Editor’s Note: this post has nothing to do with finance. Skipping this post costs you nothing. We encourage you to not read this post if you are only here to “geek out.” This post is angled towards those interested in the Leadville 100 ultramarathon, mountain adventures, and/or those in need of a reminder that when things are looking bleak, always remember — this too shall pass.

August 22, 2020 is the day that the Leadville 100 would have occured in a non-COVID world. A team from Alpha Architect participated in the event in 2019.

This monster post contains 3 sections: an overview of Leadville, information about preparation for the race, and a detailed play-by-play narrative of our experience at Leadville in 2019.

The mission of this story is to help others potentially improve their chance of success if they choose to explore one of the more eccentric challenges the world has to offer.(1)

Part 1: What is the Leadville 100 Trail Run and why would anyone actually run it?

Welcome to Leadville, CO. The highest incorporated town in the United States, at 10,152 feet. I grew up near Eagle, Co, which is not far from Leadville. And even as a kid, Leadville was always known as the place where “weird/crazy people live.” Beautiful locations with extremely rugged and harsh living conditions located deep in the Rocky Mountains tend to attract a unique crew of rednecks, yuppies, adventurers, misfits, and everything in between.

You can google “Leadville 100 trail run” (or hit the wiki or REI has a great story on the history of the Leadville 100) if you want to get the full back story on one of the most famous adventure races in the world, but I’ll summarize:

- In the early ’80s, the mining-centric town of Leadville, CO essentially goes bust. Unemployment is viral.

- Ken Chlouber and co. came up with the idea of an insanely challenging 100 mile foot race as a way to bring tourism dollars to the area (and probably as a way to take his mind off their current economic woes too!).

- The event would be called “The Race Across the Sky” and would take place above 10,000 feet in elevation and force you to plow through multiple mountain passes and challenging terrain.

- The first race started in 1983 and the event has been going strong ever since.

Nice work, Ken!

Why Did We Run the Leadville 100?

What actually pushed me (and Amy, and Pat, and Ryan and around 828 others) over the edge to run a 100-mile mountain race in August 2019? I’m still not sure. And to add to the confusion, I want to make one thing very clear: I am NOT an endurance athlete. I played football in high school and did track and field in high school/college. My main event was the pole vault, where the running requirement is less than 120 feet and I was totally happy with that distance. Eventually, I was introduced to endurance training when I was in the Marines, but running long distances isn’t my natural “thang.” I actually hate running to be completely frank.

So why did this happen?

To make a long story short, an old friend/client called me out of the blue in December 2018 and challenged me on the spot and claimed that if I didn’t try it I was a failure. Of course, I have the mindset of a kindergartener, so when someone calls me a sissy on the playground, I have to respond. Not to mention I was caught flat-footed and really didn’t have any great excuses as to why I wasn’t able to accept the challenge. Had I been more prepared I would have certainly found a way to say “No.” But I wasn’t prepared and the cause we were running for was right up my alley (CAF’s Operation Rebound program, which is focused on service members/first responders) and I figured the event would help me prep for March for the Fallen in September. “Win-win,” I thought.

Of course, misery loves company. And despite my clear understanding that this was a terrible idea, I immediately went to selling this idea to the only people silly enough to accept a terrible pitch: my sister-in-law Amy Gray, and my business partners Ryan Kirlin, and Pat Cleary.(2)

Looking back, I’m still not really sure why any of us actually said, “yes.” Everyone probably has a different reason. For me, maybe it was a midlife crisis at 39 years old. Maybe it was a sense that I was getting “soft” after poisoning my mind with too many Goggins, Jocko, and PatMac videos. Who knows. My speculation: I am a Colorado native and grew up fairly close to Leadville as a kid. The town always fascinated me. Everything about the area is hardcore — the weather, the wildlife, the mountains, and the people. I also grew up hearing about the race, but never really considered actually participating. In the end, I think I simply had a “fu#$ it, let’s do it” moment. A lapse in judgment: nothing more, nothing less.

Part 2: How Do You Prepare for the Leadville 100?

There are a thousand theories on how to prepare for the event. Everyone is different. You obviously need to put your time in on the trails — no human can finish the Leadville Trail Run 100 (LT100) off the couch.(3) But you also don’t need to dedicate your life to running if you want to try the Leadville 100. In my situation, I hate running and I have limited time because I have a young family with 3 kids and serve as the team leader for a fast-growing and entrepreneurial business, Alpha Architect. My training focus was on getting the job done with the least amount of effort possible, not to perform at the highest level possible. Disclaimer: if you have different race goals, my advice is probably worthless.(4)

Looking back, I can summarize the 3 aspects of preparation into 3 buckets from least important to most important: physical capability, nutrition/sleep, and mentality.

Physical capability

Note: There are probably thousands of books you can buy that outline different theories and training programs to finish the LT100. I actually read quite a few of them but didn’t really follow any of them. What I describe below is my minimalist approach to training for this event. And it worked, for me. That doesn’t mean it will work for you, but at least you have a data point (n=1) that simple can be effective.

A 100-mile race over mountains means you need to harden your ligaments and bone structure to withstand constant beatdowns. But you need to train smarter, not harder. Too much training will lead to injury, too little training will lead to failure. On the physical component, I have limited time so I would do my standard functional fitness type workouts during the week — 3 to 4 times, 15-25 minute intense sessions, ranging from powerlifting movements to bodyweight calisthenics. Think DIY CrossFit. These efficient workouts served as my cross-training to ensure that my muscles and connector-tissues were robust. Or at least that is what I told myself. The reality is that I think I got lucky I did this sort of training because the real reason I maintained this training regime is that I didn’t want to become a distance runner freak who couldn’t deadlift a paperclip. But I digress…

On the running side of the house, I’d contain this to weekends. I would fire up some music and finance/geek podcasts, head out on the trails fairly early, and perform what I call back-to-back “grinders”. I started off with 5 miles Saturday and 5 miles Sunday and I built up the mileage each week, based on how my body felt (some weeks I would drop mileage or put on a ruck and walk). Eventually, you can build yourself up where you end up doing back-to-back marathons on the weekends. I think the most I ever did was a 30 mile Saturday and a 25 mile Sunday. We also participated in the “Dirty German” 50-mile race around Philly (I think I may have finished dead last). It was a great opportunity to test my gear and my fitness in a real-world situation, but I actually don’t recommend too many crazy long runs (nor do the pros!). These long runs are great for “callousing the mind” (see below) but they also put you in a high-risk injury zone. Less can actually be more when it comes to ultra-marathoning.

My biggest advice on training is to listen to your body via an objective lens. Building an objective lens requires a dedicated “mentality training effort” (see below), to ensure you are fairly assessing what your mind is telling you, but the key thing to remember is the classic saying, “this is a marathon, not a sprint.” In the case of Leadville, that cliche deserves a solid, “No sh#$.” LOL.

Nutrition/Sleep

I am not a doctor. But there are plenty of doctors and PhDs who study nutrition/sleep as it relates to human performance (I like the Science of Ultra podcast). Learn from all of them and listen to people with polar opposite views. I learned a lot about this subject while training for the LT100. A fascinating topic. The journey made me much more empathetic for people who are entering the finance space and trying to understand fact from fiction. For example, in my case, understanding finance research and the substantive debate on everything under the sun seems normal and intuitive. I can maneuver the research with ease because that is all I have been thinking about for 10 hours a day for 20 years! But when I plowed into the nutrition world to try and find the right “answer,” I probably felt like people who enter finance and are trying to figure out which “factor” works the best. There is so much noise, no clear “experts” you can trust, and you end up wanting to pull your hair out. Ugg. Frustrating!

Unfortunately, I still have no clue on how to answer the question: “What is the best way to fuel your body?”

That said, with sleep, Matt Walker has convinced me that 1) more is better and 2) nobody gets enough. What I do think is that nutrition/sleep are critical elements of ultramarathoning success and arguably life success. I’m not going to go into great detail here since a discussion of nutrition can quickly turn into a political-like argument. But here are the key points in my mind:

- Sleep 8 hours a day (or more). Find-a-way. Prioritize it.

- Eat food. Not processed sh#$. Vegetarian? Great. Keto meat eater? Great. Cheetohs? Not great (unless its a snack on the run!)(5)

In my particular case, I upped my sleep, especially after grinder weekend workouts, and went on what I call a ‘plant-strong’ diet, which basically means you get 95% of your calories from plant-based sources. But I also explored the benefits of ketosis as it relates to ultra-endurance sports. I wasn’t going to starve myself and eat steak every meal like Mike Philbrick, so in my case, I used a compound called deltaG, which is an awful tasting, but very effective, cocktail that puts your body into chemical ketosis. See here for more info. (Zach Bitter, the 100-mile world record holder is a big keto guy and his story/logic is fairly compelling.)

Finally, I stopped drinking coffee and only saved caffeine for when I was going on 3hr+ training runs. Apparently, caffeine is an endurance performance booster (assuming your heart doesn’t explode), but the benefits are only realized if you aren’t adapted to caffeine in the first place. Wait a sec, “Wes, are you saying that I need to break my caffeine addiction?” My answer is “yes,” but recruit some help. For me, I convinced Chris Mendez (a lawyer/Marine friend) to serve as my motivation to quit coffee. Chris provided multiple psychologist sessions and performance motivation talks (ha!). In the end, I was successful. But I can attest that quitting coffee is possible, but not pleasant. Moreover, my wife sacrificed a lot so I could train for this stupid race, but her biggest sacrifice was quitting caffeine with me!

So what’s the bottom line on using performance enhancers to finish the race? I’m 100% down to do whatever it takes. Feel free to call me the Lance Armstrong of doing whatever I need to do (within the legal rules) to finish the event. And if you want to finish this event, you need to find ways to beg borrow and steal to maximize your shot at success, which includes giving up caffeine and saving its benefits for the race (and do some training with it along the way so you don’t have a heart attack).

Oh, I also came around to using beet juice, which is a favorite of endurance cyclists. Beet juice provides nitrates, which allows your body to process oxygen more efficiently (that’s what the scientists say, at least). I ended up using beat-ums, which is a good-tasting and easy to consume beet juice supplement. Highly recommended, but make sure you train with them to assess if your body can handle them during long runs.

