Hyperbolic discounting and Present bias

Executive Summary:

“Intertemporal tradeoffs are ubiquitous in decision making, yet preferences for current versus future losses are rarely explored in empirical research. Whereas rational-economic theory posits that neither outcome sign (gains vs. losses) nor outcome magnitude (small vs. large) should affect delay discount rates…we show that whereas large gains are discounted less than small gains, large losses are discounted more than small losses…” —- Christine R. Harris, etc (2010).

Game 1: now or later?

- A: You are given a choice between receiving $80 now or $100 a year from now. What’s your choice?

- B: You are given a choice between receiving $80 in 10 years or $100 in 11 years. What’s your choice?

In case A, most people choose to receive $80 now rather than wait for another year. However, in case B, most people switch to the $100 option — a different choice — even though the option is essentially the same in the two cases. In the nearer period, where the choice is between today and a year from now, people prefer a smaller, immediate payoff over a larger, delayed payoff. However, when the same option is presented, but the two points in time considered are 10 (and 11) years out, people are more inclined to wait the extra year to get the larger payoff. There is something about the remoteness in time of the second case that makes people more inclined to wait for the higher payout. We have “present bias,” and can only discount appropriately when we are not thinking in terms of the present.

Game 2: feelings of dread

Another game is cited in a Christine R. Harris, etc. (2010) paper.

Below are two scenarios, and subjects are asked about their preferences with respect to timing of these occurrences. (Incidentally, the paper also contains 3 additional scenarios related to: 1) a painful bee sting, 2) an embarrassing experience, and 3) a close friend who tells you they want nothing more to do with you)

- Monetary gain (You win $100 door prize)

- Monetary loss (You lose $100 from your wallet)

Here are three different choices you are going to make with respect to each: would you prefer the event (monetary gain/loss) to take place….

- tonight or in 1 week?

- in 1 week or in 1 year?

- tonight or in 1 year?

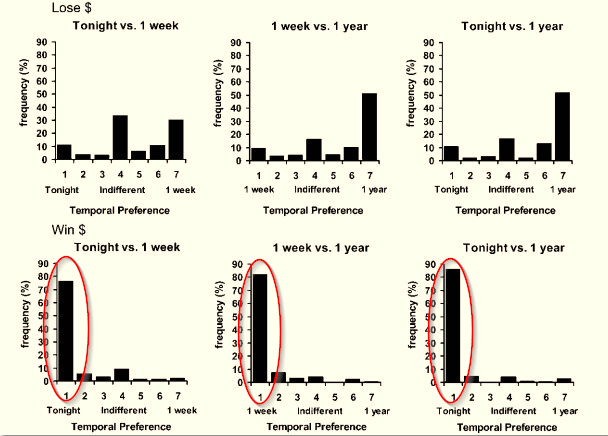

The results of 184 participants are shown below: In the monetary loss scenario, people tend to want to postpone the loss. In the monetary gain scenario, most people want the gains now.

* 7-point scale, where 1 meant ‘‘definitely prefer’’ the earlier option, 4 meant ‘‘indifferent,’’ and 7 meant ‘‘definitely prefer’’ the later option. Source: Christine R. Harris, etc. (2010). “Feelings of dread and intertemporal Choice”. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making.

Clearly people tend to want to get the reward today, but push the pain of loss far into the future. Does this remind you of anything? This effect is similar to an everyday phenomenon with which all of us are familiar: procrastination.

Say you have a project due tomorrow, and you have only one day to do the job. The prospect of experiencing a lot of pain makes you want to do some things you enjoy doing first, before you have to experience that pain. So you decide to take 20 minutes to surf the internet, but when you finally close your Facebook page, suddenly you realize an hour has passed. Next, you decide to take 10 minutes to have a cup of coffee, and a bite to eat, and then you watch some youtube videos while eating, and suddenly another hour has passed. Then your friend calls you and you talk for awhile on the phone. Then, surprise! It’s lunch time, and after a sandwich you feel a little sleepy so you take a nap. Then, after the nap, it’s already the late afternoon. You have consistently chosen rewards NOW, and pushed the painful project further and further into the future.

Now that’s procrastination! Obviously the problem comes when we are so present-biased with respect to pleasure that we wait too long, and do a bad job on the project since we allocate insufficient time to it. We have failed to properly discount pain at a future time, by applying an overly high discount rate to it. We might often do better to postpone the pleasant experiences, and instead suffer the pain immediately.

Applications in Finance:

Our tendency to improperly discount gives rise to the “disposition effect,” which is well known in finance. It describes how investors are reluctant to realize losses, and too quick to realize gains. There are several reasons why this can result in poor decision-making:

As discussed, w have a bias for the present. This affects us in both cases: 1) With winners, we put too high a discount rate on future firm prospects, placing too much emphasis on today’s pleasurable gains. 2) With losers, again we place too much emphasis on the pain we will feel today, preferring to postpone it. Our hyperbolic discounting makes us do the opposite, in both cases, of what we should do. There are few real-world factors that compound these mistakes:

- Taxes. When you sell a loser, you create a loss that reduces your taxable income. By contrast, when you sell a winner, you generate a taxable event. By holding onto losers and selling winners, we are creating a reverse tax arbitrage.

- The momentum effect. Stocks that have gone up in the recent past tend to continue to go up, while stocks that have gone down recently, tend to keep going down. Selling winners eliminates your ability to profit from momentum. Holding losers means you are systematically exposing yourself to stocks that have negative momentum.

Further Resources:

- David J. Hardisty, Kirstin C. Appelt and Elke U. Weber. (January 2012). “Good or bad, we want it now: Fixed-cost present bias for gains and losses explains magnitude asymmetries in intertemporal choice”. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making

- Christine R. Harris. (2010). “Feelings of dread and intertemporal Choice”. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making

About the Author: David Foulke

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.