Empirical research, including the 2020 study “An Empirical Evaluation of Tax-Loss Harvesting Alpha” and the 2023 study “Expected Loss Harvest from Tax-Loss Harvesting with Direct Indexing,” has found that tax-loss harvesting strategies in separately managed accounts (SMAs) can improve the post-tax returns of an investment portfolio by employing a strategy of selling positions in securities with losses in order to generate capital losses that can be used to offset gains generated in the overall portfolio. While long-term losses are generally hard to realize systematically because stock positions on average appreciate over time, in the short term, volatility allows for the capture of short-term losses. The result is that most losses end up being short term. Those losses can be used to offset highly taxed short-term gains. Among the key findings of the research on tax loss harvesting are:

- The tax alpha varies strongly across different periods. For example, In a study about tax-loss harvesting alpha, during the 1926-1949 period, the average annualized alpha was 2.29% per year. Conversely, during the 1949-1972 period, the average annualized alpha was a modest 0.57% per year.

- A key benefit of tax-loss harvesting is that it can allow investors with concentrated positions in low-basis stock to diversify their holdings as tax-loss harvesting losses are realized—the losses are used to offset some, or all, of the taxes due on the sale of the low basis stock. It can also help offset the capital gains taxes generated by less tax efficient (higher turnover) equity strategies such as those of active managers.

- The performance of the tax-loss harvesting strategy can be substantially affected by the rate of investor contributions into and out of the portfolio. As capital flows into the portfolio, new shares need to be bought, generally at a higher cost basis, providing more opportunities to harvest losses.

- Because stocks are expected to increase over the long term, the volatility environment in the first few years of a tax-loss harvesting program is a critical determinant of the tax alpha.

- Tax alpha increases monotonically with the tax rate.

- Tax alpha increases with a higher contribution per month as additional cash contributions reduce the importance of starting tax-loss harvesting in a bear market for a productive loss-harvesting experience.

Direct Indexing and ETFs

The empirical research comparing the tax benefits of direct indexing versus ETFs, including the 2022 study “Optimized Tax Loss Harvesting: A Simple Algorithm and Framework,” and the 2023 study “A Tax-Loss Harvesting Horserace: Direct Indexing versus ETFs” has found that just as intuition suggests, a portfolio of stocks should provide greater opportunities for harvesting, as well as increased consistency because harvesting opportunities can be present in individual holdings even when the market has positive returns.

Taking Direct Indexing and Tax-Loss Harvesting to the Next Level

Joseph Liberman, Stanley Krasner, Nathan Sosner, and Pedro Freitas, authors of the September 2023 study “Beyond Direct Indexing: Dynamic Direct Long-Short Investing,” examined if the utilization of leverage and long-short strategies motivated by the literature on factor-based investing could improve on the tax benefits of direct indexing and tax-loss harvesting.

They began by modeling three types of tax-aware strategies. The first was a direct indexing strategy. The other two represented alternative approaches to long-short factor investing. Strategies of the first type, referred to as “relaxed-constraint,” expressed index beta using individual stocks. For example, a 150/50 strategy would hold 150% of its net asset value in long stocks and 50% of its NAV in short stocks. The second type implemented index beta by holding an index mutual fund or ETF, and used individual stocks to put on the long and short extensions. For example, a 150/50 strategy would hold 100% of its NAV in an index fund, 50% of its NAV in long stocks, and 50% of its NAV in short stocks. They called these “composite long-short.”

They then introduced these tax-aware strategies with different levels of leverage and tracking error. Their data sample and strategies were constructed over the Russell 1000 Index universe and tracked the Russell 1000 Index performance. All the strategies were rebalanced at a monthly frequency. In each rebalance, the strategy sought to defer tax gains and realize tax losses while maintaining a tracking error of 1% with respect to the benchmark index for the long-only direct indexing strategy. The tax-aware long-short factor strategies were modeled as follows.

In each monthly rebalance, relaxed constraint strategies maximized expected active pretax returns, deferred gains, and realized losses subject to tracking error and leverage constraints. They derived expected active pretax returns from an alpha model based on value, momentum, and quality investment themes, or factors, with each factor receiving an equal risk weight. They modeled three levels of leverage and tracking error: 150/50 at 2% tracking error, 200/100 at 4% tracking error, and 250/150 at 6% tracking error.

