In our final blog post, that finishes the trend-following series, we briefly review the results of the forward-tests of the profitability of various trend following rules in different financial markets: stocks, bonds, currencies, and commodities. The results of these tests allow us to better understand the properties of the trend following strategies, their advantages, and their disadvantages.

Prior to considering each specific financial market, let us elaborate on the factors that play role in the success of a trend following strategy.These factors are as follows:

These factors are as follows:

- The duration of a trend should be long enough to make the trend following strategy profitable. For the sake of illustration, consider the popular P-SMA(10) strategy which uses a 10-month simple moving average. We know (see Part 2 of this blog series) that SMA(10) identifies a turning point in the trend with the average delay of 4.5 months. Therefore, as a ballpark estimate, the duration of a trend should be no less than 10-12 months in order to make the P-SMA(10) strategy profitable. Since trends have various durations, longer trends should prevail over shorter trends.

- Whether the overall long-term market trend is upward, sideways, or downward. When the market trends strongly upward over the long run, bull markets are much longer than bear markets. Because short bear markets cannot be identified with a good enough accuracy, a trend following strategy is not profitable in these circumstances. A trend following strategy is usually profitable when the market goes sideways or downward over the long run. A possible indicator of the success of a trend following strategy can be the ratio of the average bull market length to the average bear market length. If this ratio is close to unity, then it indicates that the market has been going basically sideways and a trend following strategy may be highly profitable. The higher (smaller) the value of this ratio, the less (more) profitable a trend following strategy is.

- Bear markets should be not only long enough, but with a large enough price decrease. That is, generally the larger the drawdowns, the better the profitability of a trend following strategy. When the drawdowns are small and the price volatility is high, a trend following strategy is not profitable even if the ratio of the average bull market length to the average bear market length is close to unity.

When we talk about bull and bear markets, we talk about the so-called “primary markets” (a.k.a. “cyclical trends”); the length of these markets generally varies from one to five years. Besides the primary market trends, in each financial market one can easily observe the long-term trends known as “secular markets” or trends. A secular trend, which lasts from one to two decades, holds within its parameters many primary trends. For example, a secular bull market will have bear market periods within it, but it will not reverse the overlying trend of upward asset values. Similarly, a secular bear market will have bull market periods within it.

Why is it important to be aware of secular market trends? It is important because the dynamic of the bull-bear markets undergoes a regime shift when a secular market trend changes its direction. Specifically, a secular bull market is characterized by long bull markets and short bear markets. In contrast, a secular bear market is characterized by short bull markets and long bear markets. As a result, a trend following strategy outperforms its passive counterpart basically over secular bear markets. Over secular bull markets, on the other hand, a trend following strategy usually underperforms the corresponding buy-and-hold strategy.

Stock Markets

We tested the profitability of trend-following rules using monthly data on five stock market indices in the US. They are the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) index, the large cap stock index, the small cap stock index, the growth stock index, and the value stock index.

The DJIA index is a price-weighted stock index. Specifically, the DJIA is an index of the prices of 30 large US corporations selected to represent a cross-section of US industry. All other indices are value-weighted indices. The large cap stock index resembles the S&P 500 index. By definition, growth stocks (a.k.a. the “glamor” stocks) are stocks of companies that generate substantial cash flow and whose earnings are expected to grow at a faster rate than that of an average company. Value stocks are stocks that tend to trade at a lower price relative to its fundamentals and thus considered undervalued by investors. Common characteristics of such stocks include a high dividend yield, low price-to-book ratio, and low price-to-earnings ratio. Small cap stocks are stocks of companies with a relatively small market capitalization.