Mentality

There are so many cliches that amount to “mind over matter.” These cliches have always rung hollow to me. Seemed like lots of talk, but very little action; my attitude was that the physics are either on your side, or they aren’t, because mentality isn’t going to deadlift 500lbs.

The LT100, which is the first challenge I’ve ever explored where I had heavy doubts I could actually accomplish the physical goal, convinced me beyond a shadow of a doubt that you can literally do anything you want, IF you put your mind to it. I have also been convinced that nobody is born with a God-given right to mental toughness– sure there is a bell curve, but “mentality” is a trained skill that can be improved over time via deliberate exercise and repetition.

Physics always matter, but “mental training” is by far the most important aspect of training for the Leadville 100. Goggins calls this “callousing the mind” and I am a big believer in this philosophy since I stumbled upon this concept while in the Marines. Folks who do yoga, meditation, or hang out in Tibet, etc. come to similar conclusions via different routes. I most easily relate to Goggins’ approach/lens because of our shared military experience/culture, but there are many methods available to manage your mentality (i.e., “control system 1” for you Kahneman geeks).

What is the “callousing your mind” theory?

In short, you can “train your brain” at the chemistry/structure level. This training builds your capacity to acknowledge “survival instincts,” appreciate what they are telling you, but also ignore what they have to say. For example, your mind may signal that you are fatigued or stressed. But are you really fatigued or stressed to such a level that you physically can’t move forward? Unlikely. Your brain is simply trying to help you survive and doesn’t want to waste energy on things that suggest you are entering the danger zone. And this is a good thing, normally. But the reality of any situation is that you can do whatever the fu#$ you want if you find ways to prevent your survival instincts from telling you that it is time to quit. (e.g., holding on to value stocks). The fascinating aspect of this theory is that it suggests that you can build up this “toughness” muscle via deliberate training. Of course, I am not an expert on this topic but my own personal experiments can confirm that the theory seems to work. Nobody is born hard. You need to build hardness. On the flipside, if you don’t train to be hard, you will become soft (something I am witnessing at the moment because being soft is very pleasant. Ha!).

How do you go about “callousing your mind” and creating a cyborg-like level of self-awareness?

Everyone is different and they will need to find a method that works for them. For me, it was simple:

- Step 1: find examples of insane freaks so your brain knows that what you are doing is possible. My best example is Courtney Dewaulter, who could do the LT100 in her sleep and could probably run the thing 3x in a row.

- Step 2: engage in extremely miserable physical activity and explore how your mind communicates with your body. Learn to control your organic emotions.(6)

Pre-Race Preparation

Okay, so you’ve been training for 6-12 months and now you are getting close to the event. Time for pre-race preparation!

The Leadville 100 Run website has tons of great links and information (for example, here is their gear list link, which is extremely helpful).

There are also countless other resources out there if you simply “google” the event. I recommend you check them all out, but here are some resources that we found particularly useful:

Route planning/calculators

- The official Leadville 100 pace chart calculator.

