I’ve been thinking about “extreme” returns recently. After all, who wouldn’t mind earning a few extra bucks in the stock market?

We all hear about quantitative strategies that are supposed to earn us 20%, 25%, or even 30%+ returns over long periods by simply “maintaining discipline to the strategy.”

Here are some examples we have discussed on our blog and have seen in the media:

- Goodwill Gone Bad, 23%

- Magic Formula, 31% (or less depending on how you do the calculations)

This all sounds great, but it is intellectually dishonest to not highlight the logical conclusion of such high returns. And I definitely do not want this blog to convey the idea that earning 20%+ CAGR for many years is by any means easy, or possible. Perhaps this is possible on a very small capital base, but over time, the returns on pretty much ANY strategy will slowly revert to a fair rate of return (risk and return are in balance).

Summary Findings:

Before I even begin, here are some findings (I use the CRSP return database which starts January 1, 1926 and runs through December 31, 2010):

- Earning 20%+ returns over very long horizons is for all intent and purposes virtually IMPOSSIBLE (assuming the market experience of the past ~90 years is representative of the future).

- 31.5%+ returns over the 1926 to 2010 period imply that an investor will end up owning over half of the ENTIRE stock market.

- 33%+ returns imply that an investor will end up owning the ENTIRE STOCK MARKET!

- A 40% return will have you owning the entire stock market in ~60 years–not a bad retirement plan!

- A “doable” 21.5% a year implies an investor will own .62241% of the market at the end of 2010. With a $16.4 trillion total market value as of December 31, 2010, this would imply a personal stock portfolio worth $102 billion!!!

- Warren Buffett–and perhaps a very select handful of others–have been able to achieve 20%+ returns over very long time periods. These individuals represent some of the richest people on the planet because of this very phenomenon.

- An investor might have an epic run of 20% returns for 5, 10, maybe even 15, or 20 years, but as an investor’s capital base grows exponentially, the capital base slowly becomes ALL capital, and all capital cannot outperform itself!

Motivation:

I am continually haunted by a note I received from one of my dissertation advisors at the University of Chicago–Gene Fama. He wrote the a response to an early draft of my paper on Valueinvestorsclub.com. In the document I sent, I stated proudly: “…this paper shows value investors outperform the market” (where outperforming the market is defined as earning average excess returns after controlling for a variety of market risks). Here was the response:

“Your conclusion must be false. Passive value managers hold value-weight portfolios of value stocks. Thus, if some active value managers win, it has to be at the expense of other active value managers. Active value management has to be a zero sum game (before costs).”

To my chagrin, Fama’s comments were spot on…

I did not show that “value investors outperform the market”–far from it. I showed that “the small group of investors in Valueinvestorsclub.com outperformed the market,” but that did not imply value investors as a group outperform the market.

Regardless of the argument surrounding semantics, I learned a great lesson in arithmetic: value-weight market returns have to be representative of the collective investor experience, because the value-weight market return represents the return to all investors in the stock market. And for every active “winner” who ‘outperforms’ the market, there necessarily must be a “loser” somewhere along the line (for every buyer there is a a seller and for every seller there is a buyer).

To this end, I decided to perform some analysis of extreme market returns over long periods.

My main inspiration for this exploratory study is the well known behavioral bias that humans (including me) have a hard time understanding the implications of compound growth.

Here is a quick video from Chris Martenson that captures the concept very well:

Click to get the video: The Power of Compounding.

Any discussion on compound growth and the profound implications it has on life would not be complete without referencing Al Bartlett http://www.albartlett.org/index.html.

Results and Analysis:

To perform this pilot study I grabbed a time series of the value-weighted return (including all distributions) for the entire CRSP universe from 1926 through 2010 (represents virtually all stocks on the NYSE/AMEX/NASDAQ). If you are unfamiliar with CRSP, you can think of it as the closest thing we have to the “Total US market.” The Wilshire 5000 is the best “practitioner” analogy.

Aside from depth, the great thing about CRSP is the long history of the database (goes all the way back to 1926, and the organization invests a painstaking amount of time in ensuring the database is free from survivor bias). For further information, see the documentation on CRSP indices here.

With a large amount of monthly return data extending back to 1926, I started my analysis (FYI, you can access this data and much more at Ken French’s website).

