Serving in the Marine Corps was an unforgettable experience. Civilians often tell us “thank you for your service”; however, the real “thanks” is due to the Corps for giving us valuable life lessons. The not-so subtle teachings bestowed upon us by heavily muscled, insanely aggressive Marine Corps Drill Sergeants are still, literally, ringing in our ears: “Listen here, pond scum, you better run faster, shoot straighter, and decide quicker if you are going to win in battle!” Years later, we would test that theory in real-time, battling insurgents in Iraq.

As we trade in our flak jackets for laptops and neckties, the lessons learned in combat and are not only relevant, but vital on the battlefield of high finance. Four core lessons apply to frontlines and finance:

- Humans Are Emotional: Systematic processes beat behavioral bias.

- Rambo isn’t Realistic: Act based on evidence, not on stories.

- Complacency Kills: Focus on fundamentals and never stop learning.

- Integrity is Everything: Do things right and do the right thing.

The first three lessons all revolve around the theme of preventing overconfidence. Human beings are fundamentally prone to decision-making errors. In terms of finance, these biases can potentially create inefficient prices in the marketplace. So, lessons learned in the heat of combat also apply in the heat of fast-moving markets. We, as humans, are flawed, but we can overcome our deficiencies through systematic decision-making processes.

Underpinning all of these traits is integrity: do things right and do the right thing. Period. In the end, whether we are operating in a business environment or a military environment, integrity is everything.

Thankfully, the lessons learned in the military kept us alive and brought us home. Today, we continually discover that the “combat classroom” proves to be the best preparation for a deployment to Wall Street.

Note: A formal published version of this article was published via IMCA’s Investments and Wealth Monitor

A PDF version of this is available here.

Introduction:

We first met in 2001 as undergraduates at Wharton. In many ways, we were totally different: Wes was a 5’10,” 160lb pole-vaulting quant-geek; Patrick was a towering 6’4,” 225lbs rugby player and fraternity president. Despite our differences, we had one thing in common–we both wanted to be Marines. In the context of an elite Ivy League university, finding other individuals with a desire to join the service was nearly impossible. We were friends, immediately. Wes being a few years older than Pat, he was the first one on the chopping block to sign up for the Corps.

Wes wussed out.

As luck would have it, another opportunity fell in his lap–a full-ride scholarship and stipend to attend the University of Chicago finance Ph.D. program. With a heavy heart, Wes decided against the Marines and entered the Ph.D. program.

Fast forward a few years.

Pat was set up to graduate from Wharton and go directly into the Marines. He had completed boot camp and was feeding Wes detailed stories of misery and pain. Meanwhile, Wes was suffering his own pain in the form of differential equations and esoteric statistical theories. But Pat’s boot camp updates only reinforced his desire to follow suit. Wes formulated a plan and set up a meeting with his Ph.D. coordinator. The Ph.D. program and the advisors were a bit perplexed by his desire to serve in the Marines, especially since the Iraq War was in full swing, but they were supportive. Assuming he could pass the composite exams, he would be granted four years of “special leave.” He passed his exams, signed his life away, and joined the Marines. Wes’ “special leave” had just begun.

We both ended up serving for four years, from 2004 to 2008. Pat specialized in combat engineering and Wes served as a ground intelligence officer. Both of us deployed to Iraq and learned a great deal about leadership, humility, and being part of a team.

When Wes’ contract expired, he went back to Chicago to finish his Ph.D. dissertation and eventually landed an academic post at Drexel University, based in Philadelphia–his wife’s hometown. He also founded an asset management firm, Alpha Architect. Meanwhile, Pat left the Corps and entered an MBA program at Harvard. He eventually ended up at the Boston Consulting Group as a management consultant, also based in Philadelphia–his wife’s hometown (see a pattern yet?). Five years later, and with a lot of arm-twisting, Wes finally convinced Pat to join the Alpha Architect team as its Chief Operating Officer. A nine-man team now manages an emerging asset management firm dedicated to empowering investors through education. We have over $250mm in assets under management1 and seek to deliver high-conviction, tax-efficient strategies at affordable costs. The lessons we learned in the military guide all of our business and investment decisions. The four biggest lessons learned are as follows:

- Humans Are Emotional: Losing money is an emotional event; getting shot at is even more emotional. A systematic approach for handling chaotic environments is critical to success.