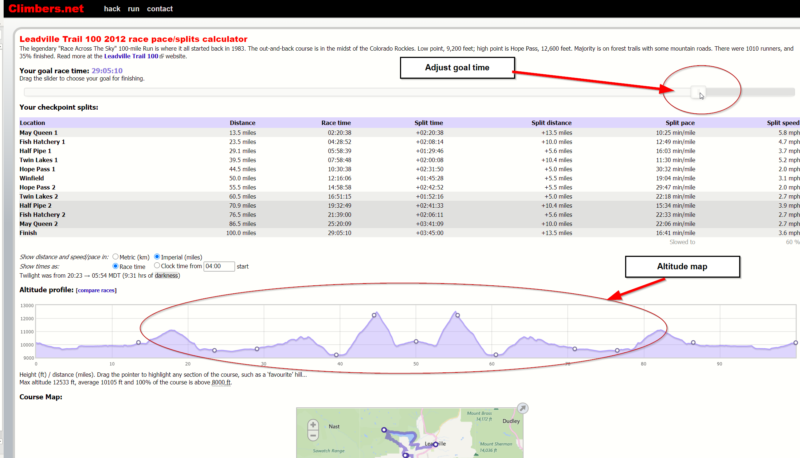

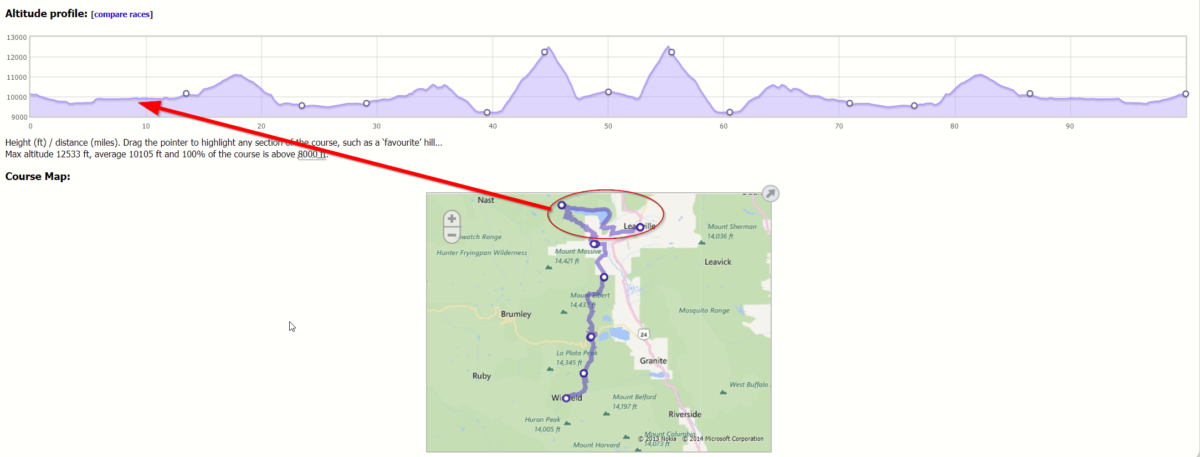

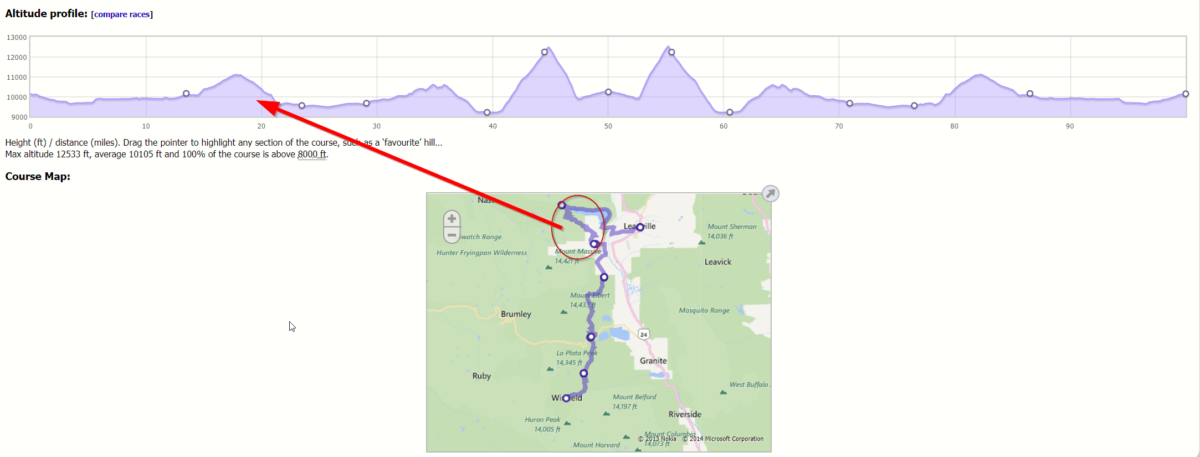

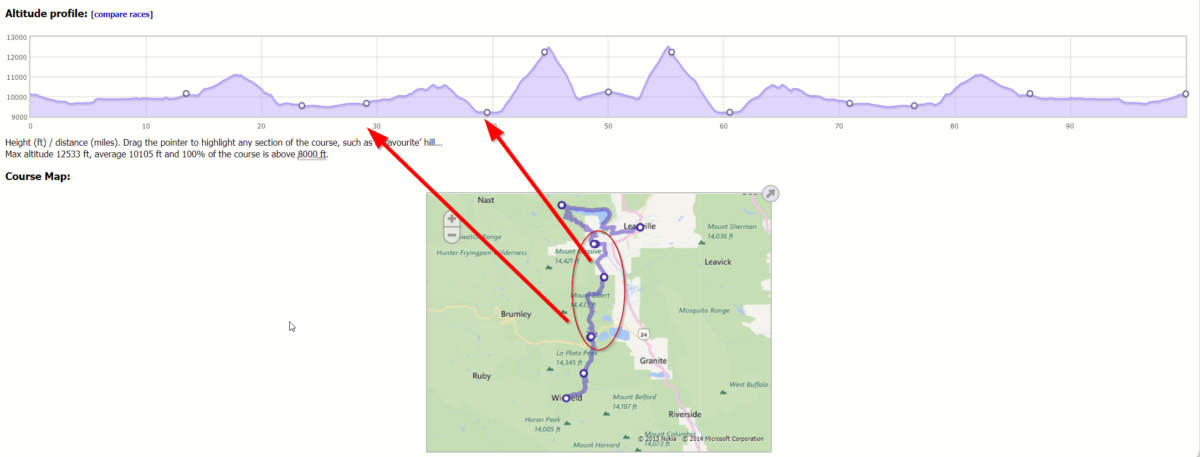

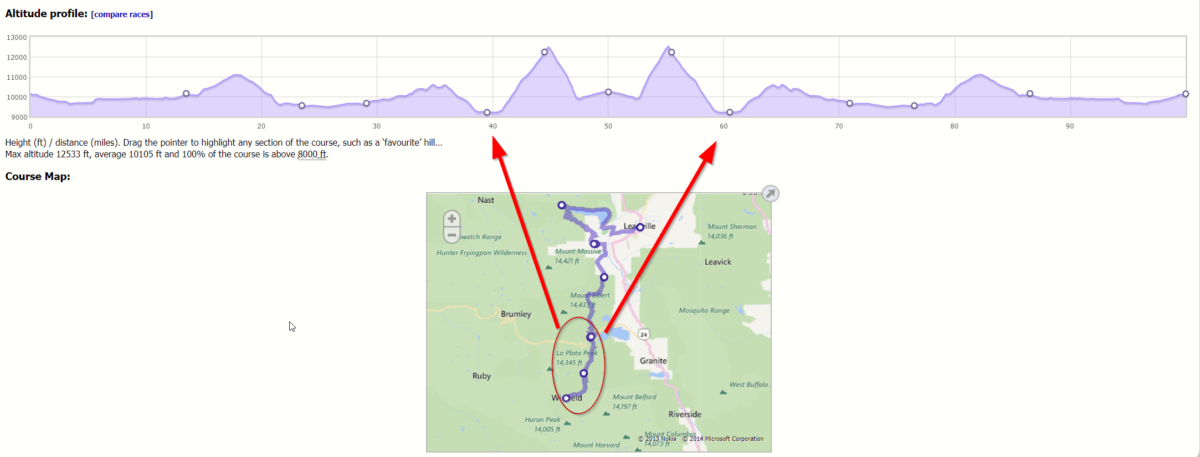

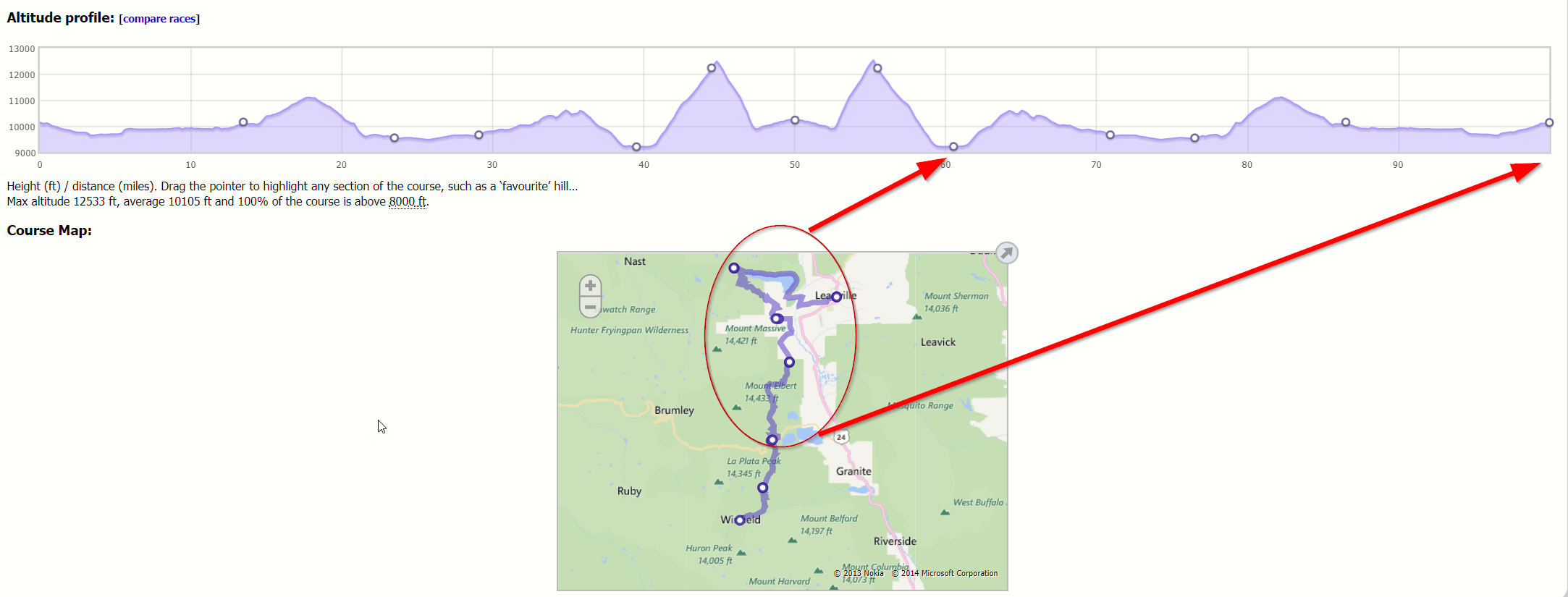

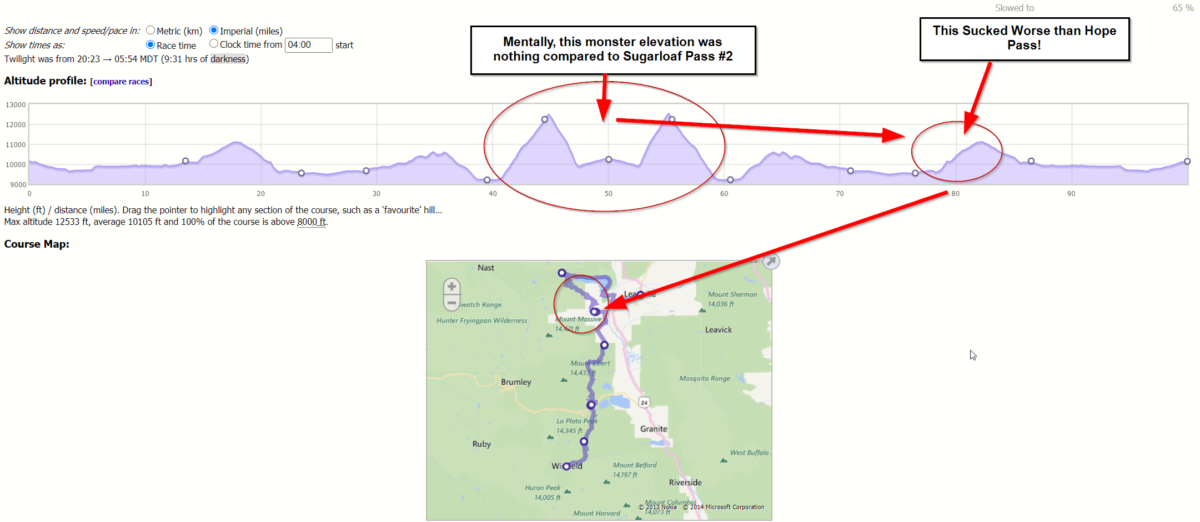

- Climbers.net calculator. This site is absolutely incredible and I use screenshots from their website throughout the guide below. A must-have website for any potential LT100 participant. Below is a screenshot from the site with some notes on the key features. The data is based on the 2012 course/numbers, so it may not be perfect, but it was very effective/useful for me and the rest of the team.

Journals and Resources

Everyone has a different take on the Leadville 100 experience and I encourage you to check them all out. I was constantly watching LT100 youtube videos and trying to learn more. But the most useful pieces for me were journals on live experiences from those who have tackled the course (I am doing my small part via this piece in hopes that it might help someone — even it if only helps a little — accomplish their goal of completing the LT100).

Some of my favorite resources are the following:

- Matt Carvalho — a 100-mile race finisher, a fintwitter, and RIA. Matt is a wealth of knowledge and he provided us some critical guidance on how to finish 100 miles.

- The Why: Running 100 Miles by Billy Yang. A great into to the Leadville 100.

- The Dana Roueche account.

- PDF version

- http://www.dclundell.net/running/info/train100.html

- A systematic approach to increasing the odds of finishing the L100. I’m a huge fan because Dana is obviously a quant!

- 2018 Official Leadville guide

- The official guide is filled with an insane amount of knowledge and details that you will need to know

- 2019 Official Leadville guide (similar to 2018, but I like reading different copies)

Pre-race prep involves identifying your pace between the checkpoints and the gear/nutrition requirements at each station. You also need to have branch plans/supplies for those inevitable episodes when the world goes to sh#$. The race itself is excellent and fully supported. So in theory, you could wing it with a hydration source and make it happen. Again, whatever works for you, this is your personal journey, not mine.

Here are a few photos of us doing pre-race gear prep. Unfortunately, I can’t grab a water bottle and go for it (well, maybe Goggins can, but not normal people). The biggest challenge is identifying your nutrition and hydration requirements and then figuring out when/where you will access them. You also need to have plans for crazy changes in the weather (ranging from really hot to snowing) and the associated gear required to literally (and figuratively) “weather the storm.” I recommend doing a few training runs to iron out any gear issues – you don’t want the first time you run with a headlamp to be out on the course!

Everyone has a basic load-out, but here are some of the items that were fairly unique/customized to my situation:

- cold weather gear prepared for entering Hope Pass and for the last 50 miles back (which are in darkness). Obviously, lighter and more efficient is better. I stuck to merino wool solutions and high-speed low-drag technical gear. With some careful shopping, I was able to score some deals on some nice gear. But even if you have to pay full price, it will be worth every penny. You don’t want to be a value investor when your life is at stake.

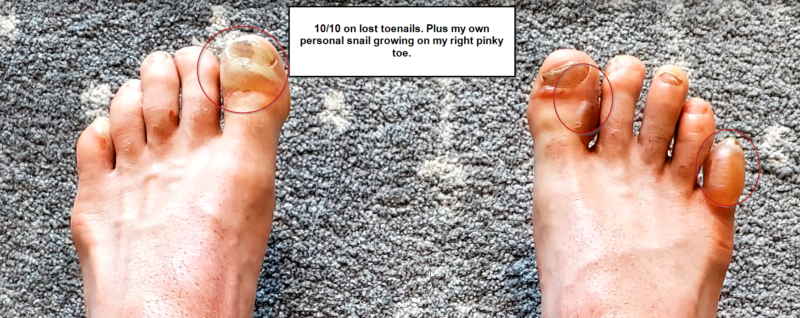

- 2 pairs of Hoka Speedgoat shoes. These are incredible shoes, but looking back I wish I stuck with a shoe that could accommodate a wider foot like a New Balance. Lesson learned after losing all my toenails.

