Momentum is the tendency for assets that have performed well (poorly) in the recent past to continue to perform well (poorly) in the future, at least for a short period of time. Initial research on momentum was published by Narasimhan Jegadeesh and Sheridan Titman, authors of the 1993 study “Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency.” In “Your Complete Guide to Factor-Based Investing” Andy Berkin and I presented the evidence demonstrating that momentum, both cross-sectional (or relative) momentum and time-series (or absolute, trend following) momentum not only increases the explanatory power of asset pricing models while providing (historically) a premium, but that the premium has been persistent across time and economic regimes, has been pervasive around the globe and across asset classes, is robust to various formation and holding periods, has intuitive behavioral-based explanations for its existence (combined with limits to arbitrage which prevent sophisticated investors from correcting anomalies), and is implementable (survives trading costs using patient trading strategies).

Research into momentum continues to demonstrate its persistence and pervasiveness, in, as well as across, factors. Recent papers have focused on trying to identify ways to improve the performance of momentum strategies.

Improving on Trend Following Strategies

- The 2015 study “Momentum Has Its Moments”, found that momentum strategies can be improved on by scaling for volatility—targeting a specific level of volatility, reducing (increasing) exposure when volatility is high (low).

- The 2016 study “Idiosyncratic Momentum: U.S. and International Evidence” found that results could be improved, reducing the risk of momentum strategies, by removing the return component due to market beta. (summary here).

- The 2019 study “Extreme Absolute Strength of Stocks and Performance of Momentum Strategies,” found that eliminating stocks with the most extreme past returns from the eligible universe significantly reduced the volatility of portfolios while modestly increasing the average return in most cases, improving the risk-adjusted-performance. Doing so also alleviated the problem of momentum crashes and rendered momentum strategies profitable in the post-2000 era, a period during which momentum appeared to have vanished (due to momentum’s crash in April 2009). (summary here).

- The 2020 study “Opposites Attract: Combining Alpha Momentum and Alpha Reversal in International Equity Markets,” found that an integrated investment approach that combines the trading strategies of momentum and reversal is a superior strategy than either individually. (summary here)

The most recent attempt to improve on momentum strategies comes from Ashish Garg, Christian L. Goulding, Campbell R. Harvey, and Michele G. Mazzoleni , authors of the June 2020 study “Breaking Bad Trends.” They begin by noting that going long during sustained bull markets—or short during sustained bear markets—tends to be a good bet under such a strategy. However, trends eventually break down and reverse direction (called either corrections or rebounds). At and after these breaks trend following tends to place bad bets because trailing returns can reflect an older, inactive trend direction. “Faster trend signals (e.g., only a few months of trailing returns), rather than solving the problem, increase the tendency of placing bad bets because faster signals often reflect noise instead of a true turn in trend.” They called this the “Achilles heel” of trend investing. They attempted to find a way to mitigate the negative impact of breaks, or turning points—defining a turning point for an asset as a month in which its slow (longer lookback horizon) and fast (shorter lookback horizon) momentum signals differ in their indications to buy or sell. They sought to determine if these turning points were informative (predictive) of future returns.

To accomplish that objective, the authors partitioned an asset’s return history into four observable phases—Bull (slow and fast signals both +), Correction (slow signal +/fast signal -), Bear (slow and fast signals both -), and Rebound (slow signal -/fast signal +). When the signals agree, the dynamic strategy is the same as the static strategy. When the signals disagreed, they observed the historical evidence to determine if the fast signal was informative of future returns or not. They did this for each of the 55 individual assets in their database. They then used this information to specify an implementable dynamic trend-following strategy that adjusts the weight it assigns to slow and fast time-series momentum signals after observing market breaks (Corrections or Rebounds). That different markets behave differently is an interesting idea.

They explained:

“We say that an asset is at a turning point in month m if the signs of its slow and fast signals disagree. The basic idea is that if the average return over a shorter period is pointing in a different direction than the average return over a longer period (say, up versus down), then the market may have encountered a break in trend (say, from downtrend to uptrend). If a trend break has indeed occurred, then slower signals prescribe bad bets (e.g. shorting the market based on an older downward trend when the market is recently trending up). On the other hand, if disagreements reflect noise in fast signals rather than true trend breaks, then faster signals prescribe bad bets.”

Their dynamic strategy works in the following intuitive manner. If historical returns tend to be positive after Corrections (when the slow strategy goes long and the fast strategy goes short), then the dynamic strategy tilts away from the FAST signal. If historical returns tend to be positive after Rebounds (when the slow strategy goes short and the fast strategy goes long), then the dynamic strategy tilts toward FAST. If historical returns are negative after such states, then the direction of the tilt reverses. If the estimate is noisy, then there is shrinkage to a no-information signal. Their “framework supports dynamic blending of two time-series momentum strategies having slow and fast momentum signals.”

Their data sample included 55 futures, forwards, and swaps markets across four major asset classes: 12 equity indices, 10 bond markets, 24 commodities, and 9 currency pairs. Their sample begins in 1971 for some assets, adding each asset when its return data become available through 2019. Their time series of returns is based on holding the front-month contract (or 1-month forward or 10-year swap) and swapping to a new front contract as its expiration date approaches. Their slow signal is a fixed lookback window size of 12 months of prior returns and goes long one unit if the trailing 12-month return is positive; otherwise, it goes short one unit. The fast signal is the average of the prior 2 months of returns.

