“Competition is a sin.”

–Attributed to John D. Rockefeller

Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

We get the following question all the time:

I went to buy your strategy/MF/ETF at Big Bank’s broker [UBS, MS, GS, Merrill, Wells Fargo, etc.] and they said your ticker is blocked because of “due diligence.” What’s up?

Answer: We haven’t engaged in their pay-to-play scheme yet.

This post gives an inside look at how fund distribution platforms work: Their economics, their incentives, and how they operate.

One of the greatest monopoly stories in US history is the American railroad. During the 19th and 20th centuries, railroad barons quickly established a distribution network that revolutionized transportation. The railroad operators monopolized the transport of goods and services, passing along high rents to the American consumer, reaping enormous profits along the way.

Today’s railroad monopoly is the banking system. Leveraging their distribution networks to sell proprietary financial services, banks reap tremendous profits, usually at the expense of their clients. In a competitive market, poor client outcomes would force banks to change their behavior. And at the margin, firms such as Vanguard, Interactive Brokers, and a flood of fee-only independent advisors, have chipped away at the banks’ “railroad.” However, banks, and their powerful distribution capabilities, have managed to limit the competition’s advance. They continue to push high-fee, tax-inefficient, opaque, non-client-friendly products into the financial services marketplace. Competition is certainly changing the market for the better, but there is an overwhelming majority of investors that remain unaware of a bank’s conflict of interests and its expensive consequences.

We believe transparency and illumination of bank economics will help consumers make better decisions. In this essay, we dive into the economics of bank distribution and why their “railroad” often leads to poor client outcomes. Our hope: readers become more informed, more confident, and most importantly, stand up to their financial service providers and ask them the tough questions. Specifically: force them to detail how–and why–they get paid.

The bank railroad and open architecture

As recently as a few years ago, most banks were “closed architecture,” meaning they only offered their own investment products to clients. Instead of wearing different hats, financial advisors and product salesman were the same person. While the client wanted to maximize after-tax, after-fee, risk-adjusted returns, the advisor/broker wanted to maximize his personal profits. Not surprisingly, year-end bonuses trumped client needs, and billions of dollars in expensive, tax-inefficient products burrowed their way into client portfolios.

Naturally, clients got upset. Imagine John Q. Investor, having saved for decades, finally retiring and purchasing his dream sailboat. Pulling into port to christen the SS Frugal, he looks astern to see his financial advisor steering a new, luxury yacht. And that was the scenario that played out between banks and their clients for years. The customer got dinghies; Advisors got yachts.

Angry clients began to push back. Fearing mass defections, banks and their associated advisors/brokers (“brokers”), capitulated and expanded their product offering to include non-proprietary products. Now the playing field was level and every product was available to clients. The golden era of “Open Architecture” was upon us and the client/bank relationship entered a new era of peace and prosperity, right? Not so fast.

Here is a Barron’s article from a few years ago discussing the open architecture concept:

…the big wealth-management outfits have reluctantly been building out “open architecture” platforms, the trade term for offering a wide range of investment products run by outside managers.

Reluctantly building open architecture?

Why would banks hate more variety, cheaper solutions, and better returns? Aren’t these things good for the client? Doesn’t this allow their clients to get yachts too?

Open architecture allows third parties on a bank’s distribution railroad. Plainly stated, open architecture increases competition and customer choice. We’ve seen this movie before: Uber and taxicabs, Tesla and car dealers, e-publishing, and bookstores. Bypassing the middleman is often a good thing for the consumer, but it also means the middleman makes less money.

And if there is one thing middlemen hate, it’s making less money!

So…let’s travel on the bank’s railroad and understand why banks make less with open architecture, and more importantly, why banks are fighting tooth and nail to limit open architecture altogether.

All aboard the BS Express, destination: your retirement account.