- Ultimate direction trekking pack. I recommend a Camelbak hydration source stuffed in the back and use the front pockets for chow/gear. Bottles didn’t work for me.

- Trekking poles. I used these for 87/100 of the miles. I truly believe they save your infrastructure if you train with them. I would get poles that can be adapted on the fly. For example, going uphill I would shorten the poles so it was more efficient to grip into the mountain and pull myself up; going downhill I would extend them so I could “lean” on them and save energy. I would not have finished without poles. Montem carbon poles are affordable and bada$$.

- Supplemental nutrition: I needed a deltaG shot every 4 or 5 hours so I could drag my body into ketosis and minimize glucose burn. I also wanted a beet-um every 2 hours. I am also a fan of GU Roctane for long-haul training runs/events. A nice mix of water, calories and caffeine. During the event, I lived on this stuff!

- Leukotape: A Dave Babulak find that happened via MFTF training. The stuff is incredible and will solve a lot of problems on the course related to blisters, gear breaking, etc.

- Redundant light source: Keep a headlamp on you at all times. And extra batteries. Pay for quality/robustness. You don’t want a light failure along the way. (happened to me)

In the end, you can go nuts on gear, but you need the amount of gear that gives you the confidence to be successful. You also need to train on your gear, or as they say in the Marines, “Train like you Fight.” Inevitably, gear will break and you will be missing something along the way, but that is why mentality training trumps everything. Adapting and overcoming is always your mantra, but if you have a tight gear package/plan you can at least push reliance on your mind out to mile 60 and not mile 20.

What Happened at the 2019 Leadville 100?

A year ago this weekend (August 17, 2019), we managed to cross the finish line tragically stumble in immense pain across the finish line at the famous Leadville 100 Train run.(7) And I say “we” because I could have never survived the event alone. Seriously. I had the best Leadville pacer the world has ever known, Josh Russell, dragging my sorry excuse for a human across the line. Not to mention an entire crew of close friends and family manning an oar the entire time: my wife Katie & my kids, Rod/Nicole, Kirlin, Doug, Brandon, Granne/CJ, Cliff & Co., Cleary and Co., Debbie F., Tim M., the Delaney posse, and more.

Oh yeah, we were also running for the Challenged Athletes Foundation (CAF), a great charity that supports inspiring athletes with physical challenges. One of our brothers in arms at the event was the legendary David Goggins, who was also running for the CAF crew (albeit, way faster!). In the end, we raised over $9,000 for CAF and we are confident it is being used to make a positive impact for this awesome cause.

Did You Finish?

Yes. I finished. I was fortunate to finish under the 30-hour time limit in 2019 (29 hrs and 44 minutes!) in a year when the stars weren’t aligning for a lot of Leadville participants and the 30-hour finisher rate came in around 40% (typically it floats closer to 50%). This was accomplished with a mix of around 40 miles of running and 60 miles of power trekking up and down mountains. My original goal was to try and break 25 hours to earn the “big buckle,” but around 50 miles into the race I quickly fell in love with the idea of 1) surviving and 2) if I was lucky, earning the standard buckle by breaking 30 hours.

Official results from 2019 are available here.

But the real question is not “did you finish” the Leadville 100, but “Did you toe the line and learn something new about yourself?” If someone can answer “yes” to that question, that is the right answer and all that matters. Finishing is awesome, and I’m glad I did earn a buckle, but I was also lucky! There are so many variables that are outside the control of LT100 participants — weather, gear, nutrition, tweaked ankle, getting lost, and so forth — that even the most battle-hardened bada$$ mofo on the planet has a good shot at failure. Professional ultra-marathoners DNF (did not finish) all the time. And getting a DNF has no shame, especially on a rookie attempt, where the odds of success are probably less than 25% for first-timers.

The bottom line is that life is not about the scoreboard, it is about the process. Can you look yourself in the mirror at the end of the day and know that you did the best you possibly could with the God-given tools and the circumstances you were offered? If so, great; if not, improve your process.

Part 3: My Leadville 100 Journal (And My Pacer’s Journal via Josh Russell)

What follows is my play-by-play of the experience, interspersed with commentary from Josh Russell, a fellow PhD quant geek, who was generous enough to serve as my pacer on the back 50 miles of the LT100 run. Please reach out for additional questions/thoughts. We are always available to share tips/tricks to anyone who wants to try the LT100 run. Also, I will personally never run a 100-mile race again, but I will crew, pace, support your cause, and lend my 2 cents to anyone in the community who seeks the experience.

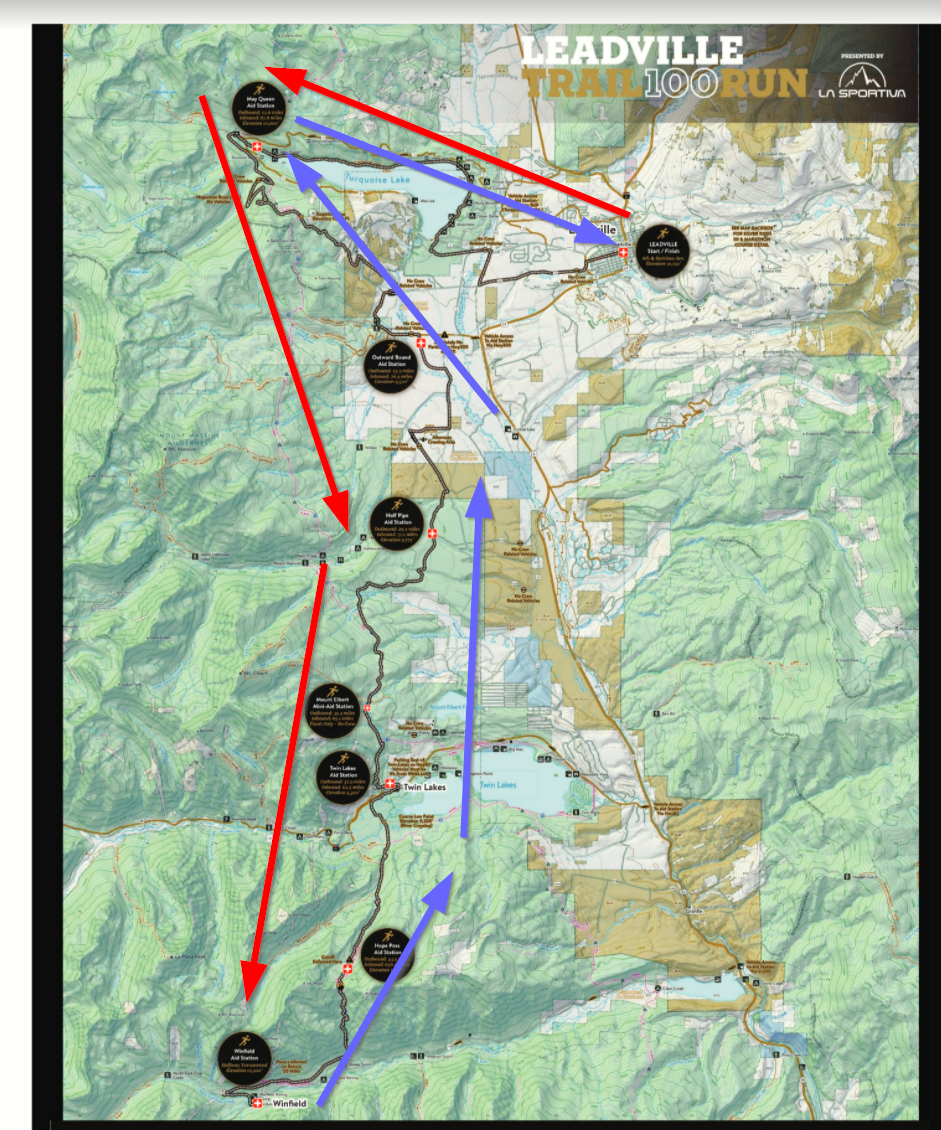

The course in 2019 was just over 100 miles (we tallied 100.7 miles) and is broken into 12 checkpoints/stations. The course is 50 miles in one direction (outbound) and then you backtrack the same course in reverse (inbound). Winfield is the 50 mile point and is where you can pick up pacers (which aren’t allowed on the first 50 miles).

Here were the stations and the time requirements for each station (if you don’t hit a time hack, they boot you off the course and you DNF).

Outbound

- 7:30am (3 hours 30 minutes) – May Queen: 12.6 miles

- 10:30am (6 hours 30 minutes) – Outward Bound: 23.5 miles (also referred to as the Fish Hatchery)

- 11:30am (7 hours 30 minutes) – Half Pipe: 29.3 miles

- 2:00pm (10 hours) – Twin Lakes: 37.9 miles

- 4:15pm (12 hours 15 minutes) – Hope Pass 43.5 miles

- 6:00pm (14 hours) – Winfield 50 miles

Inbound

- 10:00pm (18 hours) – Twin Lakes: 62.5 miles

- 1:15am (21 hours and 15 minutes) – Half Pipe: 71.1 miles

- 3:00am (23 hours) – Outward Bound: 76.9 miles

- 5:00am – Big Buckle sub 25-hour cutoff

- 6:30am (26 hours and 30 minutes) – May Queen: 87.8 miles

- 10:00am – Small Buckle sub 30-hour cutoff & Course cutoff

Aid stations are available at all the checkpoints and there are some additional ad-hoc and makeshift aid stations along the route, which provide basic hydration/nutrition and smiling faces.