- Rambo isn’t Realistic: Pumping iron and strapping hundreds of rounds across our chest might work in the movies, but in real-life, evidence-based approaches to warfare are much more effective.

- Complacency Kills: Success is often the surest way to predict defeat. Victory leads to overconfidence, overconfidence leads to laziness, and laziness can lead to death.

- Integrity is Everything: If you can’t trust the man to your left and your right, you cannot accomplish the mission. Honest communication and full transparency are paramount to any endeavor.

LESSON 1: Humans Are Emotional– Systems Beat Behavioral Bias

While stationed in Iraq, we saw stunning displays of poor decision-making. Obviously, in areas where violence could break out at any moment, it was of paramount importance to stay focused on standard operating procedures. But in extreme conditions where temperatures regularly reached over 125 degrees, stressed and sleep-deprived humans can sometimes do irrational things.

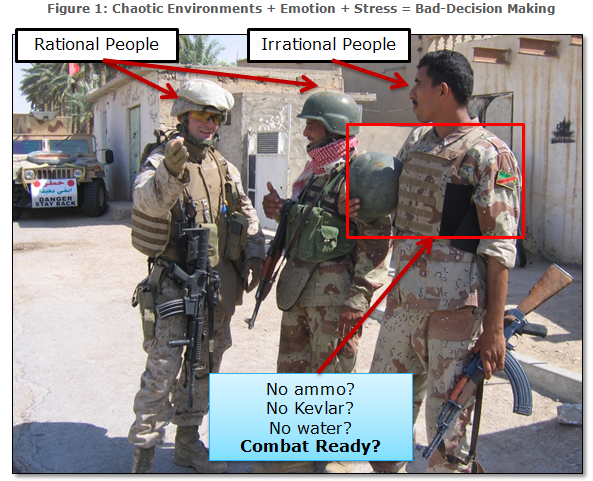

For example, carrying 80 pounds of gear in the frying desert sun makes you hot. But many things that are necessary for survival in a combat environment, such as extra water, ammunition, and protective gear, are heavy. A completely rational thinker weighs the cost of carrying gear (sweating profusely, uncomfortable, and so forth) against the benefits (not dying). A more emotionally-driven decision-maker disregards a cost/benefit analysis and goes with his natural instinct–toss all the gear, get some fresh air, and hope for the best. An example of a rational approach to combat and an irrational approach to combat are highlighted in Figure 1.

In Figure 1, Wes is situated at a combat checkpoint in Haditha, a village in Al Anbar Province. He is explaining to his Iraqi counterparts how to set up a tactical checkpoint. A quick inspection of the photograph highlights how a stressful environment can make some people do irrational things. Wes and his Iraqi friend in the photo are wearing Kevlar helmets, carrying extra ammunition, and have a water source on our gear.

- The Kevlar is important because mortar rounds are inbound.

- Rational reaction: wear your kevlar!

- The ammunition is important because one needs ammunition in a gunfight when terrorists are slinging hundreds of 7.62mm rounds in one’s direction.

- Rational reaction: carry ammo!

- Finally, water is important, because in 125 degree weather a lack of hydration can lead to heat stroke.

- Rational reaction: carry water!

And while all of these things sound rational, the Iraqi on the right isn’t wearing a Kevlar, isn’t carrying extra ammo, and doesn’t have a source of water.

Is Wes’ irrational Iraqi friend abnormal? Not really. All human beings suffer from behavioral bias and these biases are magnified in stressful situations. After all, we’re only human.

The conditions we describe in Iraq are analogous to conditions investors find in the markets. Watching our hard-earned wealth fluctuate in value is stressful. Stressful situations breed bad decisions. To avoid the potential for bad decisions in stressful environments, we need to deploy systematic decision-making.

The Marine Corps solution bad-decision making involves a plethora of checklists and standard operating procedures. To ensure these processes are followed, the Corps is religious about repetitive training. The Marines want to “de-program” our gut-instincts and re-program each Marine to “follow the model.” And while this might sound a bit Orwellian, automated reactions in chaos give us the best chance of survival. In combat, something as simple as a dead battery in a radio or a forgotten map can be the difference between life and death. To make good decisions in stressful situations, Marines follow a rigorous model that has been systematically developed and combat proven. The lesson is clear: in order for decision-making to be effective, it must be systematic.