Banks make billions by selling their own asset management products. They sell directly to clients (e.g., individuals with a retirement account) and via advisors/brokers in their network (e.g. local investment advisor backed by a big bank brand). Bank’s clients/advisors are only allowed to buy “approved” products. Of course, the bank owns the “approval” process and determines what is allowed to get on their platform and what is kicked to the curb.

Of course, some filtering should be done to prevent fraudulent products and outright scams. One only needs to watch three minutes of Wolf of Wall Street to see why quality control is necessary (sidenote: do NOT watch Wolf of Wall Street with your parents…very awkward).

However, there is a clear opportunity for banks to manage their approval process and skew approvals toward products that reward the bank. Does the product generate lots of fees? If yes, chances are the product will be approved before a low-fee, external alternative. If customers demand a low-fee external product, why not slap an “access fee” on the top to recoup the revenue? If you need an example of this practice, kindly Google “Kickback scheme” or chat with your local Washington DC lobbyist.

But what about the client??? These “approved” products may not be the best option. In fact, such products are almost never the best option because of–drumroll please–higher expenses. Herein lies the conflict of interest: banks want to maximize profits, but clients want to maximize after-cost risk-adjusted performance.

Here is a quick example. Consider a client that walks into “MegaBank” looking to invest for retirement. The client asks the MegaBank advisor about their options:

- Buy MegaBank’s US Large Cap Equity Mutual Fund at a 1.5% management fee.

- Buy a sponsored product, which has a hidden 0.50% kickback fee to MegaBank.

- Buy a 0.05% Index Fund and the bank makes a $10 commission.

From Megabank’s perspective, option 1 can pay thousands of dollars, option 2 can pay thousands of dollars, and option 3 will barely pay for the rep’s double mocha soy latte after the client meeting.

What option do you think Megabank “advisor” will recommend?

How are big banks dealing with the open architecture dilemma?

The Banks’ dilemma is getting worse. The conflict of interest mentioned above has been highlighted in the mainstream media, and key outlets smell blood in the water. For example, JP Morgan has been embroiled in some controversy over this issue over the last few years, as detailed here and here.

Some banks have sought to address this conflict of interest head-on and alter their fee structures. Other banks have sold off their mutual fund complexes entirely. Consider Barclays–A recent Barron’s article has a quote from Barclays, which, according to the article, has eliminated internal products and embraced open architecture:

“We are completely on the same side of the table as the client because we don’t have to support an internal asset-management business,” says David Romhilt, head of manager selection at Barclays.

Wow!

Did Barclay’s really just sell off a tremendously profitable business division to “be on the same side of the table” as their clients? Should we believe that a large bank would willingly open up the railroad tracks so that others may travel freely?

Of course not.

Let’s dig a little deeper into Barclay’s clever move and the hidden economics of distribution.

Makin’ it Rain in an Open Architecture World

Any economics student can tell you that owning the railroad is what makes money, not the railcars. The same lesson applies to our Barclay’s example – selling their own product doesn’t matter because they own the tracks! And the beauty of owning the rail tracks is you get to charge other railcar operators a fee for riding on your network. Eureka!

Banks are skilled at charging fees to railcar owners (i.e., outside investment managers) that want to ride on their tracks. But the payment isn’t always direct–that would be too transparent and clients might get mad. Years ago, one way that banks and their brokers derived profits from external products was via “directed brokerage.” Under directed brokerage, a bank/broker would enter into a fee-for-service arrangement with a mutual fund. The bank would promote the fund to their clients, and in return, the fund would channel trading/execution orders to the bank. Bank/brokers get extra commission revenue and the fund managers get access to customers. The only loser in this arrangement is the client, who gets stuck with extra fees (and oftentimes, they aren’t even aware of them).

Thankfully, the SEC made this practice illegal in 2004, but the ink wasn’t even dry on the rules before alternative kickback schemes arose. Here is a WSJ article discussing the ban:

Still, the crackdown on what is known as “directed brokerage” isn’t likely to alter the underlying environment in which hundreds of fund companies, all competing for “shelf space” at the brokerage firms favored by individual investors, feel obliged to pay for that access in one way or another. “If they can’t pay through directed brokerage, then they will pay another way,” predicts Cynthia Mayer, a fund-industry analyst at Merrill Lynch.

