Warren Buffett make it clear why frequent trading damages one’s wealth:

“Wall Street makes its money on activity. You make your money on inactivity.” (source)

But is activity always a bad thing?

Implicit in Buffett’s quote is an assumption that frictional costs outweigh any benefits of enhanced returns due to increased activity. Surely this is true for retail investors with high transaction costs, and it is probably true for vast swaths of active professionals, but does this assumption hold for all professional active investors? New research from professors at The Wharton School and the Booth School of Business suggest otherwise. Drs., Pastor, Stambaugh and Taylor actually find that active mutual funds perform better after trading more. They find this result is especially true for small funds with high expense ratios (sometimes you might actually get what you pay for in active management).

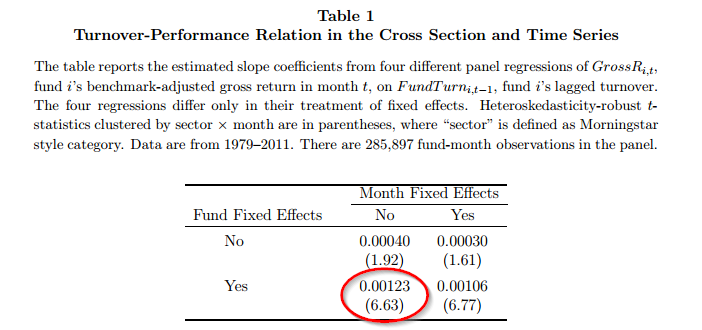

Digging in the weeds, the authors examine a sample of 3,126 active funds from 1979 through 2011. Next they estimate the relationship between a fund’s turnover and a fund’s subsequent performance. The core result is surprisingly robust and significant: a standard deviation increase in turnover is related to a 65bps increase in subsequent annual performance. The 65bp figure is derived by taking the regression slope estimate in Table 1 (bottom left item is .00123), and multiplying the slope estimate by the within-fund standard deviation of turnover in the prior period (.0438), and then multiplying (.00123*.0438) by 12 to get a simple-compounded annual figure of 65bps.

The results for smaller, higher-fee funds are even more pronounced. A one standard deviation increase in turnover tends to translate into 125bps a year in additional performance.

So far, so good. But all we have to go on is some fancy statistics that show a relationship between turnover in the current period and future performance. How might this work as a portfolio construct? To address this concept, the authors go long a portfolio that buys funds that have high recent turnover, relative to their own history, and shorts funds that have low recent turnover, relative to their own history.

Obviously, one could not implement this approach in practice, but the exercise is meant to identify if high recent turnover actually leads to measurable out-performance.

The results for this experiment are presented in table 10. The difference in returns between the high recent turnover and low recent turnover portfolios are 5.24bps a month. When the authors look at high-sentiment periods (when there are more active trading opportunities), the spread in returns is even higher at 8.74bps a month.

There are many other tests conducted by the authors, but the core takeaway is the same: there is evidence of skill among active mutual funds.

Important to note, these results do not suggest that active mutual funds are great investments. One would need to consider the management fees, taxes, and other considerations related to the strategies outlined in the paper (see our FACTS framework for manager selection). For example, in order to capture the expected benefits of the skill identified, an investor would need to know mutual fund turnover at month end (not possible with current disclosure rules) and have an ability to cost-effectively go in and out of funds at high-turnover periods. The negative results in Panel B of Table 10 highlight that while the authors identify skill, they don’t necessarily identify if investors will benefits from the skill. If one wants to assess whether an active fund will have sustainable out-performance, one would need to consider our sustainable active investing framework and the fees being charged by the manager.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.