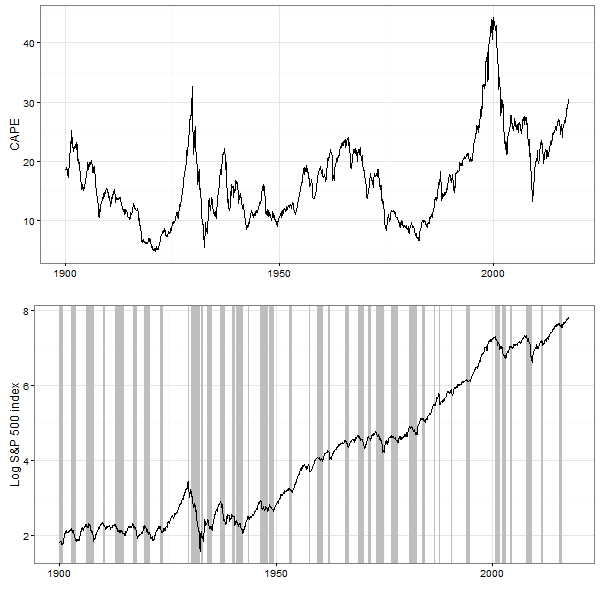

Before reporting the results of our forward tests, let us consider secular bull and bear markets in stocks. There is an extensive literature on the secular stock market trends, see, among others, Alexander (2000), Easterling (2005), Rogers (2005), Katsenelson (2007), and Hirsch (2012). The figure below, upper panel, plots the Shiller’s Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings ratio (CAPE) computed using the 10-year average earnings divided by the price of the S&P 500 index. The lower panel in this figure plots the natural logarithm (log for short) of the S&P 500 index. Shaded areas in this panel highlight the primary bear markets. A secular bull market is characterized by a long term increase in the CAPE and the stock prices. A secular bear market is characterized by a long-term decrease in the CAPE. During a secular bear market the stock prices go sideways. Researchers disagree on the exact dating of the secular bull-bear markets, but the approximate dating of these trends is as follows. From 1900 to date, there were three secular bull markets and three secular bear markets. Secular bull markets covered the periods from 1920 to 1929, from 1949 to 1965, and from 1982 to 2000. It is quite likely that the new secular bull market started in 2009.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

We remind the reader that the trend-following strategy usually underperforms the passive strategy during secular bull markets that, in the stock market, last from one to two decades. For example, the trend-following strategy underperformed the buy-and-hold strategy over the period from 1982 to 2000. No wonder that trend-following went out of favor by the end of 1990s. Trend-following trading became again popular in the aftermath of the two recent severe stock market crashes (the Dot-com bubble crash and the Global Financial Crisis). Many investors started implementing trend-following trading from about 2009. However, these investors were totally disappointed because the trend following strategy underperformed the buy-and-hold strategy on a year-to-year basis from 2009 to date. Nowadays trend following is probably again going out of favor. Even though there are lots of studies that document the profitability of trend-following rules over a long-term investment horizon, we guess that there is probably no one investor who actually benefited from trend following. This is because, as a rule, by the end of a secular bull market trend following is declared “dead.” Then, by the end of the subsequent secular bear market, trend following becomes again popular, investors start implementing trend-following rules, but this implementation usually coincides with the beginning of the next secular bull market where trend following does not work. This vicious circle is repeated throughout history.

There have been attempts (see, for example, Asness, 2014) to implement the trend-following strategy only when it is “most needed.” The idea that was entertained is to follow the buy-and-hold strategy when the CAPE is below its long-run mean, and implement the trend-following strategy when the CAPE is above its long-run mean. These attempts were largely unsuccessful because of the poor timing of secular bear markets. What is needed is to identify the direction of the long-term trend in the CAPE. One needs to follow the buy-and-hold strategy when the CAPE is trending upward over the long run. A trend-following strategy should be implemented when the CAPE is trending downward over the long run. However, because the secular cycles in the CAPE are of irregular length, their timing is exceedingly difficult.

Now we turn to the results of our forward tests. Our results suggest that the trend following rules statistically significantly outperformed the buy-and-hold strategy in trading the small cap stock index only. However, these trend following rules exploited the existed short-term momentum in the prices of small stocks. This short-term momentum ceased to exist in the early 2000s and was replaced by a short-term mean-reversion. Therefore we doubt that trend following rules will be profitable in trading the small stocks in the near future.

Robust positive, yet not statistically significant, outperformance was observed in trading the large cap stock index. Our results on the profitability of trend following rules in trading the large stocks agree with those in trading the S&P 500 index (see Part 7 of this blog series).

Our results revealed that trend-following rules are not profitable in trading all other stock market indices (the DJIA, value stocks, and growth stocks). Roughly, the out-of-sample performance of trend following rules in trading these indices was about the same as the performance of the corresponding buy-and-hold strategy. Yet, as compared with its passive counterpart, the trend-following strategy has both lower mean returns and risk. Why do trend-following rules not work in some stock markets? Unfortunately, we do not have clear-cut answers, we can only speculate on possible reasons.