Here is a map of the course:

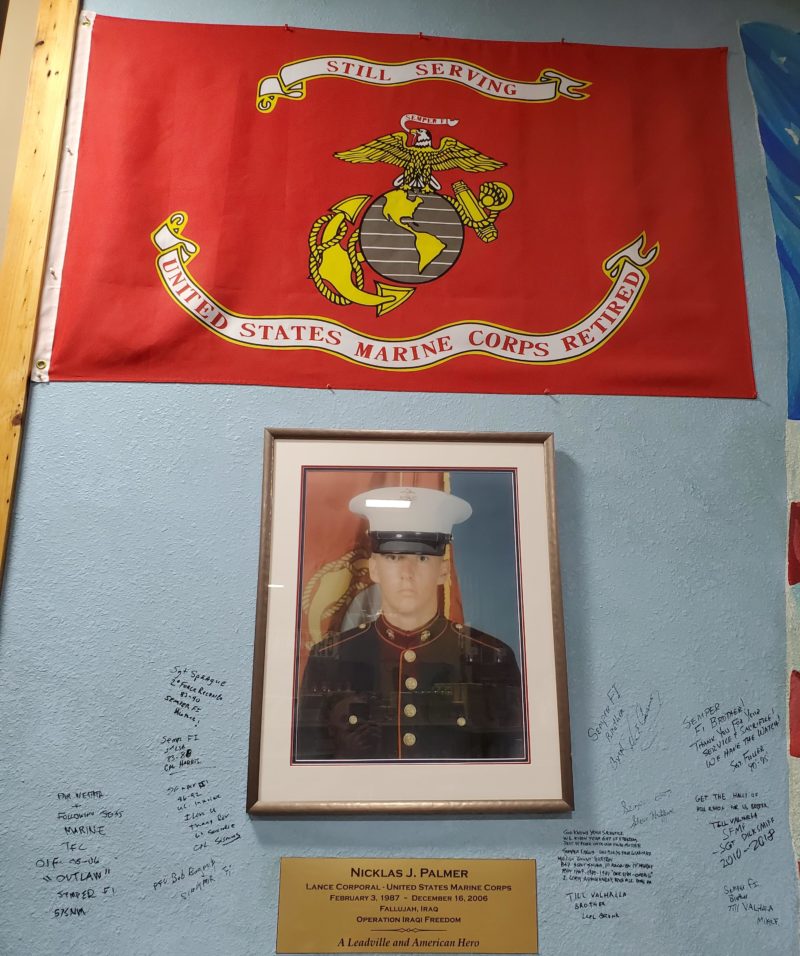

4:00am (Elapsed Race Time 00:00)

[josh] The gun goes off Zero Hour for the 2019 Leadville Trail 100 race. Debbie and I watch as 831 runners charge through the gate while the crowd whoops it up. The field is a sea of headlamps and somewhere in there are four runners from the CAF/Alpha Architect team: Amy, Pat, Ryan, and Wes. It will be at least 10 hours and 40 hard miles (for them) before we’re reunited. I catch a ride back to the house with Debbie. After a nap and breakfast, I sip coffee and chat nervously with Rod and Nicole, my fellow pacers. I feel my heart pounding in my neck and look to see my heart rate monitor reporting 105 beats per minute, about 55 higher than normal. This is distressing. Coming from sea level less than 24 hours prior, I knew that a race at 2 miles above sea level would be tough, now it was looking improbable. Don’t think, just do. [wes]: We hit a 0300 wake up the morning of. My mind was in a good place. Almost zen-like as if we were about to enter a combat situation and you knew you were more prepared than the enemy. The day prior, in the local hole-in-the-wall gas station, was a picture dedicated to a fallen Marine from the Leadville area, whom Pat Cleary served with while in Iraq. This was just the kind of motivation we needed to remind us that whatever pain this stupid event was going to throw at us, the fact we could feel pain meant we were still alive, and therefore still grateful for Marines like Nick Palmer.

Here are some pics from the start:

10:00am (Elapsed Race Time 06:00)

[wes]: The grind is underway. The first 6 hours on my end cover around 30 miles and plow through 3 checkpoints: Start to May Queen 1, to Fish Hatchery 1 (i.e., outward bound), to Half Pipe 1 (highlighted below).

Right out of the gate I immediately have issues with my hydration bladder. The suction valve is leaking, and my head is about to explode. Really? My water source isn’t working 5 minutes into the race? I improvise and solve the problem by positioning the value so it is pointed up and gravity can keep it from leaking. Good to go. My first opportunity to test out the primary way to finish the race — a relentlessly positive attitude. Along the way, Kirlin and I start bullsh#$ing about our race plans and how we are feeling. Our confidence is sky-high and we even contemplate how we may be able to finish in the top 10%. (ha. What a joke, looking back!) We immediately run into a fellow fintwitter — Mike Alfred — who gives us a shout out of the blue, freaking me out in the process. Mike would go on to crush the race and finish in less than 25 hours. Unbelievable.

After 5 or 6 miles of road running and battling crowds, things start to thin out a bit when we enter the path along Turquoise Lake. The runners all form a huge line along the single-track course that weaves around the lake. At the northwest edge of the lake is the “May Queen” aid station, which is 13.5 miles from the start. This is the first of the checkpoints/aid stations, spaced out along the 100-mile trail, which are designated areas for your crew to meet you with supplies, nutrition, and motivation. They are also important time checks: each station has a designated cut off that’s measuring your progress along the entire route. If you don’t make the aid station cut off time, you’re pulled out of the race, no matter how good you are feeling. This early in the race, I’m already stressed about the cutoffs – because of the traffic the pace along the path is pretty slow (12min/mile) and I’m getting concerned because I’m not hitting my time hacks, but there is nothing you can do on single track paths — passing really isn’t an option. But the slow pace is probably a good thing. The #1 piece of advice that 100-mile racers share is the mantra of “go slower than you think you should.” So while I’m worried that the pace is too slow, I am also aware that maybe this is a good way to manage my nerves and conserve energy.

We power through the May Queen Station and I’m feeling fresh. Doug Pugliese and Brandon Koepke hand off my trekking poles and some nutrition and I’m back at it in short order after inhaling 500 calories. I pound a beet-um and some Gu Roctane (my go-to source). The report from Doug/Brandon is that Ryan/Amy/Pat have all blown through the checkpoint already and the squad is looking strong. Awesome!

The next section is from May Queen 1 to the next aid station, Fish Hatchery 1/Outward Bound, which is a 10-mile stretch that essentially amounts to climbing up and down sugarloaf pass, which is roughly a 1k+ foot climb (see below). The views along the climb are magnificent and the temperatures are perfect for running (around 50 degrees!)

My motivation is high and the forest provides shade along the trail so I’m feeling great and my fellow runners are keeping me motivated, with some good light conversations along the way. On the hills, I take the opportunity to power walk and I’m jamming on my Leadville 100 playlist, which is a mix of everything from Enya to 2Pac.

I finally end up at the Half Pipe aid station, and I am destroyed physically. My biggest concern is my IT bands, which generally flare up at around mile 20-25 and shoot pain into my hamstrings and hip. Both of my IT bands are shot after coming off the pass. And we are only at 29 miles. But I know I am going to get to see my wife and kids at the Half Pipe station, which keeps me motivated. I’m going to finish this damn race because it’s pissing me off. I can also see Kirlin not far ahead. So now I have something to aim for and a conversation with Kirlin is always welcome.

Despite my IT band issues, I step off from the station after hydrating and pounding around 600 calories (grilled cheese sandwich, deltaG, and some GUs). A big mountain is checked off, and now it is just trails and beautiful landscapes for 10+ miles. I quickly catch up to Ryan who is having food issues and can’t keep calories down. Not a good sign at all, and terrible luck, but his mind is strong and he powers through the pain. I’m not that concerned for Ryan. He was a world-class endurance athlete in his younger days (rower) with a resting heart rate that is lower than the returns on value stocks the past 10 years (i.e., unimaginably low. :-) )

We grind together for about a mile and then I go into another gear since my body is feeling good for once and I want to take advantage of it while I can. Once I break from Ryan at this stage of the race I won’t see Ryan or Pat again. And I won’t see Amy again until we randomly meet along the way up Hope Pass the second time.

12:30 pm (Elapsed Race Time 8 hours 30 minutes)

[josh]: After watching the start, we catch a ride up to the Twin Lakes aid station. This is mile 38 in the race and it is the last checkpoint before runners go up and over Hope Pass, the 12,600 foot monster mountain pass that makes Leadville the beast that it is. Having arrived several hours earlier, Debbie is waiting for us with a tent, chairs, and provisions. This is home for next two hours, so I relax in the shade and take in the spectacle. Amy is the first of our runners to come through. She looks to be in great shape and after fuel and photos she was off to climb the beast. I know Wes won’t be far behind, so I walk up to the trail head and wait for him. At 12:38, he passes through the electronic check point, 82 minutes ahead of the cutoff. He’s in great shape and after a quick stop he too is off. Now, nearly 10 hours after I had originally woken, my day begins. As soon as Wes is out of sight, I grab my gear and head for the bus to Winfield aid station. Winfield is an old ghost town at the base of a few mountains. It also happens to be the half-way mark and turn around point for the race. To mitigate congestion, crew and pacers must take a bus from the Twin Lakes aid station. As I walk up the road away from Twin Lakes, the bus line unfurls a quarter-mile long in front of me. Dang, I should have left sooner. [wes]: The movement from Half Pipe 1 (mile 29) to Twin Lakes 1 (~mile 40) is physically challenging with some gradual elevation gains/losses, but I am in a flow state and my “mind callousing” has prevailed. The Goggins training method works.

This ~10-mile segment of the run starts with some open-air running alongside the Rocky Mountains and eventually weaves into a small mountain pass that takes you on a journey through an aspen forest (see Amy below). Mentally, this section is not terribly difficult, save a little heat/direct sun, and the terrain is pretty forgiving. (When I come back through these sections on the return trip back, my attitude changes — dramatically. Keep reading).

The one thing that sticks in my mind on this part of the course is that my emotions started to hit me in ways they have never done in the past. I had incredibly violent emotions of gratitude and gratefulness (at one point I started rattling off everyone who I appreciated in my life, talking out loud to an audience of nobody). And then I would start randomly shedding tears (I can’t even remember the last time I cried). I wasn’t sad or happy, but I was crying. Very odd. I also start chanting some Marine Corps cadences along the way, things I hadn’t thought about in a decade. The whole experience was confusing. I’ve never been one to experiment with psychedelic drugs, but my guess is that a cocktail of 40 miles of running/trekking mixed with a complete lack of oxygen thanks to the 10k+ elevation had recreated a similar experience. I was high as a kite.