Shelf space. Railroad access. It’s all the same. Funds pay, banks get a fee, and the client funds the journey…but it gets worse.

The WSJ article above goes on to discuss the rise of “revenue sharing,” which is the model that prevails today. Under a revenue-sharing arrangement, instead of directing trades to the bank, the fund agrees to share a portion of its management fees with the bank. The bank maintains profits by awarding scarce “shelf space,” and the fund gets distribution on the bank platform. Generate a lot of fees for the bank? Earn more shelf space! Don’t worry, you may knock some cartons of good product off the shelves, but that’s ok because the bank is getting paid!

Revenue Sharing Junction: What’s your function?

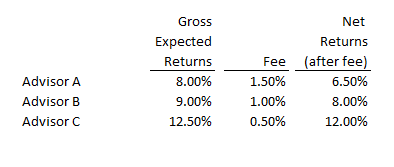

Let’s say you’re a financial advisor/broker associated with Megabank. You want to recommend a product to your client and you are choosing between 3 advisor strategies, with the following characteristics (assume similar risk across all three options).

Note that Advisor C is clearly best for the client: higher gross expected returns and lower fees!

Now let’s look at things from the bank’s perspective.

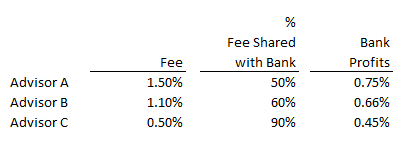

The bank has gone out and negotiated a revenue share with each of the 3 Advisors, as follows:

From the bank’s perspective, advisor A is clearly the best: the higher fee products maximize the bank’s profits, even with the lowest profit-sharing percentage. High fees rule the day: A bad deal for clients, but hey, on Wall Street, “two-out-of-three ain’t bad.”

Note that Advisor C has offered the bank a full 90% of its fee, and it still cannot compete for the bank’s favor. There is simply no way for Advisor C to match the bank’s profitability derived from the inferior advisors.

So what will the railroad track owner (i.e. bank), do?

The easy answer is to block the Advisor C railcar from getting on the tracks. But there is a problem: the client has heard about open architecture and wants the cheaper, tax-efficient railcar. How can the bank quietly prevent customers from demanding product C? Why not place product A on a preferred list of securities with more research and snazzier reports? Or maybe make the client sign a really scary waiver in order to purchase product C? Better yet, make everything manual and require paper copies to slow things down. Perhaps we create an “approval” process that fastracks profitable products and buries the least profitable products in an administrative black hole with no chance of escape?

Think these are made up examples? Independent, affordable, and client-friendly investment products hit the bank brick wall every time they enter a bank boardroom. Bankers aren’t stupid–they own all the yachts for a reason! And the last thing a banker will do is invite competition in via the front door, without a quid pro quo that ensures they can somehow make money off their clients.

A personal story underlines this reality. Consider our own firm, Alpha Architect. We happen to be an independent value-investing focused asset manager with a handful of tax-efficient active products. The banks have all invited us to have a chat because we’ve raised over $200mm in short-order, and we’ve got the type of pedigrees that sell on Wall Street. So we took a stroll up to New York City to hang out with the “Masters of the Universe.”

We met with one of the largest banks on the planet–that shall remain nameless–and we had a conversation with one of their top private bankers. Frankly speaking, a good guy – super friendly, successful, smart, and so forth. A perfect relationship guy to manage client needs. We discussed various products we offered that had compelling value propositions. The private banker loved our pitch, and responded as follows: “Yeah, that’s certainly a unique and high-quality product, and I’m sure we could do some kind of revenue share with your stuff, but honestly, I can’t see how my guys can get paid selling it. You don’t have enough juice in your fees.”