Bond Markets

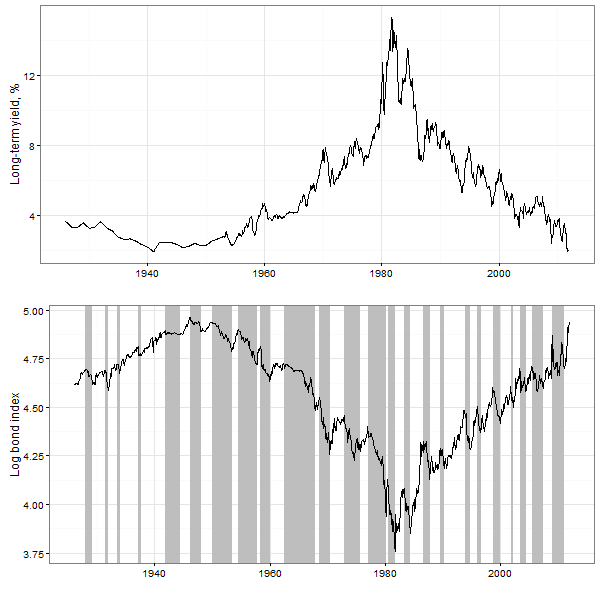

We tested the profitability of trend-following rules in bond markets. For this purpose, we used the data on two bond market indices: the long-term and intermediate-term US government bond indices. Before proceeding to the results, it is useful to analyze the dynamics of the bull-bear market cycles in these markets. The figure below, upper panel, plots the yield on the long-term US government bonds, whereas the lower panel plots the natural log of the long-term government bond index (not adjusted for cash flow from coupons). Shaded areas in the lower panel indicate the bear market phases. Note that our historical sample, that covers the period from 1926 to 2011, contains two secular bull markets and one secular bear market. The secular bull markets cover the periods from 1926 to the middle of 1940s and from 1982 to 2011. These secular bull markets are associated with two long-term periods of decreasing yield on the long-term government bonds. The secular bear market spans the period from the middle of 1940s to 1982 and is associated with a long-term period of increasing yield on the long-term government bonds.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

Our out-of-sample period starts at the beginning of the secular bear market and covers one secular bear and one secular bull market in bonds. The results of our forward tests revealed that trend following did not work in the bond markets. Specifically, the trend following rules outperformed the passive strategy during the secular bear market, but underperformed during the subsequent secular bull market. Overall, over the two secular markets, the estimated outperformance was slightly below zero. Interestingly, the secular bull market in bonds apparently contains enough primary bear markets; see the lower panel in the figure above. Yet, these bear markets had irregular and short lengths. As a result, trend-following rules, that were “trained” to recognize bear markets mainly during the preceding secular bear market, could not recognize bear markets during the secular bull market.

Currency markets

We forward-tested the profitability of trend following rules using a dataset consisting of six exchange rates. All data span the period from January 1971 to December 2015. The profitability of trend-following rules was evaluated from the perspective of a trader whose home country is the US.