Eventually, I touch down at Twin Lakes 1 and I am filled with joy. This will be the first time where I’ll take a break that lasts longer than 2 minutes. Our crew, led by my wife, Katie, is absolutely incredible. The whole squad is remarkable. Debbie/Josh/Doug all hook me up with my drop bag of gear and starts stuffing my face with chow, commanding me to eat. I follow their orders because I know they are 100% right. If you don’t eat at Leadville, you die.

When I see everyone I get a healthy dose of positive energy. The crew immediately shares the news that Amy came through looking great and that Ryan and Pat were not far behind me. Everyone is on track to have a chance to finish. I love it!

The Twin Lakes aid station is the biggest by far and is a key logistics waypoint before the runners tackle the double ascent of Hope Pass. Debbie is our crew chief at Twin Lakes and she has things squared away and prepared for all our racers. The scene at the Twin Lakes station is electric and feels like a mini-rock concert with people everywhere screaming and yelling. It’s great!

I spend 10 minutes at the station, change my shoes and pounding calories in preparation for the heart of the race — the trek up and down Hope Pass — 2x!

Luckily, my daughter provided me with some last minute motivation for the rest of the race.

And we’re off!

3:30pm (Elapsed Race Time 09:30)

[josh]: I hop off the bus in Winfield (50 mile point) and wait like a parent with overdue children. Not knowing how long the traverse should take, I hunker down in the shade and prepare my mind for the night ahead. Eventually, I’m joined by Rod and Nicole Heard and it dawns on me what a strange situation this is. Here I am sitting in a Ghost Town with two friends and hundreds of strangers, not quite sure if I will be on the trail for the next 12 hours or – if our runners hit failure before 50 miles – catching a ride back to Twin Lakes on a rickety school bus. After chatting for a bit, Rod, Nicole, and I agree that if the cutoff time passed, we’re going over Hope Pass on our own. We hadn’t come all this way for a school bus ride! [Wes] The first landmark past the Twin Lakes station is a series of water crossings, includeing the crossing of Lake Creek, a decent size river that is FREEZING cold, but feels incredible on tired feet/joints.

And of course, in classic Leadville 100 fashion, they make you climb it twice — go over the pass into Winfield, and then backtrack the trail you just finished. In total, you bag around 6k feet in elevation gain pretty quickly. If you can get through Hope Pass out — and back again — you have the race in the bag. Or so we are told.

Of course, because Hope Pass is a known pain point, our team did several training runs on the mountain before the race to get a sense for just how bad it would be. And it was bad, but it was also beautiful.

But training runs are one thing. The real thing is a bit different. In the race, you have hit the Hope Pass section 2 times AFTER bagging 40 miles. Sheesh.

I left the Twin Lakes station as a man possessed. I somehow triggered my deep-seated system 1 “warrior brain,” which is a somewhat demented headspace I developed while in the Marines. A mental state that I stuffed in the memory banks in hopes I’d never need it ever again in the civilian world. The crux of the race was in front of me and I needed to “kill” the mountain. I started up my music again (had to bag it around mile 30 because I wasn’t in the right headspace). I generally hit Enya on repeat when I am cruising along (yeah, say what you want, I know it is pathetic), but the mountain requires something different. Something downright gangsta. My preference is 2Pac, in particular, the song Ambitionz az a Ridah. I don’t even listen to the words, but the rhythm and beat are perfect. I would listen to that song on repeat for the next 6 hours.

I can’t even remember how long it took me to get to the makeshift aid station just below Hope Pass, often referred to as the “llama station” since a pack of llamas carries a bunch of food up there for racers to devour at 12k+ feet. All I know is that I went way too fast and smoked my legs. A strategic failure. The exact opposite strategy recommended by ultramarathoners who know what they are doing. Well, I’m not a professional ultramarathoner, and I just wanted to finish this G-d Da#@ race.

Along the way up and down Hope Pass, I passed a ton of people. (note: I had people after the race hit me up out of the blue in a sea of people and say, “Hey, were you that crazy dude with the trekking poles going up Hope Pass way too fast?” Interpreted differently, “hey, are the idiot that smoked their legs up Hope Pass, essentially ignoring the advice of every expert on the planet”). I’m sure I was going too fast but I knew I had to get to Winfield and back to Twin Lakes as fast as possible or I wasn’t going to finish the race. I also wanted to catch David Goggins. I knew he was about an hour ahead of me according to the Twin Lakes crew and my mentality was such that I wanted to pass him (even though any rational thought would suggest that to be impossible). I powered up the mountain and ended up passing Goggins — but he was going in the other direction, already on his way back to the finish, while I was still on my way out to the halfway point at Winfield –LOL! So technically I “passed” Goggins. I gave Goggins a military grunt as he huffed and puffed up the mountain while I cruised passed him going downhill. Goggins had me inspired. I always thought he was superman, but seeing him struggle up the mountain, and show his humanity, helped me understand that he feels pain like everyone — he simply chooses to ignore it and fight through. No magic tricks. No pixie dust. Pure grind. Amazing.

4:50 pm (Elapsed Race Time 12:50)

[josh]: I spy Wes coming off the trail and he’s moving strong. As we’re walking to the aid station, I do a quick systems check with Wes. His knees are screaming in pain, but his will is strong. At 1702 Wes is officially through the checkpoint. Now it’s go time! 50 miles to go. As I fill up his hydration pack, it hits me, “this is really happening.” Due to single track trail and bidirectional traffic, it’s slow going from Winfield to the base of Hope Pass. Along the way we pass Ryan and shout encouragement. He’s tight on time but he’s still in the game and looking strong. At one point we trek past a guy passed out on a rock. There are already a few people attending to him, so we keep moving. With a 20% average grade, Hope Pass is about as steep as it gets without climbing gear. At its base, it is about 10,000 feet above sea level. At 1812 we start our ascent. Wes is a man on a mission and it’s all I can do to keep up with him. Fourteen minutes later, we pass a log and he says “we’re a third of the way up.” My heart rate monitor reads 190, about 10 beats per minute past my redline. With fresh legs and fresh lungs, it’s all I can do to keep up with the human mountain goat. From here things only got steeper. With my lungs burning and my heart racing I realized my wife was right — I’m an idiot. I keep pushing on to avoid the dreaded spousal “I told you so.” At thirty-five minutes into our ascent, we pass another log and Wes called out “two thirds.” Around here the trail narrows and the switchbacks start — making passing impossible. As we climb the last 800 feet in a conga line of runners, I’m able to catch a breath and recover a bit. For a brief moment, I’m reminded of the old film reels of the Klondike Gold Rush. The line of people on this section of the trail is so long that passing would not be worth the energy expended. [wes]: Eventually I found myself dead on arrival in Winfield. Here is where I would link up with Josh Russell, my pacer for the last 50 miles, which is backtracking the first 50 miles. Winfield is a great moment for me. I take a quick break and link up with Josh, which is a huge relief. Being solo for 50 miles is a mental drag and having a partner in crime on the back half of the race is a huge benefit. We saddle up our gear for the back 50 and the pain cave is only beginning. Next up, an insanely steep climb back up and over Hope Pass. Oh boy!

Here is a pic of the pacers waiting patiently at the 50 mile mark to pick up their runners.

7:28pm (Elapsed Race Time 13:28)

[josh]: As we summit Hope Pass I take in the view without breaking stride. All in, we passed 78 people on this leg (more than 10% of the runners that made it to Winfield)! After a brief stop at the Hope Pass aid station, we start our descent. We’re in the trees as dusk falls and are quickly swallowed by darkness. Our descent is slow and methodical to prevent more damage to Wes’ battered knees. [wes]: As I head up Hope Pass for the second time today, my knees and IT bands are shot at this point and every step/fall reminds me that I am still alive. Conga lines form in the steeper sections and the conversations have all but ceased. Everyone is in their own personal torture chamber and nobody has the energy for a conversation. We have all entered survival mode. Meditation at its best!

9:20pm (Elapsed Race Time 17:19)

[josh]: The trek into Twin Lakes is a slow grind and mostly uneventful. At one point we wade across an ice-cold creek. I manage to trip over my own feet and end up waist deep. In the process, I splash water all down Wes’ back. He takes it in stride, but that’s got to be a major annoyance nearly 16 hours into a race.We arrive at the Twin Lakes aid station – the 60-mile mark of the race – forty minutes before the cutoff time. This checkpoint is one of the harder time cutoffs to make, so it is a big relief that I make it through with time to spare. We’re greeted warmly by our crew who get us changed, refueled, and sends us on our way. It dawns on me that the crew job is a thankless task. You get up early to beat the crowds and save a space, set up camp, and then you stand watch… for hours. All this time the crew is alert and ready to jump into action as soon as your runner comes. When they finally show up, you’ve got to change their socks, fill their canteens, shove their pockets full of snacks, listen to them whine, and get them moving on the double. It’s a thankless task. As a runner/pacer, you know what you need because you’ve been thinking about it for hours. You plan your movement in and out of the gate. You’ve got a mental checklist “socks, shirt, hat, hydration, bagel, energy bar.” As it turns out, slogging it out for hours on the trail, barely stopping to pee, isn’t breeding grounds for manners. When you finally get to your crew, your list turns into “I need my bag! Quick fill this thing! I don’t care whatever you’ve got! Shit, where’s my hat? And that thing, give me that thing! Okay, see you later.” In short, to the Alpha Architect crew, I apologize for anything I said and all of the “thank yous” I didn’t say. You guys are awesome and we wouldn’t have made it without you.

After that fact, we would learn that Patrick made it past Twin Lakes and on to Hope Pass, but he would eventually get tangled up with the time limits and exited the course. He put in an incredible effort and eventually made it back to Twin Lakes to meet up with our crew and get some well-deserved rest.

Ryan Kirlin had some major drama with checkpoint time limits on Hope Pass. I eventually learned that he managed to make the cutoff time at Winfield by a whisker and was literally going to need to sprint off the mountain if he hoped to make it back to the second Twin Lakes stop in order to make the cutoff. It turns out that Ryan did end up sprinting down the mountain, averaging a 6:30 mile pace (which is INSANE, especially after 60 miles and in the black of night!) only to miss the Twin Lakes cutoff by less than 1 minute!

