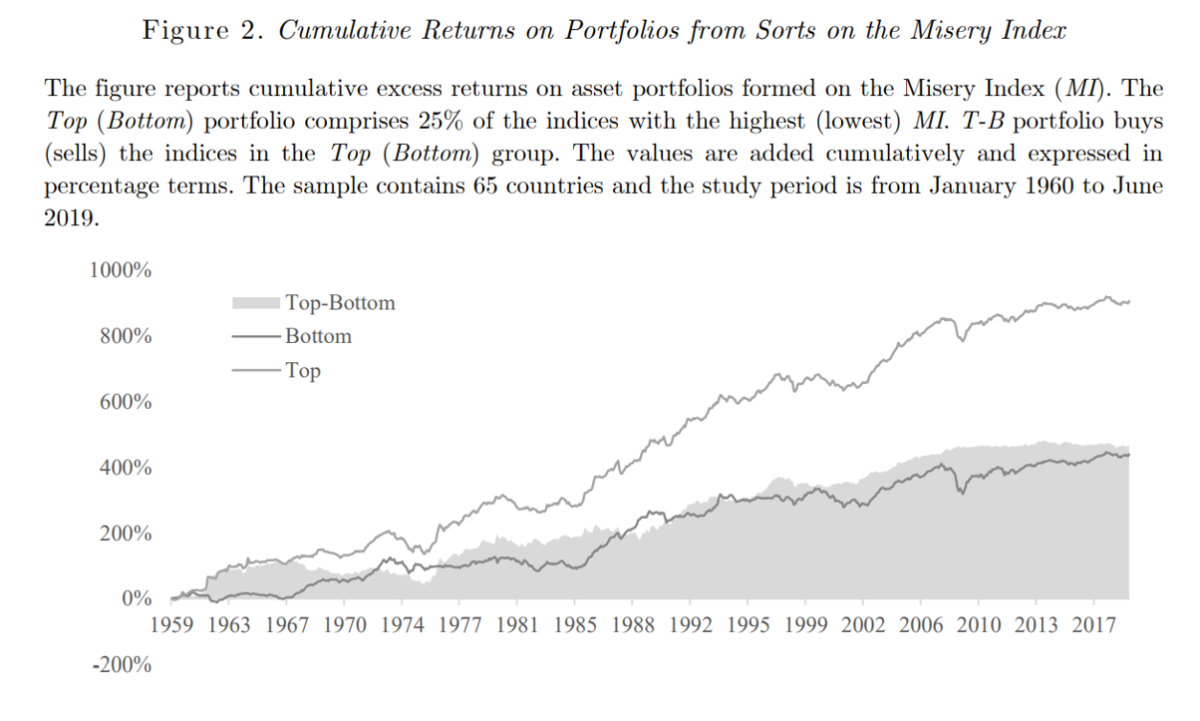

Nusret Cakici and Adam Zaremba, authors of the December 2020 study “Misery on Main Street, Victory on Wall Street: Economic Discomfort and the Cross-Section of Global Stock Returns,” examined how local economic discomfort influences investors’ risk aversion, leading to a cross-sectional variation of equity risk premia around the world. Based on prospect theory, their hypothesis was that the greater the local economic discomfort, the greater the risk aversion investors would exhibit. That would cause investors to demand a greater equity risk premium, leading to higher future returns. They used the well-known misery index (MI), which adds the unemployment rate to the inflation rate, as their indicator of economic discomfort. Their data was from 65 stock markets (23 developed markets and 42 emerging markets) for the years 1960-2019. Returns were benchmarked against the single-factor (beta) capital asset pricing model (CAPM), the three-factor (beta, size and value) model, and an eight-factor model: market, value, momentum, long-run reversal, idiosyncratic risk, beta, skewness and seasonality. To avoid any look-ahead bias, the data was lagged by four months. All returns were measured in U.S. dollars.

Following is a summary of their findings:

- Economic discomfort reliably predicts future equity returns, with both components (inflation and unemployment) adding explanatory power.

- The quartile of countries with the highest MI outperformed the countries with the lowest MI by 0.65 percent per month (t-stat = 3.8), and the associated long-short portfolio produced an eight-factor model alpha of 0.40 percent per month. Importantly, the different portfolios from sorts on MI displayed comparable levels of return standard deviation—the return variation does not appear to be a compensation for volatility.

- The effect of the MI signal is not short-lived but rather relatively persistent through time. Even if the long-short strategies were reformed and rebalanced once every 12 months, the top MI markets continued to perform better than the bottom MI markets.

- The phenomenon is not subsumed by a battery of established return predictors. For example, the eight factors only explained about 15 percent of the overall time-series variation in MI long-short strategy returns.

- The effect is stronger in smaller and less developed countries, where prices are set primarily by local investors and where uncertainty avoidance is high. In large, developed, and open economies, where the role of local investors is smaller and the prices are at least partly dictated by international investors, the role of MI is smaller.

- The MI effect is stronger among markets of high earnings yield (E/P ratio) and small capitalization.

- The role of MI is much stronger in closed economies (the eight-factor alpha was 0.90 percent) than in open economies (the eight-factor alpha was 0.07 percent).

- The return predictability does not deteriorate through time, as frequently happens with behavioral anomalies due to investor learning—the MI effect is not a manifestation of mispricing but reflects an economic risk premium.

- The composition of both sides was substantially diversified, and as many as 46 to 54 (56 to 57) countries were included in the low MI (high MI) portfolios for at least a month—the vast majority of countries go through long and short MI portfolios at some point in time.

- The economic discomfort premium can be successfully harvested with liquid, long-only exchange-traded funds, and turnover is not excessive (comparable with country-level value and quality strategies).

Their findings provide an important takeaway for investors: When risk aversion levels are highest, future expected equity returns are also highest! Thus, it is not a good time to engage in panicked selling. While it may seem logical to sell stocks when the economic news (the misery index) is bad and wait for the economic news to get better, those with a knowledge of financial history know that would likely turn out to be a mistake because the economy and the market are two very different things. (see here for an example: “Turn off your chief economist”). The economic news is backward-looking, reporting on what has already happened. On the other hand, the market is always forward-looking, anticipating that the worse the economic news, the more likely it is that central banks (monetary policy) and governments (fiscal policy) will take counter-cyclical measures to turn things around.

Sophisticated investors also know the markets are highly efficient at incorporating all known information into current prices. One result is that there is a big difference between information and value-relevant information. In other words, if you are aware of the bad news, surely all the large institutional investors that dominate trading and therefore set prices are also aware. Thus, the scary information that has you worried is already incorporated into prices. It is not that the stock market will go lower because of the bad news, but rather that the market is where it is because of the bad news—if things were not this bad, prices would be higher.

With this understanding, we know that it is unexpected events (which, by definition, are unpredictable) that are the major factors driving future stock prices. Thus, it doesn’t matter whether future news is good or bad; what matters is whether it is better or worse than already expected. And we also know that central banks and governments do not just sit idly by watching their economies collapse. Instead, they take actions to address the problems, using stimulative monetary and fiscal policies to help turn the economy around. Because the market is forward-looking, it tends to recover well before the economy does. That is exactly why it is one of the leading indicators used by economists to predict economic recoveries. The bottom line is that a weak economy does not predict a bear market. And as Cakici and Zaremba demonstrated, when the misery index is high, expected returns are also high.

Important Disclosures

The information presented herein is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is based on third party data and maybe become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Third party information is deemed to be reliable but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Strategic Wealth® / Buckingham Strategic Partners® (collectively Buckingham Wealth Partners) R-21-1678

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.