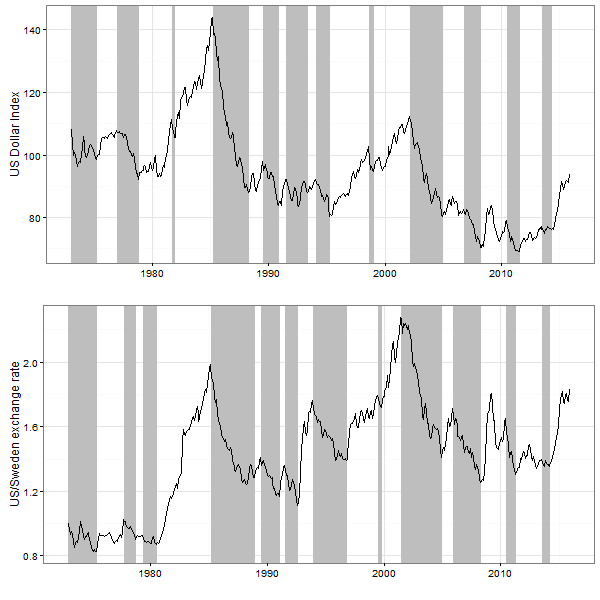

There have been conducted lots of studies where the researchers tested the profitability of technical trading strategies in currency markets. The great majority of these studies find profitability of technical trading strategies. However, several studies conducted in the early 2000s seem to suggest that technical trading profits have declined or disappeared since the middle of 1990s. The researchers jumped to the conclusion that the currency markets gradually became “efficient” which implies that it is not possible to “beat the market” consistently using the information from the past exchange rates. However, in our opinion this conclusion was premature. This is because during long-term periods where the US dollar strengthens (secular bulls market in the US dollar), trend-following strategies do not work. The fact is that since the early 1970s the US dollar tends to follow secular cycles lasting 5-10 years. The absence of profitability of technical trading rules over the period from the middle of 1990s to the early 2000s can be explained by the fact that over this historical period the US dollar was strengthening.

For the sake of illustration, the figure below, upper panel, plots a weighted average of the foreign exchange value of the US dollar against a subset of the broad index currencies. Shaded areas in this plot indicate the bear market phases. The graph in this panel advocates that there were two secular bull markets in the US dollar. The first one lasted between 1980 and 1985, whereas the second one lasted between 1995 and 2003. The first secular bull market was induced by increasing interest rates in the US and, as a consequence, high demand for the US dollar. The second secular bull market covers the period of the Dot-Com bubble when the Internet and similar technology companies experienced meteoric rises in their stock prices and attracted substantial international capital flows.

Many individual exchange rates follow the same pattern of strengthening and weakening as that of the weighted average of the foreign exchange value of the US dollar. The lower panel in the figure below plots the US/Sweden exchange rate. The dynamic of the US/Sweden exchange rate resembles the dynamic of the weighted average of the foreign exchange value of the US dollar. However, some individual exchange rates have different dynamics with their own particular bull-bear cycles.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

The results of our forward tests confirm that trend following is profitable in the majority of currency markets. We found that, among the tested individual exchange rates, trend following did not work in trading the US/South Africa exchange rate only. The reason for poor performance of trend following rules in trading this particular exchange rate is the fact that the South African currency (South African Rand, ZAR) has been strengthening virtually over the whole out-of-sample period except some short historical episodes.

Commodity Markets

Trend following rules are exceedingly popular in commodity markets and the majority of research studies find the profitability of technical trading strategies. Our forward tests also confirm that trend following rules are profitable in trading all commodities in our dataset.