Yes, ONE MINUTE.

But rules are rules, and the race coordinators booted him off the course. Sadly, for two of our teammates, Twin Lakes was the end of the Leadville journey. But Amy and I were still on the hunt.

9:34 pm (Elapsed Race Time 17:34)

[josh] As we depart Twin Lakes, I note that what felt like a five minute stop was really fifteen. We’re now floating less than a half-hour ahead of the cutoffs. We need to make time on the trail and we can’t afford to rest at every oasis. The climb out of Twin Lakes is steep, but this is our strong suit. We make quick work of our second summit and gain another 20 places or so. We climb past Barefoot Ted McDonald (of Born To Run fame) and someone blaring old school funk. Things get weird in the middle of the night. On top of the hill were treated to an epic moonrise reflecting over the lake. I try hard to be present and take in the scene. There’s the moon rise over a mountain lake, the stars, hundreds of maniacal souls tromping toward an old mining town, and Jungle Boogie. This may be one of the strangest nights of my life (and I can’t even blame it on beer). By now we’re in the trees and the trail is dark. Every now and then I hear Wes stumble and then a soft slow, “oh yeah.” Not “oh yeah, this is amazing” more like “oh yeah, I just slammed my shin into a trailer hitch.” I realize that headlamps projecting down don’t cast shadows and make the terrain hard to read. After a bit of experimentation, I figure out that I can hold a headlamp down by my hip and cast shadows on the rocks and potholes in the trail ahead. And thus I found my primary mission for the next seven hours. [wes]: Okay, I’ll be honest. I am 60 miles into this thing and I’ve become numb to the pain. I am freezing cold and delirious. I think Goggins is a real a##hole and the whole mind over matter thing is a steaming crock of sh#$. My feet have hotspots everywhere and I know a few blisters have already burst because every step feels a little squishy. That said, there is a 0% chance I’m going to quit at this stage, but there is a >0% chance that I could actually die on the course.We are now on the final stretch back home. 40 miles of pure grind. Head down. No stopping. Wake me up when this nightmare is over. (final section is mapped out below).

As we leave Twin Lakes, my only thoughts revolve around how I am going to survive this fu#$en course. But I draw strength from my time in the Service and feel a strong sense of duty to represent their sacrifices and maintain the Marine brand of “Pain is weakness leaving the body.” The only thing I can grasp onto is not embarrassing the Marines and meeting one of my Marines buddies and listening to them say, “Dude. You are such a P___Y.” Without that old-fashioned, and totally not WOKE motivation, I’m quitting at this stage.

I get my body out of the lawn chair, thank Josh for dealing with my pathetic a$$, and prepare to step off for the worst 12+ hours of my life.

12:14am (Elapsed Race Time: 20 hours 14 minutes)

[josh]: A new day, a new checkpoint. We’ve picked up a decent pace and made it into the Half Pipe aid station an hour before the cutoff. On the flats, we’re making somewhere between 17 and 18 minutes per mile. Neither of us really know our pace because Wes’ fancy running watch died an hour ago. I’ve got a cheapo running watch that should last for the duration of the race, so I turn its GPS on. There’s no crew at Half Pipe, so we move quickly and get back on the trail. I did a quick calculation and figured that we were in good shape. We’ve still got to go 29 miles and climb one last big hill, but we’ve got over nine and a half hours left on the clock. The trail here is mostly flat and we put in a good effort. We’re clipping along at about 17 minutes per mile (well ahead of our 3 mph minimum) when my cheapo running watch stops responding. This is a terribly inconvenient time to have a double gear failure. But, I spent most of my life walking without technical aids, so I’m confident that we can work this out. At one point we pass a gravel parking lot about a half-mile long and there is a Leadville 100 Tailgate party going. There’s music, festive lights, and what looks to be a lot of Kool Aid (what else would you drink in an empty parking lot in the wee hours of the morning?). I guess the drive-in theater is closed this weekend. The air is dry at this altitude, so you don’t really notice the cold creep in. It’s the middle of the night and the temperature has dropped into the 40s. Every time we pass near water, the humidity spikes and I’m reminded that I’m still wearing shorts. We’ve got crew at the next aid station and I’m planning on adding a base layer and changing my shoes. Not wanting to waste time, I sprint the last half mile in. [wes]: On the way out of Twin Lakes I have little memory of anything save the incredible moonlit view of Twin Lakes — which was mesmerizing. I am simply one foot after the other and relying on Josh’s chatter to keep me going. I keep thinking of insane tales of survival and wondering if this is how they felt. Josh is telling me incredible stories, and I’m listening intently, but not recording anything into memory. All mental energy is aimed at finishing. Must. Finish. This. Fu#$ing. Race.1:54am (Elapsed Race Time: 21 hours 54 minutes)

[josh]: Katie and CJ are there waiting for us at the Fish Hatchery (also called Outward Bound). This is a huge help because Katie can expedite for Wes and get him moving again. I throw on some long johns, refuel, rehydrate, and then I sprint to catch up to Wes. As I’m tearing out of the Aid Station, a group of people starts cheering. Then it dawns on me that we’re approaching the 22-hour mark. No one this far back in the pack is sprinting, that’s for the professional runners that have already finished. For a brief moment, I’m the fastest person in the Leadville 100 (or so I tell myself). Wes is moving at a good clip and it takes me the better part of a mile to catch him. Sugarloaf Pass looms ahead, though we can’t see the 1500 foot monolith it in the dark. A Leadville veteran had told me that we would pass two false summits and then top out 15 minutes later at the Hippie Camp. It was said that that the Hippie Camp was a psychedelic array of glow sticks and that it had a strange skunky smell (but so does much of Colorado). I was also warned not to eat or drink any food offered there. Wes has been on the trail for nearly a day now and the fire he had climbing Hope Pass is slowly turning to ash. The ascent on Sugarloaf Pass is slow and steady. Without knowing our speed, I focus on keeping a pace that is just a bit uncomfortable. He doesn’t protest, so I keep pushing. With over twenty miles to go, a 1 minute per mile pace differential is meaningful. I use my headlamp to scout the path ahead and use the light in my hand to guide Wes to the smoothest parts of the trail. I daydream that I’m guiding a lost pilot to the deck of a carrier on an overcast night. In reality, I’m sitting shotgun in the world’s slowest rally car race. “Left… left… now right… no, stay there,” I say as I pass the time. We pass two false summits. I can see the chem lights that mark the trail extending up out of sight. I’m elated that we’re almost done with this dreaded hill. We pass two more false summits and I can see chem lights twenty degrees above us still. I realize that the Leadville veteran was just hazing me. Sometime later we hear a horn. Nothing musical, more like the mating call of a sick moose. Within minutes, the terrain flattens out and the trail is awash with color. Either we’ve made the Hippie Camp or the hypoxia is starting to do permanent damage. As we approach the camp, the mating call sounds to announce our arrival. I’m greeted by a native and lose sight of Wes for a moment. I turn around and see him grabbing a drink of some sort. I forgot to pass on the warning from the Leadville veteran –c’est la vie. What a long strange trip it’s been. Onward we go into the night. This leg of the trip was supposed to be eleven miles. We’ve been night flying by stick and rudder into a headwind. I have no idea how far we’ve gone. Derelict in my pacer duties, the only thing I can do is try to keep a decent tempo as we descend toward May Queen, the penultimate checkpoint.

The one surprise throughout this section was the difficulty of climbing up (and down) Sugarloaf Pass. I believe this relatively small section of the race was harder than going up and down Hope Pass 2x.

If you are at this stage of the race, be ready to dig deep. If you make it, there is no way you won’t finish.

5:50am (Elapsed Time 25:50)

5:50am (Elapsed Time: 25 hours 50 minutes)

[josh]: We were 65 minutes ahead of the cutoff at Outward bound. As we drift into May Queen, I realize that we’ve given up 25 minutes of our lead. We now have 250 minutes to cover somewhere between 12.6 and 13.5 miles. There is uncertainty around this because the official race guide has both distances listed. This may seem minor, but 13.5 miles vs 12.6 miles means a minimum pace of 18:30 vs 20:00 minutes per mile. A quick calculation tells me that the last leg took us over 21:30 minutes per mile! The prospect of not finishing after twenty-six hours on the trail is terrifying. Our original crew plan was for me to hand off the baton to Katie for this last leg, but I think it would be better if we both go. Over the past 13 hours, Wes and I have established a decent rapport (I tell him to speed up, he grunts and ignores me) and I think I can keep him on schedule. But I need Katie’s help monitoring Wes’ vitals so that I can focus on the pace. Confession: not all of my motives are altruistic (I’m a sick man). Picture this as Round 14, Apollo Creed is punishing Rocky. The challenger’s nose is broken, his eyes are swollen, and his feet are unsteady — but he’s still fighting. I don’t know how the movie ends, but I’ve got to watch round 15. That and I’d like to make an even 50 miles here. As we near May Queen, I run ahead to inform Doug and Katie of the altered plans. Katie intercepts Wes and keeps him moving up the trail while I get provisions at the aid station. I sprint and catch up with them in a matter of minutes. In my haste, I make an error and forget to take my electrolyte pills. Without these, my body chemistry gets out of whack, I can’t eat without getting sick, and I will eventually bonk. For the second time this race, the twilight gives way to sunlight. As we hike along the bank of Turquoise Lake, I’m reminded of the beauty that surrounds us. The soft sandy trail is welcoming after hours on hard-packed fire roads. I attempt to eat the last half of a bagel that I’ve been carrying since Outward Bound, but I’m unable to swallow. Wes is in the same predicament, so Katie keeps pumping fluids into him. I still have no idea how fast we are going, I only know that the clock is moving against us. With my uncertainty, I’m careful to manage information here. I don’t want Wes to think he has time to spare and I also don’t want him to think that our task is impossible. In his state, both could lead to ruin. At this point, life is simply one step at a time — the faster, the better. “Wes, give me another five percent,” I beg. He does his best and we keep the pain train rolling. About halfway around the lake, I get a cell signal and I’m able to get an accurate pace. We’re on flat ground and making better than 18 minutes per mile. I estimate that we have about a 12-minute cushion and I relay this to the team. We’re still eight or nine miles out, so this translates to about 90 seconds per mile of padding. By the time we get off the lake and start heading for downtown Leadville, the sun is fierce. Wes grits his teeth as we slowly descend a steep rocky hill under some power lines. At this point, his knees and feet are wasted, he hasn’t eaten in hours and hasn’t slept in days. At the bottom of the hill, we turn due west and start ascending again — now we’re heading right into the sun. It’s round 15 and Rocky is fighting for his life. [wes]: I have no real comment here except to say that if Josh and Katie weren’t with me on this final leg I would have definitely not finished. I had gone bonkers, my mind was failing me and at mile 87 I had only one speed– slow. And I was pissed off at the world. Josh was able to keep the pace going at a rate that was much faster than I felt comfortable with but it was necessary if I was going to finish this thing under the 30-hour belt buckle barrier. Katie was there to tell me stories that took my mind off my pain. Word of advice: If you decide to take on this race, ensure that you have pacers on the final sections or your ability to cross the finish line will be greatly diminished. Also, bring warm clothes. Even though it was probably 70 degrees along this part of the course, I had my beanie (toque for you Canadian weirdos out there!) and down jacket on and still felt cold! Weird things happen when your nutrition gets out of wack.