LESSON 2: Rambo Isn’t Realistic — Act Based on Evidence, Not on Stories

For many civilians, their only “experience” of war is from video games and Hollywood movies. A classic example is the Rambo movies series. Rambo is a 1980s action movie series starring Sylvester Stallone as a deranged Vietnam War Special Forces veteran hell-bent on blowing things up and killing anyone who gets in his way. Rambo has a remarkable ability to kill waves of foreign soldiers furiously shooting in any direction. For example, in Rambo III, Rambo kills 132 enemies and is involved in 38 episodes where he manages to avoid getting killed by enemy gunfire.2

| Combat Statistics for John Rambo (Rambo III) | Result |

| Total number of people killed by Rambo | 132 |

| Number of people killed per minute | 1.30 |

| Sequences in which Rambo is shot at without significant result | 38 |

Unfortunately, Rambo’s combat experience is not realistic (we know, surprising). Rambo is a story and Rambo’s actions are not based on evidence. And yet, everyone wants to believe there is a heavily muscled superstar warrior who is invincible. We see this same element of “hero worship” in financial markets. Investors want to believe equally unbelievable stories — for example, that certain managers have magical powers to beat the market every year for eternity. But why do we believe in these stories?

The foundation for our persistent belief in stories, in spite of evidence suggesting a story is literally unbelievable, has perplexed researchers for many years. In one classic academic study, the behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner and several colleagues demonstrated that our innate need for superstition is deeply ingrained in our primal brains3. To make the point, Skinner studied one of the more powerful brains in the animal kingdom—the pigeon.

Skinner put hungry pigeons in a cage and dispensed food pellets to them every five seconds. Now, pigeons will naturally wander around any space looking for food, and will do so in predictably pigeon-like ways. One pigeon might step to the left and then step to the right; another pigeon might jump, land, and then jump again. Every five seconds, researchers released a food pellet. Quickly, the pigeons began to associate their random movements with the magically appearing food. After a few rounds of engaging in the same random activities and earning a series of food pellets, the pigeons developed an internal belief that one of their deliberate actions in the cage was actually causing food pellets to pop out of the feeder.

Amazingly, once a pigeon establishes its pellet dispensing ritual, it is exceedingly difficult to train the pigeon out of that particular “story.” Skinner attempted to give the pigeons evidence that their story was worthless (e.g., dispensing pellets at random times), but the pigeons continued with their story-based ways. Evidence has a hard time entering the decision-making process once a behavior has been established.

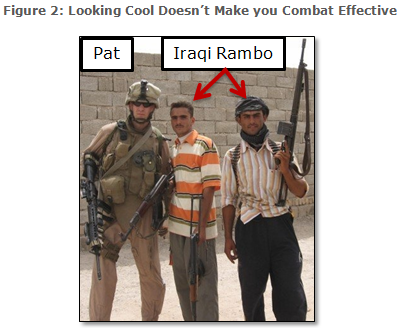

Pigeons aren’t the only animals suffering from “story bias.” We worked alongside Iraqi soldiers who wanted to believe they were Rambo. Many of the Iraqi soldiers felt it was imperative to strap ammunition rounds across their chest and rapidly shoot from the hip when engaged in combat. This Rambo-esque approach to a gunfight is absurd. The rounds across a fighter’s chest are exposed to the elements and the operator can never properly load them into their weapon system when they are needed most. Plus, shooting blindly from the hip is a great way to waste ammunition that rarely will hit the target. Being Rambo sounds cool in theory, but doesn’t work in practice. Marines, take a different, more evidence-based approach. Marines ensure all ammunition is loaded into clean functioning magazines that are stored on their person. They also spend countless hours loading and unloading magazines into their rifles to ensure the process is seamless in a combat environment. Finally, Marines take well-aimed shots at their enemy, focusing on the principles of marksmanship, even when they are amped up and in the middle of a firefight. A single effective round is worth 30 poorly aimed shots.

