If you love a good Goldman Sachs conspiracy theory, we’ve got a candidate for you…

Our story begins back in 2003, when the Fed allowed regulated banks to trade physical commodities, unleashing a decade of increased bank activity and revenues in the commodity sector. Goldman was considered a top commodity bank, and grew commodity revenues to over $3 billion by 2007.

At this time, the fact that banks were investing in physical commodities was fairly uncontroversial. That all changed during the financial crisis, when the Fed converted Goldman into a bank holding company, and began regulating its commodity trading. Goldman and other banks were given 5-years to divest their non-financial businesses, although it was unclear exactly what that meant for Goldman’s commodity business, which many argued was complementary to, and thus technically part of, its financial activities.

After the global recession, with the Fed keeping rates low, banks were pressured to get creative in their search for higher yields. Goldman, as usual, was particularly creative. In 2010 Goldman paid $550 million to acquire Metro International Trade Services, which managed a number of warehouses approved by the London Metal Exchange to settle physical commodity trades in aluminum.

With the Metro International acquisition, Goldman began participating in physical storage as part of its commodities business. Warehouses are an important node in commodity trading since, unlike in the financial markets, trades can be settled with delivery, which gives warehouses an important role as collateral manager. What went largely unreported in the financial press at the time, was that these warehouses made up some 80% of the storage space in the Detroit area, giving Goldman a near monopoly on regional aluminum storage.

There are several ways to make money with a warehouse. One way is to take advantage of “contango” market conditions, when futures prices exceed the spot price. One popular trade is the carry trade, or “warehouse trade.”

It works like this: A trader uses borrowed money and buys aluminum directly from a producer or the physical market, and puts it into a warehouse. Then the trader sells a higher priced aluminum future, locking in profits, and when the contract expires, the trader settles the contract by delivering the underlying asset.

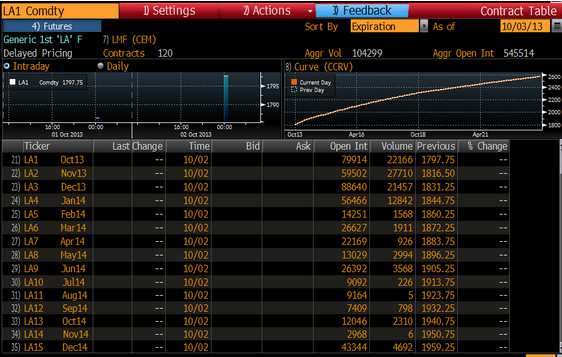

For an idea of how it might work in today’s aluminum market, take a look at the futures prices for a ton of aluminum:

Let’s say you are a trader, and you buy physical aluminum today for $1,798, and hedge by selling the October 2014 future for $1,940. You have a: $1,940 – $1,798 = $142 spread to apply towards warehouse rental, handling, and financing charges. If these charges are less than $142, you are earning arbitrage profits. Contango market conditions, like the ones seen above where the futures price is higher than the spot price, can make it compelling for a bank such as Goldman, and its extremely low financing and storage costs, to pursue this trade. And the trade appears to have been profitable for Goldman, as it began to offer producers significant premiums over the spot price in order to bring additional aluminum supplies into its warehouses.

All well and good for making money on the warehouse trade, but then a change occurred. Delivery times – the time required to physically remove aluminum from the warehouses with forklifts to get it to market – went from a reported 6 weeks in 2010, to as long as 16 months in 2013…

This changed the economics of the warehouse trade.

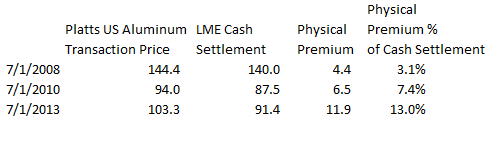

Within commodity markets, there is often a premium associated with physical versus cash settlement. This may reflect regional logistics anomalies, such as a freight charge from a remote market, or local supply/demand imbalances. In cases when delivery logistics become clogged, it might also include a premium for prompt delivery. Take a look at recent trends in the yield spread (in cents/lb) between the physical and the cash market in aluminum:

Note how the premium increased from 3% of the cash settlement price in 2008 to 13% in 2013. One interpretation of this trend is that the waiting times began to wreak havoc on the aluminum price discovery process, contributing to a disconnect between the physical commodity and financial instruments. In commodities, the “cash” market normally describes the market for immediate or near-immediate settlement. At some point the market ceases to be a cash market if you have to wait many months to get your underlying. Additionally, the physical premium is difficult to hedge. Large end-users such as Coca-Cola, Boeing and MillerCoors began to complain to the authorities. In the meantime, aluminum inventories in Goldman’s warehouses spiked, going from a reported 850,000 tons in 2010, to 1.5 million tons by 2013.

Recall from above, that the approximate difference between the one year aluminum future and the spot market is approximately $142 per ton. Let’s assume that Goldman gets paid this rental for its 1.5 million tons in inventory. This would equate to: 1.5 million * $142 = $214 million, which is a spectacular 39% cash on cash return on Goldman’s initial investment of $550 million in Metro International. Not bad.

We don’t have a dog in this fight, and there may be entirely reasonable explanations for the slowdown in deliveries and increase in the physical premium. You can make a case that strong contango conditions and low borrowing rates led to higher physical premiums, and warehouse logistics problems. The conspiracy theorists, however, believe that Goldman bought Metro International, established a near monopoly, and then intentionally slowed down its outbound logistics in order take advantage of higher physical delivery premiums, and build captive inventories for which they were paid additional rents, thereby boosting the IRR on the warehouse investment. We don’t know the truth, but regardless, it’s a great narrative.

One thing is clear, however, and that is that the Fed is taking a hard look not only at Goldman’s and other banks’ participation in ancillary commodity businesses like storage, but also directly at their involvement in commodity markets. As always, we look forward to seeing how it all plays out.

Thoughts?

About the Author: David Foulke

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.