8:10am (Elapsed Time 28:10)

[josh]: Google Maps tells me we’re four miles out and the clock tells me we have just under two hours before our cut off. That should give us a thirty or forty-minute cushion. Four miles in two hours doesn’t sound like much – but remember we’ve already gone 96 miles!! Moving up the hill, we’re out of the trees and none of us have any sun protection. I never had time to strip off my long johns and I’m heating up quickly. The heat, the electrolyte imbalance, and the lack of food have me feeling pretty sick. Wes is in worse shape, so I keep my discomfort to myself. We’ve been on dirt trails and fire roads for most of the night and I’ve aspirated a whole lot of dust. My throat and lungs are coated with it. We’re climbing again for the first time in four hours and as my breathing deepens, I start coughing up thick mud. This of course compounds my other issues and I start dry heaving. This is a critical juncture, I know that if I stop to vomit, Wes will stop too. Years of diving have given me how to control my diaphragm. Deep into a breath-hold, your lungs burn from carbon dioxide. Your diaphragm involuntarily contracts, trying to expel the toxic gas building therein. The problem is that if you’re thirty feet (or even three feet) down, this survival instinct will cause you to drown. So you learn to remain calm, control your diaphragm, and go on about your business. After a few deep breaths, I regain control of myself, and the pain train rolls on. After a mile of climbing, were at the top of the hill. Wes asks “how far” and I report back “three miles”. This puts us an hour out and he seems relieved. A hundred yards later, we detour from the main road onto a dirt trail that Google is unaware of. At this stage in the race, little set backs are devastating. Wes asks “how far” and for the second time I report back “four miles.” However, this is just a guess. I really don’t know because we’re on an unknown road moving away from our destination. The good news is we’ve still got ninety minutes and it looks like we’re going to get everything we paid for. We detour about a half-mile to another paved road and make our final assault on Leadville. When you look at an elevation profile for this race, you see that you climb over three mountains (in each direction). What’s easy to miss is that in the last three miles, you also gain 500 feet in elevation. Just when you start dreaming of the finish line, you round a corner and you’re faced with another monster hill. On our way up the hill we’re joined by Tim Maguire. Tim is part of the CAF family, he’s a former Leadville runner, and he’s a long-time friend of Wes. He gives much-needed encouragement as we grind up the hill. “Just one more mile,” says Tim as we near the crest of the hill. I check my watch and we’re forty minutes out. I relax for the first time in hours. I know that we could crawl the rest of the way if needed. Near the top of the hill a spectator shouts, “you’re almost there only a mile and a half left!” “Hey! can’t you lie just a little?” Tim shouts back. At this point, it doesn’t matter, we’re on the edge of town and we can hear the crowd. We turn onto 6th Street and a hundred yards later, we’re looking at the finish line a half-mile downhill. [wes]: Mentally, the final stretch is tough for me (but not as bad as Sugarloaf up/down). I feel like the little kid in the back of the car on a long road trip that keeps asking his dad, “Are we there yet? Are we there yet?” I try to keep my composure as best I can but every time I ask Josh “are we there yet” he tells me 3 miles. I ask him 5 minutes later and now we are “4 miles out.” My system 1 monkey brain starts to creep up on me and I internally start battling with my system 2 composed brain. System 1 says, “Dude, Josh is screwing with you. What an a$$hole. Don’t you hate this guy??? Fu#$ that guy.” But my system 2, rational brain fights back, “Hey System 1, Josh has been dragging your a## along this path for 45 fricking miles and all he’s done is pour his heart and soul into helping us finish this thing. STFU system 1.” The good news is my internal brain wars is also helping me pass time, which seems to move at a snail’s pace.Eventually we are a few miles out. Seeing Tim Maguire really cheers me up. I’m obviously happy to see Tim’s smiling face, but it also signals that we are actually close to finishing this insane race!!!

9:44am (Elapsed Time 29:44)

[josh] For the last half-mile I’m lost inside my head, trying to process what I’ve just experienced. I look over and see that Wes’ kids have joined us and it strikes a nerve. They’ll never know the details of the past thirty hours — the pain, the anguish, the grit, and the glory. All of this to complete an event that is unknown beyond a fringe group of fanatics. What they did see is that success comes from showing up, putting in the work, and taking one step at a time. They got to see that achieving your goals takes sacrifice, disciple, and the support of your tribe. Wes crossed the finish line of the 2019 Leadville Trail 100 at twenty-nine hours, forty-four minutes, and thirteen seconds and thus became a Leadville finisher. Rocky made it the whole 15 rounds; He went the distance!

I ended up crossing the line in an ugly fashion. Mission accomplished.

Right after I passed the finish line, we had another great moment: my sister-in-law was right behind me. After almost enduring a “Kirlin moment” at mile 87, barely making the time cut-off, Amy came back with a vengeance. (Can you imagine getting booted off the course at mile 87???)

Amy finished a few minutes behind me and crossed the finish line with her spirits high and her head held high. Leadville beat me; Amy beat Leadville! I was so proud of her I shed a few tears.

Post Race

[wes]: After finishing I immediately sought medical help. My knees were smoked but I figured they would heal over time. But I knew something was wrong with my feet, in particular. Turns out I was right. I had layers upon layers of blisters. Within a few days all of my toenails ceased to exist. My feet got an opportunity to have a new lease on life. Lesson learned for me: take a few minutes at an aid station and doctor your feet, dumba##.

But the good news post race is I had my comrades to help me through the ordeal. My crew literally carried me to the car. I was so exhausted I didn’t even make it to the ceremony to pick up my hard-earned medal. At that point, “things” weren’t interesting to me.

Final Thoughts

[Josh] It took me a few days to decompress and unpack everything I saw at Leadville. Even now, I’m still trying to figure out what compels otherwise rational people to join in these shenanigans. Outside of the crazy trail running community, there is no fame and notoriety associated with Leadville. Most people have never heard of it and react with a twinge of disdain when you explain it to them. Only a handful of professional ultramarathoners make money off these deeds. On the contrary, competing comes at great expense, both financially and socially. I think most that undertake such endeavors are trying to find (or surpass)their limits. They seek that master that which is unknown and uncomfortable. Perhaps this gives them a greater understanding of other parts of their lives. It is only after the storm that one can truly appreciate a calm day. No matter the eventual outcome, my hat is off to anyone with the guts to run through that starting line. Leadville is one of the most bizarre and inspiring events I’ve been a party to. I hope to see it again some day. [wes] Participating in the Leadville 100 was by far the most challenging thing I have ever done — way worse than anything I ever faced in the Marines and even worse than battling with Eugene Fama on my PhD dissertation (LOL). After the race, I asked Doug Pugliese to videotape me post-event so I could tell my future self that I would never participate in a 100-mile race ever again. You never know – with enough time there is a risk that my brain forgets the pain. Best to codify it upfront in the form of a video!My main takeaway from Leadville is that you really can deal with a lot more pain and anguish than you probably thought. I also appreciate the fact that I reached a state of “enlightenment,” or extreme self-awareness, during the experience. My life had changed, forever. I’m not even sure what the monks even mean when they talk about these states of being, but I think I finally understand, at least a little bit, of what they might be talking about. I came away from the adventure with a whole new level of self-awareness, humility, and an incredibly deep sense of gratitude for my friends, family, and colleagues. I’ll leave you with an augmented “acknowledgment” line I put in my first book, “Embedded,” which outlines my time living and fighting with an Iraqi battalion in Haditha, Iraq.

Here is the original from Embedded:

To the soldiers of the Iraqi Army, who taught me that winning isn’t everything; but friends, family, and honor are.

And here is my augmented version for Leadville:

To the soldiers of the Iraqi Army, To the Leadville 100 Trail run, who taught me that winning isn’t everything; but friends, family, and honor are.

References[+]

| ↑1 | A huge shout out to Katie Gray for editing this post. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I asked a few maniacs like Corey Hoffstein as well, but they were more rational and all of them rejected my offer. |

| ↑3 | There is a funny story I heard on some podcast where apparently Tommy Moe (the famous skier with unbelievable endurance from climbing up and down ski hills) attempted — and failed — do perform a “couch” LT100 ultramarathon. |

| ↑4 | I recommend the “science of ultra” podcast. Think of it as the Alpha Architect of financial research where the host brings on PhDs and talks about the latest research on human biology as it relates to ultra-endurance sports |

| ↑5 | Michael Pollen probably has the best advice: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” But who knows. |

| ↑6 | Note: I listen to music where I can’t understand the words and my mind wanders. I listen to the same song on repeat. It gets me in a flow state. For me, that is Enya’s Orinoco Flow and Caribbean Blue. Don’t ask me why. |

| ↑7 | I’ve tried to erase the event from my memory banks because it causes me pain to even think about the event (LOL!). And I’ve sat on Josh’s write-up for almost a year now. I figured it was time to put it out there in the hopes that this guide/conversation might help someone else. |

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.