For many investors, the superiority of passive investing over active investing is axiomatic (Earth to passive investors; Lunch is never free!)

Study after study has demonstrated that only a small portion of actively managed funds beat their benchmarks over long time frames. A recent Wall Street Street Journal article, “The Dying Business of Picking Stocks,” noted that while 66% of mutual funds and ETFs are currently actively managed, this figure is down from 84% 10 years ago.

For many investors, the move into passive investing is simply another form of short-term performance chasing, but for others, the move is much more strategic and backed by persuasive logic. For example, back in 1991, William Sharpe published “The Arithmetic of Active Management,” which laid out the challenges faced by the active-management industry. Mr. Sharpe argued the market is made up of two kinds of investors: 1) passive investors, who hold the market-cap weight of every stock in the market, and never trade, and 2) active investors, who individually hold portfolios that differ from the market, and actively trade.

Mr. Sharpe’s “arithmetic” concluded the following:

- Passive investors earn market returns

- Active investors play a zero-sum game–for every winner, there is an offsetting loser.

The implications are profound for active investing because after deducting management fees, active investors must underperform passive investors, on average. The natural conclusion is for investors to simply punt on higher fee active management and invest all their capital in ultra-low-cost passive strategies.

Mr. Sharpe’s logic is compelling, but perhaps the assumptions underlying the conclusions are not grounded in reality.

Rethinking the Sharpe Critique

A recent essay by Druce Vertes at the CFA Institute, and more formal research by NYU Professor Lasse Pedersen (also has an AQR affiliation), suggests that Mr. Sharpe’s conclusions might be incorrect. Dr. Pedersen offers a very powerful critique in a new white paper entitled, “Sharpening the Arithmetic of Active Management.” Dr. Pedersen argues Mr. Sharpe’s arithmetic relies on the faulty assumptions that the market never changes and passive investors never need to trade.

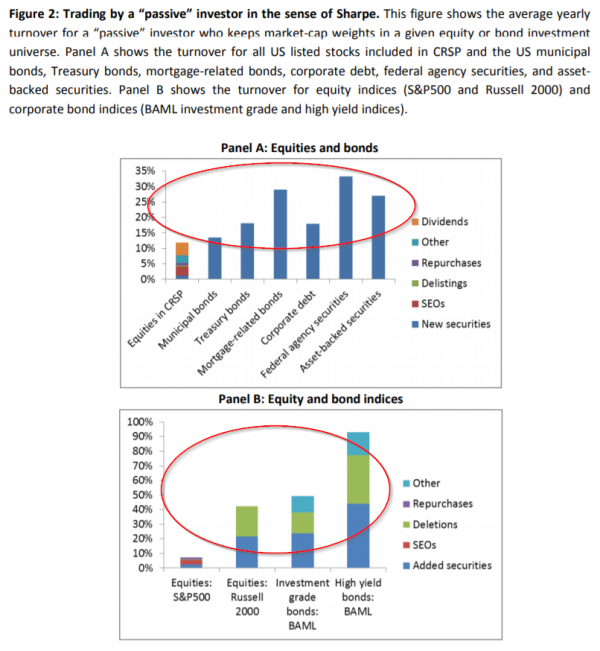

Objectively, these assumptions are false: The market is not static, as new firms are created through IPOs, new shares are issued or repurchased, and indexes are reconstituted all the time. Additionally, passive investors must sometimes rebalance their portfolios, for instance, to raise cash or reinvest dividends. In short, passive managers must trade with active investors. The chart below (from the paper), highlights this fact:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

As evidence for the need of passive investors to trade, Dr. Pedersen cites the case of a theoretical passive investor in 1927, who never trades. After 10 years, this investor owns only 60% of the market. And this ongoing market turnover is persistent: The average turnover for all equities from 1926 through 2015 was a whopping 7.6% per year. Last year, the Vanguard 500 Index Fund reported turnover of 10%. Clearly, the assumption that passive investors never need to buy and sell is false. And this mechanical need to trade opens passive investors up to exploitation by active investors.

But newly “passive” investors are only making matters worse by trading well beyond what they are required to do to maintain their passive exposure to an ever-changing market mix. The advent of cheap, liquid ETFs has increased trading activity. For example, in a recent essay titled “ETFs may actually make weak players weaker,” the author analyzed Morningstar data from the past five years, and found that ETF investors massively underperformed the very ETFs in which they were invested. These “passive” investors weren’t passive by any stretch of the imagination–they were active investors trading passive vehicles, providing opportunities for more sophisticated investors to exploit.

Focus on the Assumptions

Mr. Sharpe’s arithmetic relies on an assumption that passive investors never trade and simply buy and hold forever. This is an unrealistic assumption that thoughtful market commentators and researchers are now criticizing. The necessary trading required by passive investors to remain passive, and unnecessary trading by so-called passive investors trying to “time” the market with passive ETFs, change, in my opinion, Mr. Sharpe’s conclusions:

- Passive investors pay indirect fees to active investors for liquidity

- Active investing is no longer a zero-sum game.

The implications are more reasonable and reflect what we see in the marketplace: Passive investors no longer eat a completely free lunch, active investing still plays a role in the market, and a handful of puzzling societal problems associated with excessive passive investing no longer pose a problem for financial economists.

A triple win-win-win insight.

Note: A version of this was published by the WSJ here.

Sharpening the Arithmetic of Active Management

- Lasse Pedersen

- A version of the paper can be found here.

Abstract:

I challenge Sharpe’s (1991) famous equality that “before costs, the return on the average actively managed dollar will equal the return on the average passively managed dollar.” This equality is based on the implicit assumption that the market portfolio never changes, which does not hold in the real world because new shares are issued, others are repurchased, and indices are reconstituted so even “passive” investors must regularly trade. Therefore, active managers can be worth positive fees in aggregate, allowing them to play an important role in the economy: helping allocate resources efficiently. Passive investing also plays a useful economic role: creating low-cost access to markets.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.