The composite long-short strategies consisted of a passive hypothetical Russell 1000 Index fund and beta-zero, long-short portfolios of individual stocks (market-neutral portfolios).

They simulated 27 10-year-long histories. The simulations began in January of each year from 1986 to 2012, with the last 10-year simulation beginning in January 2012 and ending in December 2021. After a strategy was seeded on the first day of the simulation, there were no contributions or redemptions of capital during the simulation period. For computing tax benefits, they used the top federal tax bracket rates in the year 2022 inclusive of 3.8% net investment income tax: 40.8% for short-term capital gains and ordinary income, and 23.8% for long-term capital gains and qualified dividend income. Tax benefits were computed monthly as a percentage of the month’s beginning NAV and then annualized. They assumed that capital gains were taxed according to their character (short term at 40.8% rate and long term at 23.8% rate), all capital losses (whether long-term or short-term) were used to offset only long-term capital gains, and a 10% effective tax rate was applied to incremental unrealized gains.

Here is a summary of their key findings:

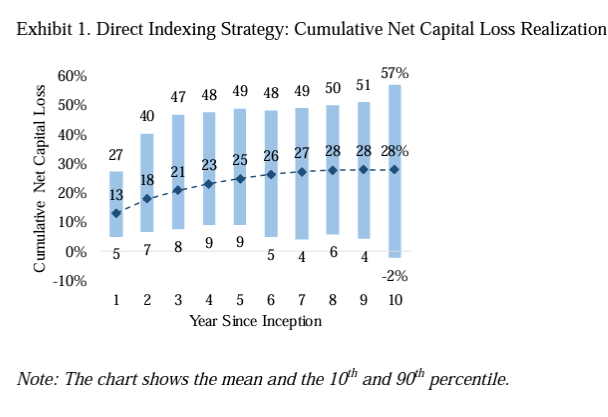

On average, net losses offered by direct indexing tapered off after the first few years since inception – the cumulative net capital loss amounted to 13% in year one, crossed a 20% mark in year three, and closer and closer towards 30% in the last five years of the 10-year simulations.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

- Due to their sensitivity to market environment variables – market return and stock-level volatility – direct indexing strategies had a very substantial dispersion of net loss outcomes, including in year one. After half a decade of investing in the direct indexing strategy, the cumulative net capital loss could be as high as approximately 50% (or more) with 10% probability or as low as approximately 5% (or less) with 10% probability.

- On average, during the entire 10-year simulation period, the gross-of-costs pretax alpha of the direct indexing strategy was approximately zero – the strategy successfully tracked the index. In years one to five, the average annual turnover of the strategy was 155% of the NAV, which led to a small negative net-of-costs pretax alpha of negative 12 basis points. However, this pretax underperformance relative to the benchmark was more than compensated by a tax benefit estimated to be 69 basis points on average, with the 10th and 90th percentiles at 40 bps and 118 basis points, respectively. As the portfolio matured, the tax benefits were reduced. The tax benefit in years six to 10 was 9 basis points on average, with the 10th and 90th percentiles at negative 2 and 27 basis points, respectively. The average annual turnover of the strategy, mostly induced by loss-realization trades, declined accordingly to 55% of the NAV.

- The ability to realize net tax losses per dollar of the NAV generally increased with leverage because position sizes, and thereby potential economic losses, became larger relative to the NAV. For example, relaxed constraint 150/50 on average realized a 100% cumulative net capital loss in about seven years. After nine years, fewer than 10% of the simulated vintages realized a capital loss less than 100%. The higher leverage strategies achieved a 100% capital loss faster. For relaxed constraint 200/100, it took less than three years on average to realize a 100% cumulative net capital loss, and after four years fewer than 10% of the vintages failed to achieve a 100% capital loss. Relaxed constraint 250/150 reached a 100% capital loss in less than two years, and only about 10% of the vintages failed to realize a 100% capital loss after two years. Composite long-short strategies produced similar results, though with wider dispersion of outcomes in the later years.

- For the leverage-tracking error combinations, reduction in tracking error reduced capital losses and tax benefits, as a tighter tracking error constraint began to limit the opportunities for deferring the realization of gains. The opposite was also true: By taking a greater economic risk, and thereby a greater exposure to the alpha model, an investor could also increase the tax benefits derived from the strategy.