Do we see Rambo activity in financial markets where people believe a story, but disregard evidence? All the time. Take Wes’ uncle as an example. He is convinced that a Dallas Cowboys victory during the Thanksgiving Day football game is a great signal for the stock market. The logic is as follows: The Cowboys are “America’s Team” and if America’s Team is doing well, people are happier and they spend more money.

Of course, the “Dallas Cowboys” indicator is completely bogus. But there are many other stock market superstitions—sell in May and go away; let your winners run, but cut your losses; head and shoulders patterns; this is a stock-pickers’ market; invest in what you know; buy with a margin of safety; and so forth. Some of these stories are backed by evidence, others are not. The main point is that one’s investment process—or weapons handling process—should not be based on a story, but rather, on an evidence-based process that demonstrates robustness over time.

LESSON 3: Complacency Kills — Focus on Fundamentals

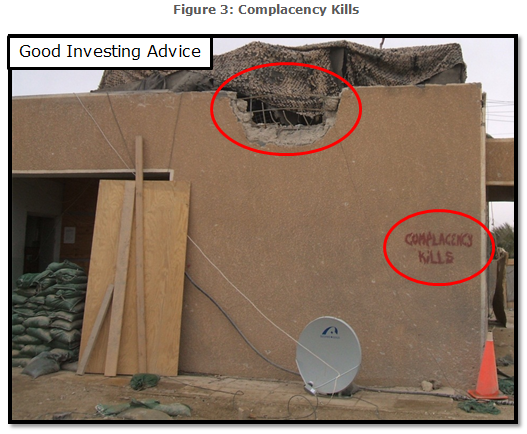

During Operation Iraqi Freedom, the message was everywhere. In the chow hall, on blast walls, in supply bays, and at checkpoints, “COMPLACENCY KILLS” was spray painted in bold, black, stencil letters. Figure 3 is a picture Wes took in Barwana, before heading out on a combat patrol. The reminder was seen by all Marines going on a patrol “outside the wire.” The large mortar shell damage above the “Complacency Kills” writing was a strong reminder of why this message was important.

The greatest enemy in a combat situation is not necessarily the enemy on the other side of the fence–it is ourselves! Keeping your weapon clean, your vehicle maintained, or your body awake, could be a life and death decision. And these were conscious decisions made every day. Fighting complacency is difficult. It requires discipline, patience, and relentless attention to detail. The fundamentals are boring, but they are often the most important.

Perhaps not surprisingly, complacency also kills in the financial world. When meeting with investors or family offices, we often see signs of complacency and a disregard for investing fundamentals. For example, investors sometimes do not focus on fees, and spend too much money on their investment advisor or end up buried in expensive bank products they don’t understand.

Investors also lose sight of the importance of taxes. Failing to stay vigilant to the effects of portfolio turnover or on the choice of investment vehicle can destroy returns. What is the real value of alpha for a taxable investor in a fund that earns a 10% return, but only 5% after tax? Perhaps a more tax-efficient fund, with lower turnover, makes the most sense? Amazingly, few individuals we speak with are fully aware of tax efficient alternatives like ETFs.

Another area where we see investor complacency is in allocations. Over time, allocations can get out of whack, as investors fail to maintain target allocations, or struggle to stay vigilant to portfolio rebalancing requirements. Investors can become overly concentrated in positions, or asset classes (such as being over allocated to cash). Also, in low- volatility environments, investors can be lured by the siren song of leverage. Nevertheless, as investors, it is important that we make consistently good decisions in order to make a return on our capital while not taking unnecessary risks.

We need to always focus on the fundamentals and avoid complacency. In the Marine Corps, the fundamentals are simple: Shoot, move, communicate. In investing, the fundamentals are also simple: maximize after-tax, after-fee, risk-adjusted returns. But just because something is simple, doesn’t necessarily mean it is easy. We need to religiously focus on the fundamentals. Remember, COMPLACENCY KILLS!

LESSON 4: Integrity is Everything — Do Things Right and Do the Right Things

Of the 14 Marine Corps leadership traits, integrity is probably the most important. The official definition is the following: “Uprightness of character and soundness of moral principles. The quality of truthfulness and honesty.”4 To both of us, having integrity means doing things right and doing the right thing.

Integrity can literally save lives, as Pat experienced.