Following is a summary of their findings:

- As we would intuitively expect, there is a negative relationship between the number of turning points that an asset experiences and the risk-adjusted performance of its 12-month trend-following strategy. This holds across a diverse collection of assets from different asset classes and also carries over to multi-asset portfolios of trend-following strategies.

- For a multi-asset trend-following portfolio normalized to have 10% annualized volatility over the last 30 years, a one-standard-deviation increase in the average number of breaking points per year (+0.45) is associated with a decrease of approximately 9.2 percentage points in its annual portfolio return.

- Turning points and return volatility are uncorrelated—the number of turning points per asset per year is approximately uncorrelated with return volatility: 0.02 correlation. High or low volatility can appear during periods of sustained uptrend or downtrend (bull or bear markets) as well as at and after turning points.

- For assets with six or more turning points within a year, median returns to static trend following are negative. For assets with 8 or more turning points within a year, the vast majority of returns to static trend following are negative with annualized Sharpe ratios below −1.0 on average across assets.

- The number of breaking points helps explain the deterioration of trend-following performance in more recent years (as discussed in the 2019 study “You Can’t Always Trend When You Want”- Summary)— six of the most recent 10 years are in the top one-third over the last 30 years when ranked by the highest-to-lowest average number of turning points. An increase in turning points means a decrease in sustained periods of a trend.

- Trend-following strategies that react dynamically to asset turning points improve the performance of multi-asset trend-following portfolios, especially in months after asset turning points, which have become more frequent in recent years.

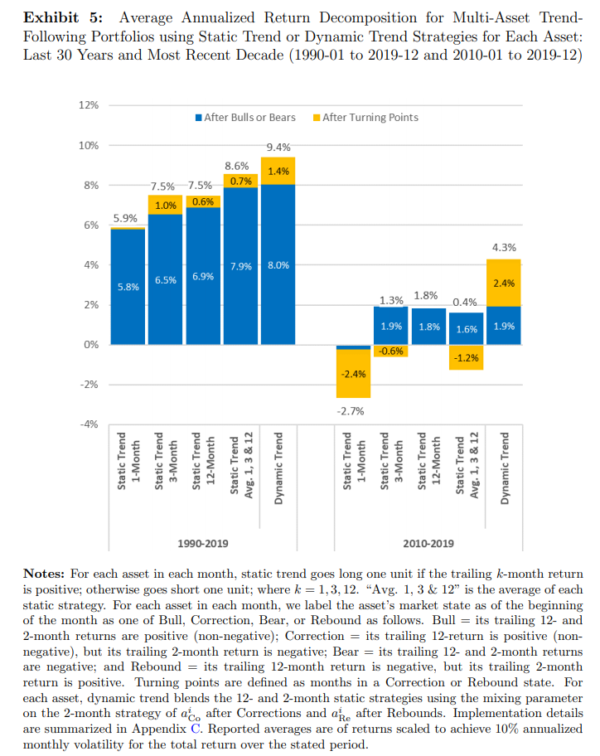

- Multi-asset static trend generates approximately 7.5% annualized average return over the 30-year evaluation period, yet only 1.8% in the most recent decade. Dynamic trend generates a 4.3% average return in the recent decade, which is more than double the 1.8% generated by the static trend, and the bulk of those gains are from returns harvested after turning points.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

While the results are both intuitive and impressive, the following cautions are worth noting.

- The authors didn’t provide any data showing the statistical significance of their findings. Thus, we cannot make any observations about its significance.

- They allocated equal weight to each asset’s value within its asset class and equal weight to each asset class across the four asset classes. This leads to the results being dominated by commodities and equities. Thus, we don’t know if the results are truly pervasive. And we don’t know if the results are robust to value weighting.

- As if almost always the case, we don’t know how different strategies they tried, and perhaps failed with, before “uncovering” one that worked.

- And finally, the period of 30 years is not that long.

Summary

The dynamic trend strategy studied by Garg, Goulding, Harvey, and Mazzoleni has intuitive appeal. Multiple metric (or ensemble) strategies have been demonstrated to add value in many areas. For example, in their 2020 study “Is (Systematic) Value Investing Dead?” – Summary Ronen Israel, Kristoffer Laursen and Scott Richardson of AQR Capital Management showed that a diversified (equal-weighted) combination across individual value metrics (such as p/b, p/e, ev/s, ev/cf) generated a strongly positive risk-adjusted return (t-stats well above conventional levels)—demonstrating the benefits of using an ensemble approach versus one single metric. AQR also uses multiple signals in their managed futures strategies (a short-term or fast signal, an intermediate-term signal, and a long-term reversal signal). In addition, the idea that different markets behave differently is an interesting idea. Hopefully, we will see future research explore this concept in greater depth.

Editor’s note: Trend following is an interesting concept that allows investors to shape portfolio outcomes in unique ways to achieve different financial objectives. However, it is important to note that no amount of financial engineering will eliminate the difficult journey investor’s must face when utilizing trend following strategies. Hence the reason we often say, Trend Following is the epitome of no pain no gain.

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.