Introduction to Finance: Class 6

Making Capital Investment Decisions

Where to begin?

Capital investment decisions also can be called ‘capital budgeting’ in financial terms. Capital investment decisions aim includes allotting the capital investment funds of the firm in the most effective manner to make sure that the returns are the best possible returns.

—Source

Capital Budgeting: Longer Overview Video

· · · · ·

Key Concepts:

- Relevant Cash Flows

- Estimating Project Cash Flows

- Evaluating Net Present Values Estimates

Relevant Cash Flows

- The cash flows that should be included in a capital budgeting analysis are those that will only occur if the project is accepted

- Cash flows that will occur regardless of whether or not we accept a project aren’t relevant (for our decision)

- Incremental cash flows

- Any and all changes in the firm’s future cash flows that are a direct consequence of taking the project

How to Identify Relevant Cash Flows

- You should always ask yourself “Will this cash flow change ONLY if we accept the project?”

- If the answer is “yes,” it should be included in the analysis because it is incremental

- If the answer is “no,” it should not be included in the analysis because it is not affected by the project

- If the answer is “part of it,” then we should include the part that occurs (or does not occur) because of the project

Sunk Costs

- Costs that occurred previously are irrelevant

- Example

- Duff Beer conducted a marketing survey 9 months ago to gauge the interest in introducing doughnut flavored beer. Duff today is deciding whether to produce the new flavor.

- Should Duff include the cost of the survey in its decision to launch its new product?

Opportunity Costs

- Something you give up to undertake the project

- Not always easy to identify

- Example:

- Pizza Bowl has been renting ½ of its building to a laundry mat for $30,000/year. Pizza Bowl is considering expanding the bowling alley to provide bowlers with more lanes and a larger food area.

- Should Pizza Bowl include this $30,000? How?

Externality Costs (Erosions/Synergies)

- Impact a project has on other activities of the firm

- Could be positive or negative

- Example:

- Tran’s Electronics wants to sell iPhones for the first time. They assume that iPhones will decrease sales of iPods by $15,000/year, but will increase the sales of head phones, cases, and iTunes gift cards by $6,500/year.

- What are the relevant cash flows?

- Are they synergies/erosions?

Example: Relevant Cash Flows

- Which of the following cash flows should be considered?

- General Milk hired a consultant to analyze the viability of an investment into a strawberry milk line. The consultant charges a fee for its analysis.

- You have started a home-based grocery delivery service and need to convert the room that you currently rent out at $400 per month into an office.

- You run a convenience store and are going to supplement your line of Coke products with Pepsi. The total demand for soda is presumed constant.

Stand-Alone Principle

- Each project can be evaluated in isolation once all relevant cash flows have been accounted for.

- Project can be viewed as a ‘mini-firm.’

Estimating Project Cash Flows

Capital Budgeting: Valuing a Capital Investment

- Interested in Cash Flow from Assets generated by Project

- Computing cash flows – walk down memory lane

- Operating Cash Flow (OCF) = EBIT + Depreciation – Taxes

- Cash Flow From Assets (CFFA) = OCF – Net Capital Spending (NCS) – Changes in NWC

- When evaluating a capital budgeting project, we must estimate the after-tax cash flows the asset is expected to generate in the future

- Future cash flows generally are uncertain to some degree, so the risk associated with a capital budgeting project should be considered

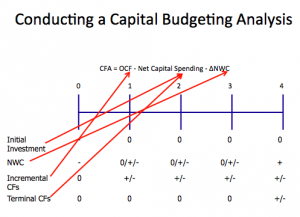

Conducting a Capital Budgeting Analysis

What does the “r” represent?

- Time value of money

- Riskiness of the cash flow derived from the project

- Required rates of return for the sources of funds, e.g., the long term debt holders and stockholders

Terminology

- Initial investment outlay—includes cash flows that occur only at the beginning of the project’s life.

- Changes in NWC—liquidity requirements for the project’s operation.

- Incremental operating cash flows—changes in cash flows that are sustained throughout the life of the asset.

- Terminal cash flow—the cash flows that occur only at the end of the life of the asset.

- Expansion projects—marginal cash flows include all cash flows associated with adding a new asset to grow the firm.

- Replacement analysis—marginal cash flows include changes (+ or -) in the cash flows associated with the new asset that replaces the cash flows associated with the old asset that is replaced (maintain existing operations by replacing an old asset).

Initial Investment Outlay

- Net Capital Spending portion of CFA

- Purchase Price

- Shipping and Installation

- Cost/Benefit of disposing of old asset

- Salvage Value

- Taxes

- Other “up-front” inflows/outflows

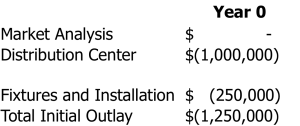

Dunder Mifflin is considering opening a Philadelphia branch for the next five years to augment its existing facilities in Scranton, PA.

After five years, they will close the Philadelphia branch and seek regional alternatives.