An increasingly important part of Pat’s mission in Fallujah was to build fortified positions along key pieces of terrain. Such positions prevented bombmakers from “planting” their products, but of course, Marines can’t watch everything and every additional Marine sitting in a defensive position brings its own risk. You have to be brutally honest with yourself in terms of risk (Marines lost) versus reward (bad guys thwarted and / or killed).

Of course, in the “Fog of War” that honesty can be tough to preserve. A particular company officer, rightfully seeking to minimize bomb casualties as much as possible, requested that an oversight position that sat atop a highway overpass. While the position provided great visibility, you could also drive a suicide car bomb, literally, underneath the post. It simply didn’t make sense to take on that amount of risk, based on the evidence from prior experiences.

What started as a simple disagreement between officers quickly escalated into an expletive laden diatribe as to why Pat, as a junior Lieutenant, should “shut the hell up and build the post.”

Pat knew it was a bad idea and wasn’t the right thing to do. Building that post was nothing more than a star-spangled pinata for any terrorist to strike and Marines would needlessly die if constructed. Pat stood his ground, took the verbal beating, and built a post that he thought could withstand a potential attack. Throughout the entire episode, he was, in the back of his mind, running the odds of when, and how, he would be relieved of command for insubordination.

But that word never came. In fact, terrorists hit the post the day after it was built. The post took the blast and the overpass itself was completely destroyed. “Thank God we didn’t build it that way,” Pat muttered. “Corpsman!” (Marine-speak for for medic). “How many casualties did we take?” Pat dreaded the potential answer, but he had to know. It was his unit’s work and ultimately his call…

Pat’s Marines responded, “We’re good sir. No KIAs. Boys definitely got their bells rung, but they’ll be alright.”

It wasn’t easy for Pat to maintain his integrity, but his Marines are certainly glad he did. Doing things right and doing the right thing literally saved Marines’ lives.

In the context of finance, integrity doesn’t necessarily determine the difference between life and death, but it does have the same level of importance. Warren Buffett has said that integrity is everything: “In looking for people to hire, you look for three qualities: integrity, intelligence, and energy. And if they don’t have the first, the other two will kill you.” It is hard to disagree with Buffett or our experience in the Marines. Investors work extremely hard to earn their wealth and they are putting their families future on the line when they hire an investment advisor or asset manager. A broker may be encouraged to sell a specific product that isn’t necessarily good for his client, but the broker thinks to himself, “Aw, no big deal. Nobody will ever know and I need to get paid.” But it is a big deal. This is a breach of integrity and the broker isn’t doing the right thing. The client becomes worse off and the broker gets rich.

Conclusion:

Successful counterinsurgency campaigns are measured in decades. The foundation for a lasting peace requires years of listening, respecting, building, and empowering a local population to achieve their vision of a society. There are no shortcuts. There are no easy answers. The motto in the Marine Corps was as follows: “No better friend, no worse enemy.” From General to Private, Marines are expected to govern themselves with the highest standards and the purest of intentions day in and day out. Despite all of the new technology, tactics, and cutting edge gear, survival remains a struggle of willpower (destroying the enemy’s, while simultaneously controlling and channeling our own).

Most shortcuts in finance are ill-conceived at their best and outright illegal at their worst. History is replete with examples of those who pursue shortcuts in this business and those who keep it simple, follow their model, and stick to the plan (Buffett and Vanguard’s Bogle are personal favorites). Like most things in life, things worth doing take hard work, persistence, and a clear plan.

We hope that our look back on the lessons learned in the Marine Corps informs how we carry ourselves and our business. We are thankful to have served with such courageous men and women that tried to make a small corner of the world a better place. The world of finance will always change, but the lessons learned in the military will serve us for years to come.

Semper Fidelis.

On this Memorial Day, remember all those who gave the ultimate sacrifice. Freedom isn’t free and the United States Constitution, although imperfect, is still worth fighting for.

Written by Wesley R. Gray and Patrick R. Cleary

Footnotes:

- As of 4/30/2015

- John Mueller, 2008, Dead and deader, Los Angeles Times, pg. M7. http://goo.gl/lsXck0

- B.F. Skinner, 1948, Superstition in the Pigeon, Journal of Experimental Psychology 38, p. 168-172.

- MCRP 6-11B, Marine Corps Values: Appendix A, B.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.