Doubling Down

- Jonathan Rhinesmith

- A version of the paper can be found here.

- Want a summary of academic papers with alpha? Check out our Academic Research Recap Category.

Abstract:

I demonstrate that when investment fund managers “double down” on positions that have run against them, they outperform. Specifically, I find that a portfolio formed of the U.S. equity positions that hedge fund managers add to after recent stock-level underperformance generates significant annualized risk-adjusted outperformance of between 5% and 15%. This finding is not the result of a simple reversal effect, of a fund’s best ideas (large positions), or of the general informativeness of fund trades. My results are consistent with a career risks mechanism for this phenomenon. By adding to a losing position — the opposite of window dressing — managers are making their losses particularly salient. I demonstrate in a panel regression that investment managers avoid adding to losing positions. Furthermore, managers outperform by more when they double down after greater past losses in a position. These findings suggest a position-level limits to arbitrage effect. Even when an asset decreases in price for non-fundamental reasons, some of the investment managers with the most relevant knowledge of that asset may be particularly hesitant to add to their positions because they have already suffered losses in that asset.

Alpha Highlight:

When you hold a stock that plummets, you have three choices:

- sell and get rid of it — stop the losses

- hold and see what happens — disposition effect

- double down and buy more — believe there is a short-term mispricing and hope for a promising comeback

Under the pressure of career risks, mutual/hedge fund managers tend to “window-dress” before disclosing performances to clients, especially at the end of quarter/year. To “paint” a clean portfolio picture, and dress their window, managers sell those stocks with large losses, and buy stocks that have done well. Due to window-dressing pressures (which can also be due to tax efficiency or momentum signals), managers are sometimes hesitant to add more to a losing position.

In this paper, the author finds that despite these pressures, fund managers sometimes do make the tough decision and “double down.”

When fund managers “double down” on recent losing positions, those portfolios tend to outperform!

Key Findings:

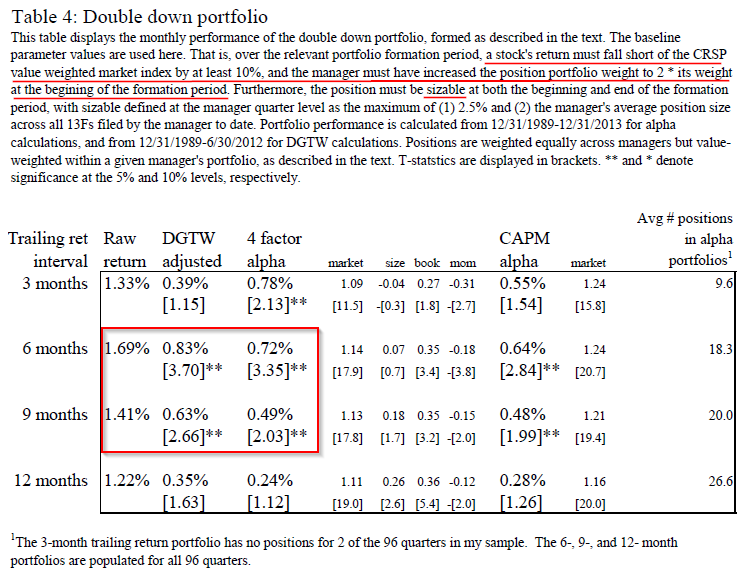

- With a sample from 1/1990 to 12/2013, the paper finds that a portfolio formed of the positions that fund managers add to after recent stock-level underperformance generates significant annualized risk-adjusted outperformance of between 5% to 15% (Table below shows the monthly performances). Double down portfolios perform best with around a 6 to 9 month holding period.

* Note the underlined sentences define the doubling down portfolios in this paper.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

How to explain the “doubling down” effect?

The paper then constructs a variety of control portfolios to demonstrate that the “doubling down” effect is not explained by a simple reversal effect, or by the general informativeness of fund trades. Rather, the author contributes this effect to “career risk” of fund managers. The paper measures managers’ portfolio returns over recent quarters, and compares them to returns earned by other managers. If a manager has outperformed recently versus peers, the manager is assumed to have relatively lower career risk. If a manager has underperformed recently versus peers, the manager is assumed to have relatively higher career risk. The paper finds some evidence that managers who have done well recently (lower career risk) are more likely to double down as compared with managers who have done worse recently (more career risk). These lower performing managers might be more inclined to window dress and less inclined to double down due to the career risks they face. Perversely, a manager’s recent underperformance may drive him to make more bad decisions. By contrast, a high performing manager, who is more secure in his job, may have more confidence to double down on a position that has moved against him.

To be specific:

- By adding to a loser, fund managers usually call more attention to their decisions. So the doubling down decisions represent a clear demonstration of the information content of a fund manger’s decisions.

One potential downfall from a double down strategy — overconfidence.

Time to double down on your losing stocks?

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.