In this piece I examine various way in which an investor can think about their active market timing decisions, often labeled with the innocuous term “rebalancing.”

Rebalancing a portfolio is the finance version of “eat your vegetables” — the advice is taken as gospel, but very few people question the advice and/or how to implement the advice. But do the so-called sophisticated market participants (i.e., traditional advisers, robo-advisers, and target date funds) who tout rebalancing as a valuable service really think through their rebalancing process? Have these “passive” investors, who are engaged in selling an active market timing service, ever really considered how and why they rebalance the way they do? Many of these providers have certainly carefully considered the costs and benefits of their rebalancing process, but having reviewed many of the rebalancing services embedded in investment services/products available to the public, my guess is that some of these providers have not thought too deeply about rebalancing.

Why are rebalance decisions so important?

To reiterate, rebalancing is an active market timing consideration and should not be a decision that is taken lightly. The decision is just as active as deciding between buying a passive market-cap weighted index or a portfolio of concentrated value and momentum stocks. And like all active decisions, one should carefully consider the evidence and the actions of other market participants when rebalancing a portfolio. Rebalancing decisions and processes don’t need to be complex, but they do need to be considered.

If You Rebalance, You Are an Active Investor

There has been a lot of ink spilled in discussion about passive index investing, but in this sense passive index investing generally means a market cap weighted stock portfolio…but not very many people own only a market cap weighted stock portfolio (and far fewer probably own a global market cap weighted stock portfolio which is the only true market cap weighted stock portfolio but that is a discussion for another day). Most people probably own a portfolio comprised of stocks and bonds. The mix of stock and bonds in their portfolios is probably set by either their risk tolerance, time to retirement, or some similar planning concept. The resulting asset allocation is often referred to as their target portfolio (strategic allocation or policy portfolio).

One thing I find very interesting is that their portfolio spends very little time actually at the target allocation because the price of stocks and bonds is ever changing. Therefore, any asset allocation deviation from the target allocation is an active (i.e., market timing) decision.

The deviation from the target allocation can be made on accident (prices changed and I haven’t rebalanced yet) or on purpose, but the end result is the same — any deviation from the target allocation is an explicit market timing bet in the portfolio. For example, if you started the year at your target allocation of 50% stocks and 50% bonds and stocks outperformed bonds by 10% in the first week, then your portfolio is approximately 55% stocks and 45% bonds. If you decide not to rebalance your portfolio (tolerance bands haven’t been breached or it isn’t the end of the quarter or year) you are now making (a small) market timing bet that stocks are likely to outperform bonds until your next rebalance. If you do rebalance the portfolio, you are making a small timing bet that stocks are likely to underperform bonds.

Common Rebalancing Algorithms

With this (market timing) perspective of rebalancing in mind, let’s quickly review the most common rebalancing decision algorithms 1) calendar based or 2) tolerance range (tolerance band) based.

- Calendar based rebalancing means that the adviser rebalances a portfolio back to the strategic (or target) allocation at a set calendar frequency (monthly, quarterly or annually) and some even tout doing this on a real-time daily basis.

- Tolerance range rebalancing means that the investor has a predefined range of variation in asset allocation that is acceptable, but once an asset breaches the upper or lower bound of the range the portfolio is then rebalanced back to the strategic (or target) allocation. This may occur as frequently as daily or weekly and as infrequently as biannually (or even longer).

But does the generic rebalancing of a portfolio actually add value? This research paper by Vanguard points to the conclusion that there is no optimal rebalancing algorithm when calendar or tolerance ranges are considered.

A recent research paper by Baker, Dieschbourg, McIntyre and Muralidhar also found a similar conclusion that traditional rebalancing algorithms didn’t add much value (and actually hurt from the perspective of portfolio drawdowns). In addition, they went a step further and provided some specific market timing algorithms that in isolation and when combined provided additional returns and reduced drawdowns but not standard deviations.

Let’s take a more in-depth look at their paper.