Here was my approach:

- Start a “winner” portfolio on January 1, 1926 and invest at a given rate through December 31, 2010. For example, a 20% annual compound annual growth rate (CAGR) would imply a (1.2)^(1/12)-1 monthly return. Let’s pretend the “winner” portfolio invests in some objective quantitative value strategy that earns outsized returns.

- The winner portfolio starts off owning 0.00001% of the entire market as of Jan 1926. This amounts to a very modest sum of $2,709, because the market cap of all securities at the time was around $27,090,070,400.

- Start a “loser” portfolio that represents the ownership of the rest of the market: ~$27,090,067,691. The loser portfolio returns the overall value-weighted market return minus the return it ‘lost’ to the “winner” portfolio.

- Quick example: The Jan 1926 overall VW CRSP market return (with distributions included) was .0724%. The “winner” portfolio–assuming a 30% CAGR–was 2.21%. The winner portfolio moves from 2,709 to 2,769, the entire market portfolio moves from 27,090,070,400 to 27,109,680,842, and the “loser” portfolio earns the ‘leftover’ after the “winner” portfolio takes their cut. Specifically, the “Loser” portfolio moves from 27,090,067,691 to 27,109,680,842 (27,109,680,842-2,769). In the end, the winner portfolio earns 2.21%, the loser portfolio earns .0723999%, and the entire market return earns .0724% (by construction, the value weighted returns of the “winner” and the “loser” portfolio must equal the actual value-weighted market return).

- Next, I extend this analysis to the entire time period to determine the following:

- When does the “winner” portfolio own over half the stock market?

- What % of the stock market does the “winner” portfolio own at the end of 2010?

- How do various assumptions about the “winner” portfolio CAGR affect the results?

Here is a table of results:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

What you should immediately notice is the implications of extreme CAGR and stock market ownership. Earning a high return eventually forces you to own a larger and larger percentage of the stock market.

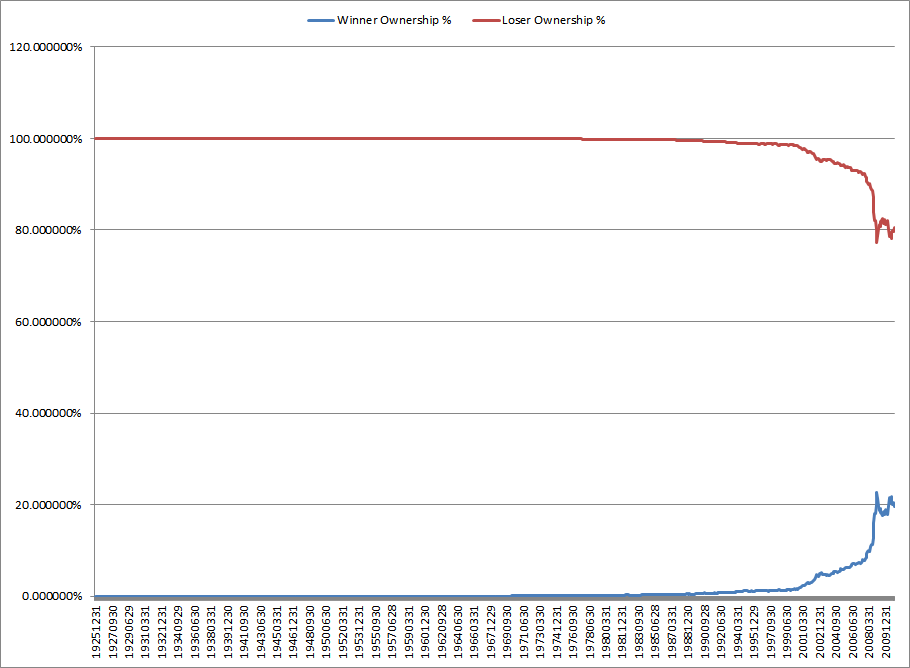

And here is a chart showing how ownership changes over time when the winner portfolio earns 30% CAGR.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

What you see is that the underlying 30% CAGR portfolio is slowly turning a mole hill into a massive mountain that eventually becomes the entire market.

Summary:

The point of this thought experiment seems to be quite clear:

Nobody–I repeat, NOBODY–can continuously outperform the market over long periods of time, because eventually this “genius” will own the market! And by definition, if you own the market, you can’t outperform the market.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.