Not enough juice in our fees?

We felt like we were trapped in a Michael Lewis novel, but it made perfect sense. As the example above highlights, lower fee products do not produce enough income for a bank. From the bank’s perspective, the quality of a product is secondary to its profitability.

So let’s summarize the new, “cleaner” open architecture model that involves divesting the bank’s in-house investment management unit:

- Deny shelf space to lower margin products. Check.

- Limit client options to high fee products. Check.

- Generate lots of bank profit. Check.

- Keep the peace with clients and branded advisors by promising “robust due diligence” on client-demanded products. Be sure to maintain steps 1-3. Check.

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the bank distribution game, the railroad monopoly for the 21st century.

But what happens when clients start asking questions?

Clients aren’t stupid and are getting smarter every day. Most realize that fees and performance matter. With the advent of technology, this reality-based battleship is picking up steam and headed full steam towards our advisors yachts (ever hear of a tiny firm called Vanguard?). Many clients are leaving big banks. For those that haven’t left (yet), let’s explore the bank’s reaction to some of their probing questions.

Specifically, what happens when a client calls their financial advisor at Megabank and says things like, “Hey, I’ve been reading about Advisor C. They seem cheaper and better than Advisor A and B. Can you let me invest in Advisor C’s products?”

What is the bank to do? A blog reader (who asked to remain anonymous, but gave us permission to reprint their remarks) faced this situation in a real-life scenario and shared his experience:

I have been interested in [ABC ETF], and actually went to try and purchase shares through my broker [XYZ Broker] last week.

Unfortunately, they had [ABC ETF] “blocked” and I could not buy it! I called customer service and apparently they have them blocked because they are awaiting receipt of some paperwork that has to do with “quality control.” I can understand that from their viewpoint they are trying to protect investors from some of the shoddy ETF products that are coming out from [various] companies, but in this instance it is working to block investors from a quality product!

This blog reader also asked us the following:

What it would take to get [ABC ETF] listed and available for trading within [XYZ Broker]?”

By now, after dissecting the economics of bank distribution, the answer should be clear: ABC ETF WILL NEVER GET ON THE PLATFORM.

And What if Asset Managers Get Smart?

Conflicted bank/broker incentives are not limited to eliminating lower-cost products from the bank’s platform. Consider a story we heard about a large mutual fund complex that was listed on a bank platform for many years, paying enormous “railcar” fees to the track owner. Over time, the funds did well, giving the mutual fund complex increased bargaining power versus the bank, which got a lower and lower percentage of the funds’ fees. Eventually, the funds demanded so much of their own fee, thus eroding so much of the bank’s profit, that the banks concluded they didn’t want to offer products from the platform anymore (i.e., they couldn’t get paid), and the funds were kicked off the platform. There were more expensive, more profitable funds the bank could put on the tracks. The high-performance railcar was causing them too many problems.

Remarkable you might say? Well, after dissecting the economics of bank distribution, this is a no-brainer. Boot the low-profit railcars from the track and finder a high-profit railcar!

But Aren’t the Banks Being Short-Sighted?

A general equilibrium economist might question the bank’s rational decision-making process. Monopolies don’t last forever. On one hand, maximizing profits via the exploitation of distribution economics is rational in the short run. However, the banks must consider the fact they operate in a dynamic marketplace. Enlightened clients and independent asset managers are finding ways to avoid the bank distribution channel (e.g., ditch railroads and fly on airplanes). And if no clients are in the bank distribution channel, the distribution channel is worthless–there are no clients to exploit!

An economist may look at the bank’s reluctance to adapt to the current, more competitive environment, as “short-sighted,” but status-quo bias, bureaucracy, regulation, and “head-in-the-sand syndrome” affect even the best institutions. Nonetheless, the long-run game is clear: the bank railroad is under attack from multiple angles, and pitchfork-bearing investors won’t be satisfied until full transparency reigns (see Indexing 2.0). Technology, client education, the rise of independent investment advisors, and direct-to-consumer marketing efforts on behalf of asset managers are eliminating the need for a middleman. The bank’s railroad is slowly becoming a relic of the past and yachts are starting to sink.