The Mythology of Rebalancing Overview

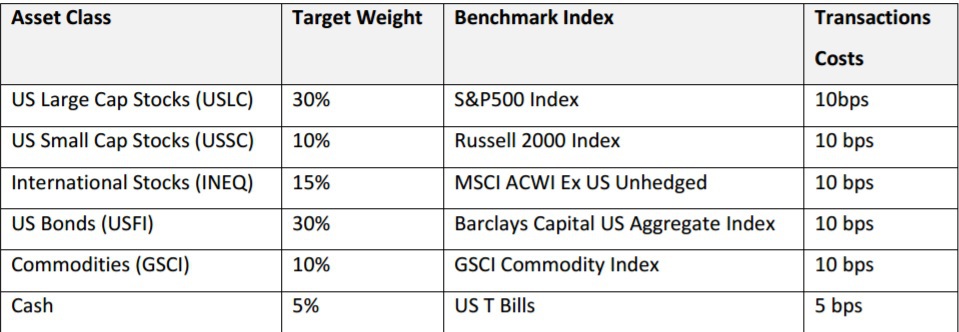

The analysis in this paper uses daily data from 1/1/2000 through 12/31/14 for the following asset classes:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

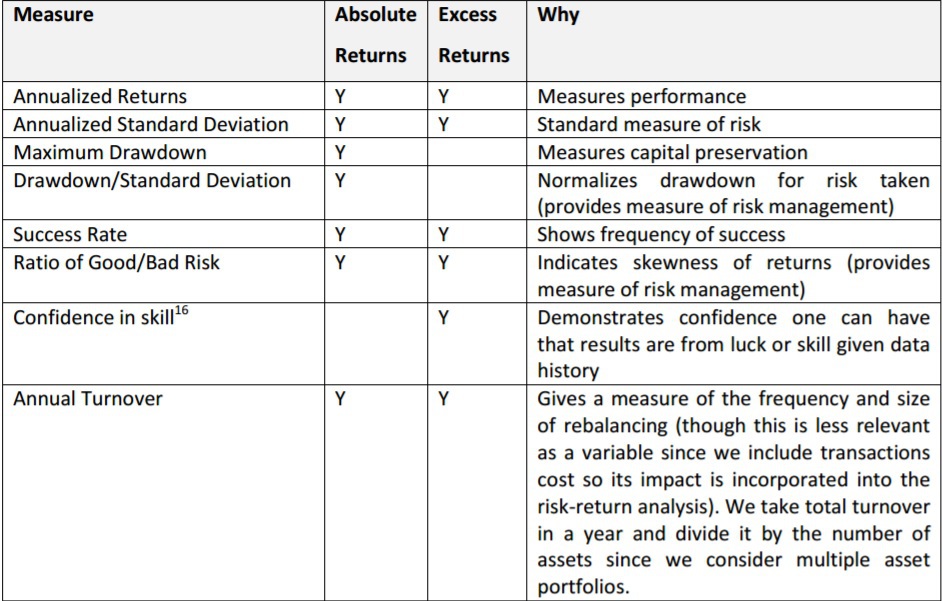

They used the following to judge the effectiveness of the rebalancing algorithms:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Finally, the looked at the following standard rebalancing algorithms:

- Monthly

- Quarterly

- 3% Tolerance Band

- 5% Tolerance Band

- Volatility adjusted Tolerance Range (Bonds & Cash at 3% range all others at 5%)

- Naive Target Date Fund (reduce stock allocation by 1% per year and increase bond allocation by 1% per year)

- Benchmark – this is an unrealistic, costless and continuously rebalanced portfolio back to the target weights.

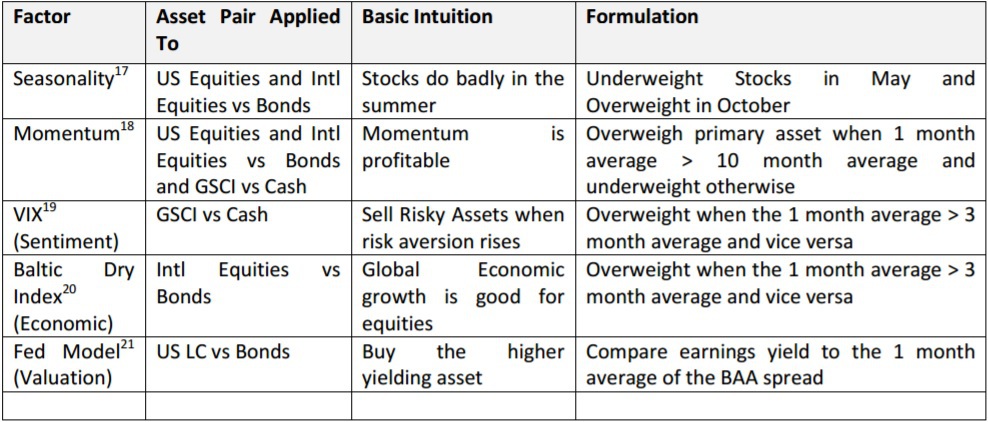

However, with the perspective that all rebalancing decisions are active market timing decisions, they evaluate the the following market timing algorithms in lieu of traditional rebalancing algorithms:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