- A financial analyst has estimated the following costs:

- $100,000 market analysis (already conducted)

- $1,000,000 purchase of distribution center

- $250,0000 fixtures and installation of equipment

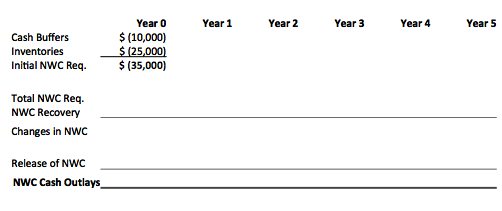

Changes in Net Working Capital

- Recall, change in net working capital

- Net working capital = CA – CL

- Includes:

- inventory levels

- cash buffers

- sales on credit

- purchase on credit

Example:

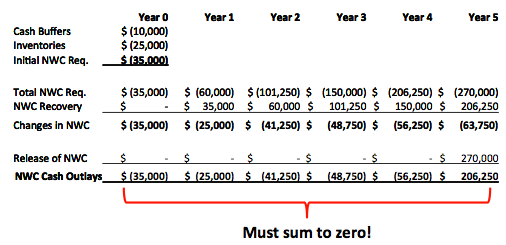

Michael Scott, head of the Scranton branch, estimates that the new branch will have the following working capital requirements:

- $10,000 in initial cash buffers

- $25,000 in initial inventories

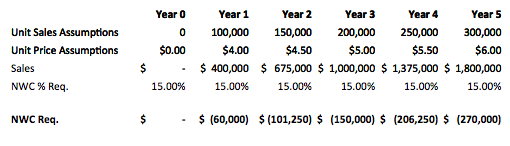

They will also require additional NWC totaling 15% of annual sales. Assume sales of:

- Year 1: 100,000 reams at $4.00 per ream

- Year 2: 150,000 reams at $4.50 per ream

- Year 3: 200,000 reams at $5.00 per ream

- Year 4: 250,000 reams at $5.50 per ream

- Year 5: 300,000 reams at $6.00 per ream

Incremental Operating Cash Flows

- Incremental CFs are the OCFs of the project

- Operating Cash Flow (OCF) = EBIT + depreciation – taxes

- Be sure to include all relevant cash flows

- Erosions or Synergies

- Opportunity Costs

- Expansion Project

- Create Pro-Forma Income Statement to determine OCF

- Sales

- less Expenses

- less Depreciation

- Operating Profit (EBIT)

- less Taxes

- Net Income (NI)

- add back Depreciation ß b/c it is a non-cash expense

- Operating Cash Flow (OCF)

- Create Pro-Forma Income Statement to determine OCF

- Replacement Project

- Create a Pro-Forma Income Statement to determine Operating CF

- Δ Sales

- less Δ Expenses

- less Δ Depreciation

- Δ Operating Profit (EBIT)

- less Δ Taxes

- Δ Net Income (NI)

- add back Δ Depreciation

- Δ Operating Cash Flow (OCF)

- Create a Pro-Forma Income Statement to determine Operating CF

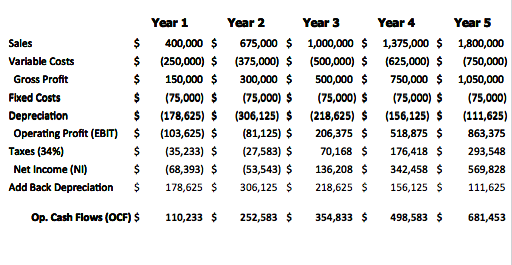

Example:

Financial analysts have estimated the following operating costs for the Philadelphia branch:

- Variable Costs of $2.50 per ream

- Fixed Overhead Costs of $75,000 to pay employee salaries and utilities.

- Assume Taxes of 34%

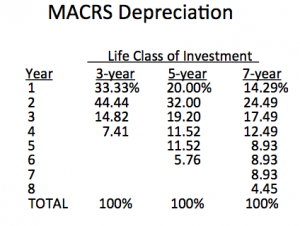

Depreciation

- Straight-line

- D = (initial cost – salvage value) / estimated life

- Very few assets are depreciated straight-line for tax purposes

- MACRS

- Need to know which asset class is appropriate for tax purposes

- Ignores salvage value and adds mid-year convention

Example:

Michael Scott, head of the Scranton branch, has decided that the Philadelphia Branch, being largely industrial equipment, should be depreciated according to the 7-year MACRS schedule.

Terminal Cash Flow

- Salvage Value of New Investment

- less taxes

- Salvage Value of Old Asset (if replacement)

- less taxes

- Other “terminal” inflows / outflows associated with both the new asset and the old asset

- Book Value & Market Value

- Are usually different

- The book value is the amount on the balance sheet, and equals the initial cost minus accumulated depreciation

- The market value of an asset is what you could sell it for

- Estimating Salvage Values

- What you think you could sell the equipment for when the project is over.