Wrapping Up Our Course on Wall Street conflict of interests

While this entire essay may sound “anti-bank,” one has to consider that it is always easy to throw grenades into the other guy’s backyard. Being a banker is tough and it is easy to hate on Wall Street banks and their conflicting incentives. But conflicted incentives are part of middleman economics–car dealers, book publishers, pharmaceuticals, grocery stores, big-box retailers, and so forth. Middlemen, while inefficient in a perfect world, can provide an economic value as an intermediary. In the bank’s defense, someone needs to match buyers and sellers in the market; someone needs to coordinate savers and entrepreneurs; someone needs to facilitate commerce! And the bank’s middleman responsibilities are tough to accomplish relative to middlemen in other industries: regulation is insane; government intervention and tampering are at all-time levels; economic incentives are often warped and people need to get food on their table. Being a banker is tough.

Nonetheless, while it is important to understand the plight of the middleman, it is also important to look out for your own best interests as an investor. And as our essay has hopefully highlighted, if you are a client working with a large bank–either directly via a private client group, or indirectly via an affiliated financial advisor–you simply won’t have access to some of the best products. You will get selective access, because the bank’s shelf space is intentionally limited, and the screening criteria will likely be based on bank profitability, not suitability for your portfolio.

Perhaps we are insane (possible) and/or jealous because the banks on Wall Street haven’t come clamoring to raise billions of dollars for our asset management products. We’d love for that to happen, but understand that nobody works for free and shelf space is a scarce resource. We have our own biases. We don’t operate as a non-profit enterprise. And yes, it is true, by educating our readers on distribution economics we are talking our own book to some extent. Nevertheless, we believe in direct-to-consumer marketing and that is part of our sales pitch. No middle man. No middle man fees.

Share this commentary with your bank-affiliated friends. Get their thoughts. Make them shoot holes in our analysis and report back to us. We’ll integrate their rebuttals and ensure we present a more even-handed story if there is one to be told. And when you share this with your advisor/broker/banker, they might tell you that platform access is limited to “protect the client.” As the story goes, the bank needs to limit shelf space because there are many shady operators and clients simply can’t understand the complexity of the marketplace. Remember, they are just trying to protect you–bankers are your guardian angel in financial markets. And while our association of bankers and guardian angels is tongue in cheek, there is certainly some truth to the claim that not everyone operating in the financial services industry is Mother Teresa.

But then ask them what the average fee is for products approved on their platform? Ask them what the revenue-sharing agreement is with the approved providers? See what they say. They may not know. We’ve seen many cases where the foot soldiers of the bank are left in the dark–how and why certain products make it on the bank’s platform is simply “performed by the smart guys in New York.”

The simple matter is that most clients know how to buy groceries, but few know how to purchase financial products. In the murky world of financial services, clients may be buying products for the first time. More importantly, this purchase is the driver of their long-term financial security. Years of hard work, thrift, and responsible life choices, are baked into each and every retirement portfolio that a banker must now serve. In short, the stakes are too high and the cards are stacked too favorably towards one party. Fiduciary responsibility matters in financial services more than in any other product category outside of urgent medical care. Shouldn’t this fiduciary have your best interests at heart? Just as you don’t want your doctor to receive kickbacks from Pfizer for overdosing you on Oxycodone, why would you want your financial advisor–or their institution–to receive kickbacks for overdosing you on inefficient, overpriced, investment product that probably won’t help you achieve your investment goals?

Moral of the story: Ask your banker, or bank-affiliated advisor these questions. If you get answers that sound like the ones above, it might be time to buy a car or an airline ticket, because traveling via railroad is a thing of the past.

This is a coauthored article by Patrick Cleary, David P. Foulke, Wesley R. Gray, PhD.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.