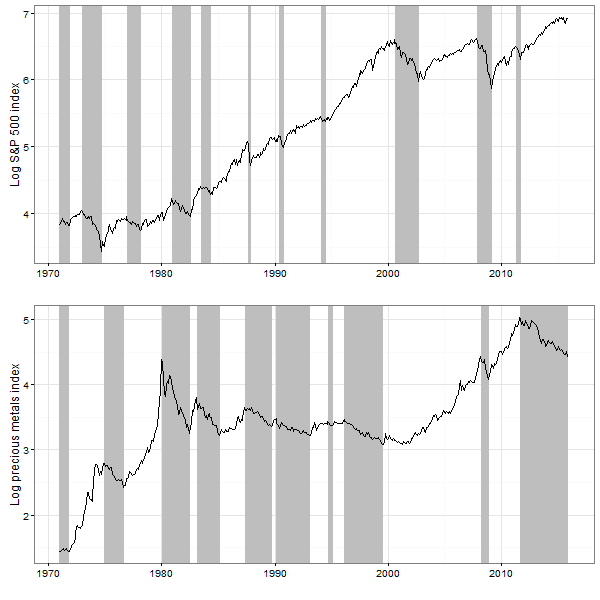

Interesting and relevant insight about the investment in commodities is this one: whereas stock prices are negatively correlated with inflation and interest rates, commodity prices, on the other hand, are positively correlated with inflation and interest rates (see Gorton and Rouwenhorst, 2006, and Kat and Oomen, 2007). Commodity prices are also negatively correlated with stock prices. Therefore, when stock prices go down, commodity prices usually go up (Rogers, 2007). To illustrate this feature of stock and commodity prices, the figure below, top panel, plots the bull-bear cycles in the S&P 500 index over the period from 1971 to 2015. The bottom panel in this figure plots the bull-bear cycles in the Precious metals index (gold, silver, and platinum) over the same period. The graphs in this figure suggest that when the stock prices go sideways (as in the 1970s and 2000s), the prices of precious metals increase substantially. That is, a secular bear market in commodities (at least in precious metals) largely coincides with a secular bull market in stocks. Similarly, a secular bull market in commodities largely coincides with a secular bear market in stocks. This knowledge suggests that a mixture of stocks and commodities achieves good portfolio diversification. In addition, the analysis of the dynamic of secular trends in commodities can potentially help to detect turning points in the secular stock market trend. For example, the bear market in precision metals began in 2011 and continues to date. This observation suggests that currently the stock market is in a secular uptrend.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

Summary and Additional Remarks

We tested the profitability of trend-following rules in different financial markets: stocks, bonds, currencies, and commodities. The results of our test allow us to draw the following conclusions:

- The trend-following rules are most profitable in commodity and currency markets.

- In stock markets the profitability of trend-following rules depends on the type of the stock price index. Statistically significant long-run outperformance was observed only in trading the small stock index; yet over the recent past the trading in small stocks became unprofitable. Trading in a well-diversified portfolio of large stocks seems to produce a robust long-run outperformance. However, this outperformance is not statistically significant at the conventional statistical levels.

- The trend-following rules did not work in bond markets over long-term periods that cover secular bull and bear markets.

- Outperformance delivered by the trend-following strategy is very uneven regardless of the type of financial market. Consequently, over a short-run there is absolutely no guarantee for outperformance even in commodity and currency markets.

- Regardless of the financial market, the trend-following strategy outperforms its passive counterpart basically over secular bear markets. Conversely, over secular bull markets the trend-following strategy underperforms the buy-and-hold strategy. In each financial market there are secular trends that last from 10 to 20 years. Consequently, the trend-following strategy might underperform its passive counterpart even over a long-run.

We also conducted forward tests to find out whether there is any advantage in trading using the daily data versus the monthly data. In principle, the daily data are freely available and it seems natural to expect that using the daily data may potentially improve the performance of the trend-following strategy. This is because the high-frequency data are supposed to provide earlier Buy and Sell trading signals. The results of our tests suggest that there is no advantage in trading daily rather than monthly. The most likely explanation of this result is that daily data are much noisier than monthly data; the daily signal-to-noise ratio is much smaller than the monthly one. This feature makes the detection of a stock price trend more complicated with daily data. Using monthly data instead of daily allows one to effectively increase the signal-to-noise ratio and make easier to distinguish the signal from the noise.

Overall, the investors must understand that trend following does not offer a simple, quick, and easy way to riches. Make no illusion, the profitability of these strategies is highly non-uniform over time and the investor may experience a prolonged period of consistent underperformance. Even though this underperformance is usually small, it may quickly disappoint the investor and make him abandon trend following. However, as compared with passive investment strategies, trend following strategies are less risky and able to limit the potential losses. Therefore over a long-run the outperformance generated by these strategies usually overbalances the underperformance.

References

Alexander, M. A. (2000). “Stock Cycles: Why Stocks Won’t Beat Money Market Over the Next Twenty Years”, iUniverse Star.

Asness, C. (2014). “Alternative Thinking: Challenges of Incorporating Tactical Views”, white paper, AQR Capital Management.

Easterling, E. (2005). “Unexpected Returns: Understanding Secular Stock Market Cycles”, Cypress House.

Gorton, G. and Rouwenhorst, K. (2006). “Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures”, Financial Analysts

Journal, 62 (2), 47–68.

Hirsch, J. A. (2012). “The Little Book of Stock Market Cycles”, John Wiley and Sons.

Kat, H. M. and Oomen, R. C. (2007). “What Every Investor Should Know about Commodities Part II:

Multivariate Return Analysis”, Journal of Investment Management 5, 40–64.

Katsenelson, V. N. (2007). “Active Value Investing: Making Money in Range-Bound Markets”, Wiley Finance.

Rogers, J. (2005). “Hot Commodities: How Anyone Can Invest Profitably in the World’s Best Market “, Random House Publishing Group.

About the Author: Valeriy Zakamulin

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.