Is Tiger Woods Loss Averse? Persistent Bias in the Face of Experience, Competition, and High Stakes

- Pope and Schweitzer

- A version of the paper can be found here.

- Want a summary of academic papers with alpha? Check out our Academic Research Recap Category!

Abstract:

Although experimental studies have documented systematic decision errors, many leading scholars believe that experience, competition, and large stakes will reliably extinguish biases. We test for the presence of a fundamental bias, loss aversion, in a high-stakes context: professional golfers’ performance on the PGA Tour. Golf provides a natural setting to test for loss aversion because golfers are rewarded for the total number of strokes they take during a tournament, yet each individual hole has a salient reference point, par. We analyze over 2.5 million putts using precise laser measurements and find evidence that even the best golfers—including Tiger Woods—show evidence of loss aversion.

Alpha Highlight:

Scoring in golf is fairly simple, you add up the number of shots it takes you to get the ball in the hole. That being said, golfing–like investing–is simple, but not easy:

If the goal is to get the lowest score possible, where every shot counts the same, then every shot is important. In a perfectly efficient market, one would expect that PGA tour players would exhibit the same focus and effort on every shot. Turns out they don’t!

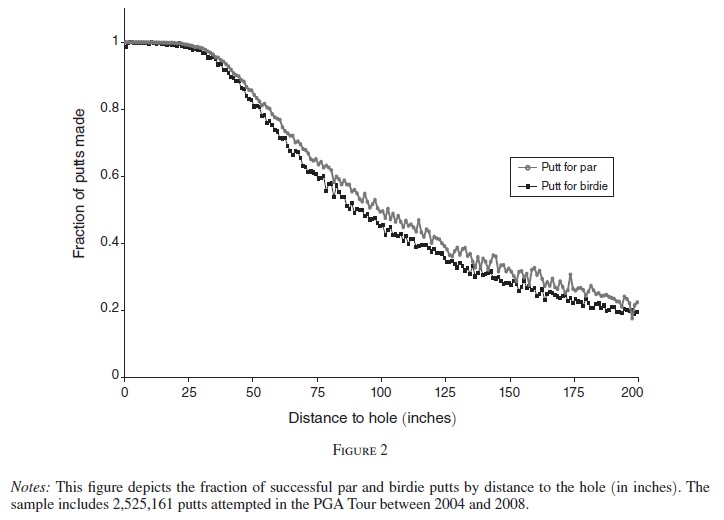

This study examines over 2,500,000 putts on the PGA tour from 2004 to 2009. The finding should be a warning beacon for anyone who still believes that behavioral bias can’t influence important outcomes: given a similar putt, PGA tour professionals perform better if the putt is for par as opposed to a birdie (i.e., loss aversion).

What is the theory behind this “loss aversion” among professional golfers?

This paper describes it very well:

Rather than make consistent decisions over final wealth states, Kahneman and Tversky (1979) postulate that economic agents evaluate decisions in isolation with respect to a salient reference point. In Prospect Theory, Kahneman and Tversky (1979) propose a reference-dependent theory of choice in which economic agents value gains differently than they value losses in two key ways. First, economic agents value losses more than they value commensurate gains (loss aversion); the “value function” is kinked at the reference point with a steeper gradient for losses than for gains. Second, economic agents are risk seeking in losses and risk averse in gains (risk shift); the utility function is convex in the loss domain and concave in the gain domain.

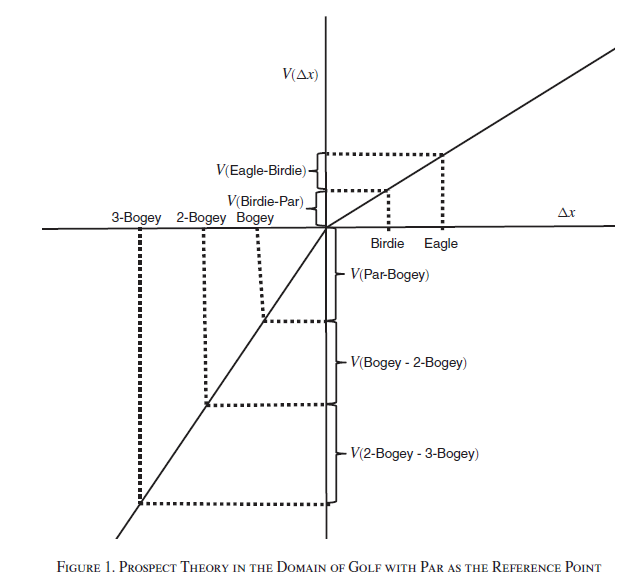

Here is a picture describing this theory for golf:

The picture above shows that “gains” such as a birdies (relative to par) have less utility (value) than the corresponding “loss” such as bogeys (relative to par). Essentially, “losses” hurt more than “gains.”

So how could this affect a golfer?

Let’s say I have a 5 foot putt.

- Scenario 1: If this putt is for “birdie” I may focus less than if this putt is for “par.” Why? Because the utility, or value derived, from making the birdie putt is relatively small.

- Scenario 2: This putt is for “par”. I will be more focused in this situation, because the fear of hitting a bogey is so painful.

The rational solution suggests that every put should get equal attention–they all matter. However, according to loss aversion theory, golfers will be more focused on their par puts than their birdie puts, all else equal.

But how does this affect PGA tour professionals, who should know that every putt counts the same, and who are playing for millions of dollars?

Here is the evidence:

The evidence is stunning, but is perfectly described by prospect theory: given a similar putt for birdie or par, PGA tour professionals make more par putts!