- Relaxed constraint and composite long-short strategies had a high level of alpha-model-induced turnover. For those strategies, tax-aware optimization helped achieve a desired level of alpha-model exposure without sacrificing tax efficiency – for factor-based strategies, tax efficiency comes not from accelerating losses but rather from slowing down the realization of gains.

- Both relaxed constraint and composite long-short strategies significantly outperformed the direct indexing strategy from both a pretax and tax perspective, although the dispersion of outcomes was somewhat larger under composite long-short than under relaxed constraint.

The Major Source of Tax Benefits is Surprising!

Krasner and Sosner extended their analysis on the tax benefits of long-short strategies in their study “Loss Harvesting or Gain Deferral? A Surprising Source of Tax Benefits of Tax-Aware Long-Short Strategies,” published in the Summer 2024 issue of The Journal of Wealth Management. They constructed two types of 250/150 long-short strategies: tax-aware and tax-agnostic. The two strategies are identical in every respect except that the tax-agnostic strategy removed the tax term from the objective function of the long-short portfolio optimization routine, focusing exclusively on maximizing net-of-transaction-costs alpha, subject to volatility, leverage, and beta-zero constraints. Portfolios were rebalanced monthly, adjusting the weights of the index fund and the long-short stock portfolio to maintain a beta-one index exposure as well as the target leverage and tracking error of the overall strategy. Expected pre-tax returns were derived from an alpha model based on value, momentum, and quality investment themes, or factors, with each factor receiving an equal risk weight. Their data sample covered the 34 rolling three-year periods from 1986 through 2021.

Following is a summary of their key findings:

- The high magnitude of net losses for tax-aware, long-short factor strategies is achieved by deferring the realization of taxable gains while continuing to realize tax losses as a part of the natural strategy portfolio turnover—there was not much difference between the tax-agnostic and tax-aware strategies in terms of long-term losses.

- Much like tax-agnostic factor strategies, tax-aware factor strategies mostly trade in accordance with the alpha model, explaining the ability of tax-aware long-short factor strategies to outperform their benchmarks before tax.

- Tax-aware long-short factor strategies primarily rely on liquidating loss positions and creating new positions when following the recommendations of factor-based alpha models—explaining their ability to outperform benchmarks before tax.

Krasner and Sosner noted:

“By investing in the tax-aware instead of the tax-agnostic strategy, over a three-year period, an investor gives up about 12% in pre-tax return and, in return, achieves an approximately 125% greater cumulative net loss. If this net loss is fully utilized to offset long-term gains taxed at a 23.8% rate, its value to the investor is 30%, which is more than two times greater than the reduction in pre-tax return.”

Investor Takeaways

With the decimalization of prices, reduction in commissions/fees from broker-dealers and custodians, and the competition from high-frequency traders, trading costs have fallen sharply, reducing the hurdles to effective tax management. In addition, financial technology has greatly improved, and custodians are required to track cost basis, making reporting much easier. As tax-aware investing, including tax-aware long-short investing, has become more cost-effective, it has become more important for investors.

Among the key takeaways is that even direct indexing strategies need to deviate from benchmark weights to achieve their loss-harvesting benefits, carrying the risk of underperformance relative to the benchmark. In addition, direct indexing strategies will have higher transaction costs, which result from the loss-harvesting trades, and possibly higher management fees due to added complexity. Leverage and shorting can further increase risks and costs of tax-aware strategies. And the tracking error of strategies that utilize leverage and shorting will likely be higher than that of direct indexing, leading to a higher risk of underperforming the benchmark. With that said, these strategies will likely have greater opportunities to realize capital losses than direct indexing. In addition, higher leverage leads to financing costs, and the higher complexity of managing long-short strategies will likely result in higher management fees.

A third takeaway is that tax-aware, long-short factor strategies allow investors to enjoy not only substantial tax benefits but also a diversifying pretax alpha derived from factor investing. With that said, the results demonstrated that the speed with which 100% cumulative net capital loss is achieved by relaxed constraint and composite long-short strategies depends on the level of leverage and tracking error an investor is prepared to tolerate. Said differently, economic risk and tax benefits are correlated.

Larry Swedroe is the author or co-author of 18 books on investing, including his latest, Enrich Your Future: The Keys to Successful Investing.

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.