- Don’t forget taxes

- Tax liability = tax rate x (salvage value – book value)

- After-tax salvage value = Estimated salvage value – tax liability

Example:

Financial analysts have estimated that the Philadelphia branch can be sold at the conclusion of the five-year project for $500,000.

After tax CF from Salvage = $500,000 – $75,183 = $424,818

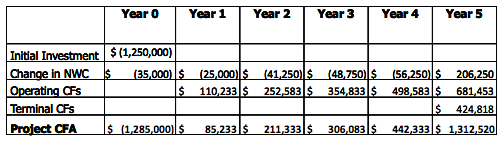

Completing the Capital Budgeting Analysis

Project Cash Flows = Initial Investment + Change in NWC + Incremental CFs + Terminal CFs

- Once you have the project cash flows, discount them at the appropriate cost of capital to find their net present value.

Example:

- Should Dunder Mifflin go through with the expansion to Philadelphia if the relevant discount rate is 10%?

- What is the NPV of the expansion project?

- What is the Payback of the expansion project?

- At what rate would they be indifferent to undertaking the project?

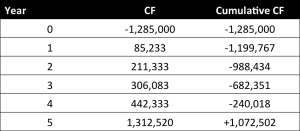

- NPV = -1,285,000

- + 85,233/(1.10)^1

- + 211,333/(1.10)^2

- + 306,083/(1.10)^3

- + 442,333/(1.10)^4

- + 1,312,520/(1.10)^5

- NPV = $314,196

- PB = 4 + (240,018/ 1,312,520)

- PB = 4.18 years

- IRR = 16.25%

Evaluating Net Present Value Estimates

- The NPV estimates are just that – estimates

- Develop framework to help identify areas where potential errors exist in estimates and to assess how much damage errors may cause

- Forecasting Risk

- How sensitive is our NPV to changes in the cash flow estimates?

- Sources of Value

- Why does this project create value?

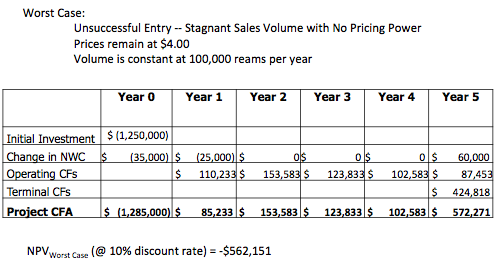

Scenario Analysis

- What happens to the NPV under different cash flows scenarios?

- At the very least, look at:

- Base case – this is what we have done

- Best case – revenues are high and costs are low

- Worst case – revenues are low and costs are high

- Best case and worst case are not necessarily probable; they can still be possible

Sensitivity Analysis

- This is a subset of scenario analysis where we are looking at the effect of specific variables on NPV

- What happens to NPV when we vary one variable at a time

- The greater the volatility in NPV in relation to a specific variable, the larger the forecasting risk associated with that variable and the more attention we want to pay to its estimation

Making a Decision

- Beware “Paralysis of Analysis”

- At some point, you have to make a decision

- If the majority of your scenarios have positive NPVs, then you can feel reasonably comfortable about accepting the project

- If you have a crucial variable that leads to a negative NPV with a small change in the estimates, then you may want to forgo the project

· · · · ·

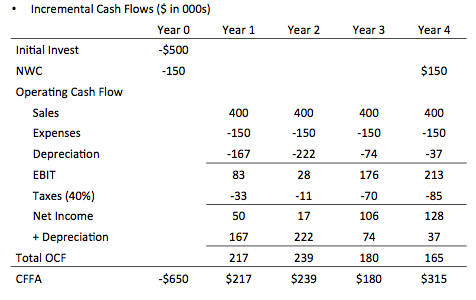

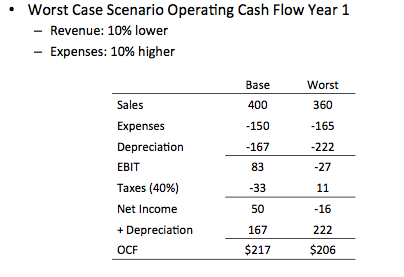

Test Your Knowledge (answers found below)- A $500,000 investment is depreciated using a three-year MACRS class life and has no salvage value by the end of year 4. It requires an initial investment of $100,000 in additional inventory and a $50,000 cash buffer, which are recovered at the end of the project. It will generate $400,000 in revenue and $150,000 in cash expenses annually for four years, and the tax rate is 40%.

- What is the incremental cash flow in each year?

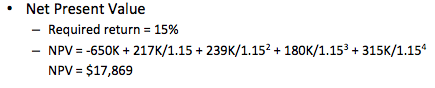

- What is the NPV of the project if required return is 15%?

- What is operating cash flow in year 1 given worst case scenario (revenue 10% lower and expenses 10% higher)?

Wrap-Up

- Focus on relevant cash flows when analyzing a project

- NPV estimates are only estimates and must be tested

· · · · ·

Solutions

For more classes:

Education Series

About the Author: Victoria Tran

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.