Robustness:

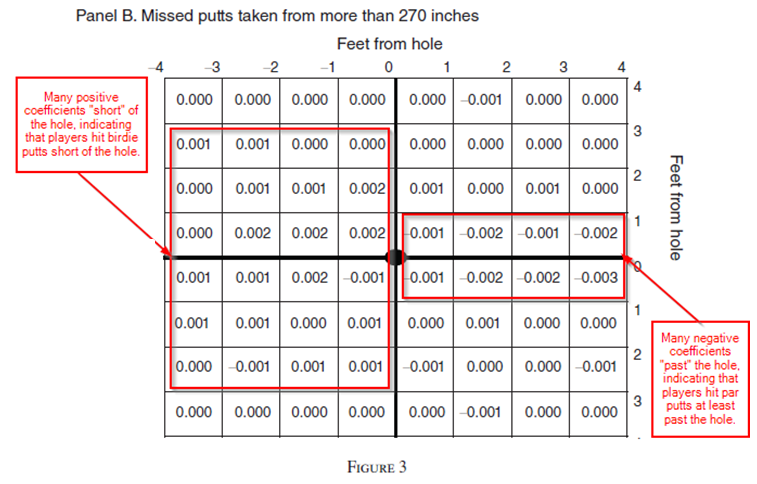

Another prediction is that golfers will be more risk averse when putting for birdie relative to par. This could be tested by examining how hard one hits the ball. It is a fact that you need to at least hit the ball to the hole to make the putt. However, many golfers (including myself) tend to lag the ball up to the hole, leaving the putt short, as the fear of hitting the ball “too far” past the hole makes players lag the putt short of the hole. If golfers are more risk averse for birdie putts, we may expect to find that birdie putts tend to come up short of the hole. The paper examines this idea.

Here is the evidence:

In the above picture, a positive (negative) regression coefficient indicates that birdie putts are more (less) likely to come to rest in the box than par putts. Examining the picture, we find many positive coefficients short of the hole, and many negative coefficient pas the hole. This indicates that PGA tour professionals tend to leave birdie putts short compared to par putts. This is again stunning, as leaving the ball short of the hole gives you “zero” probability of making the putt (I will try to remember this next time I go golfing).

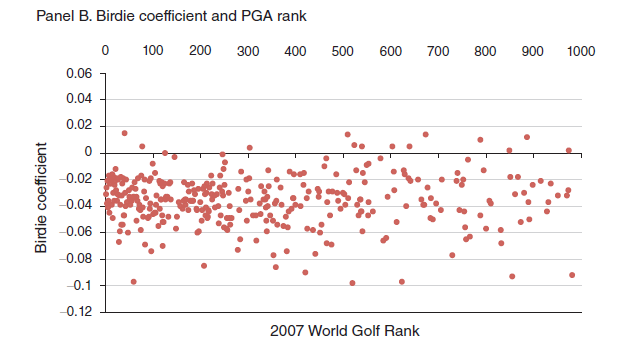

What about the skill of the golfer? From 1998 – 2008, Tiger Woods was the best player in the world.

Did this loss aversion affect Tiger?

Here is a plot of the player’s world ranking and their corresponding relative accuracy of birdie putts relative to par putts (a negative number means that the golfer is less accurate for birdie putts relative to par putts):

The above chart shows that most PGA golfers (including Tiger) exhibit this loss aversion, and are less accurate on birdie putts relative to par putts (as shown with the negative coefficients). In theory, competition and incentives should make the PGA tour market more efficient, yet this paper documents that PGA tour professionals exhibit loss aversion bias.

How much did this cost these golfers?

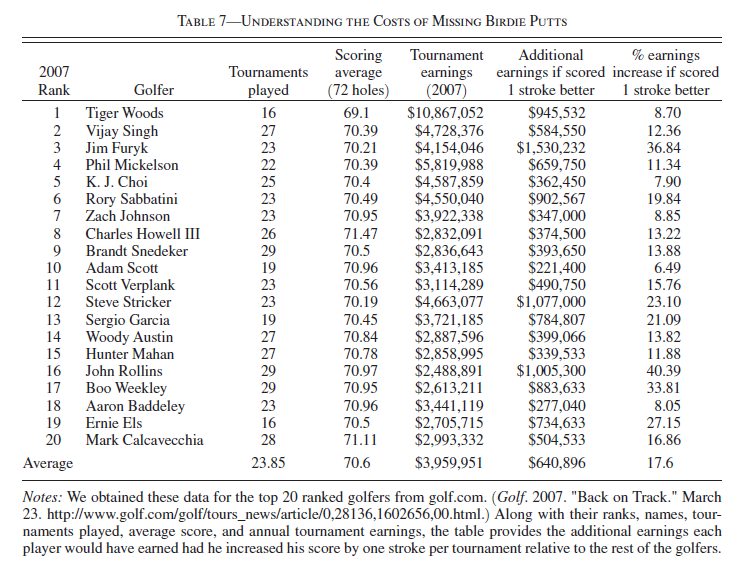

The paper estimates this here:

From this table, it appears that PGA players left hundreds of thousands of dollars on the table, due to their own loss aversion.

Besides potentially helping our own golf games, by reminding us to be less risk averse on birdie putts, can this be extended to other fields?

At Alpha Architect we believe that behavioral biases can affect stock prices, and try to build models to exploit investor bias. The trick while simultaneously trying to contain our own bias.

Let us know what you think, can this be extended to stock markets?

About the Author: Jack Vogel, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.