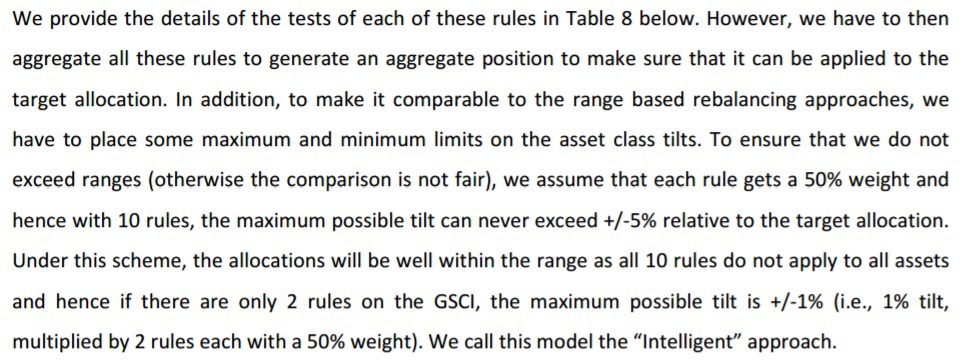

The following excerpt from their paper explains how they apply the rules and which asset class to underweight and which to overweight:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

So do the explicit market timing algorithms (called “Intelligent Rebalancing” by the authors) outperform traditional rebalancing algorithms (called “Naive Rebalancing” by the authors)?

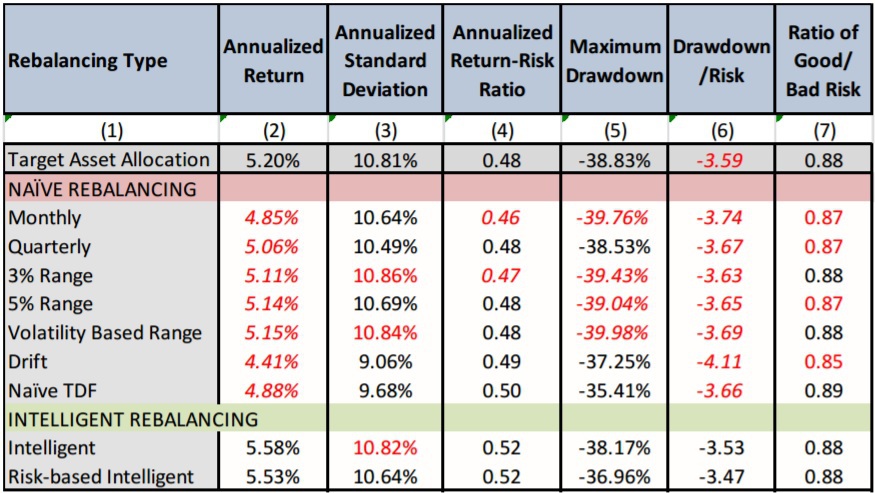

Here are the results from the paper:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

This table shows that all of the “naive rebalancing” algorithms under-perform the benchmark portfolio from a return perspective. However, the “naive rebalancing” algorithms do reduce the standard deviation of portfolios, thus keeping the Sharpe ratio on par with the benchmark portfolio.

One interesting result of the “naive rebalancing” algorithms is the increase in the maximum drawdowns versus the benchmark portfolio (except Naive TDF which is because the Naive TDF changes its assest allocation through time).

The “Intelligent Rebalancing” algorithms improve portfolio returns but do so at the cost of an increase in the standard deviation of the portfolio. However, the Sharpe ratio of the “intelligent rebalancing” portfolios are still improved versus the benchmark portfolio. In addition, the results show that the “Intelligent Rebalancing” algorithms mildly reduce maximum drawdowns versus the benchmark portfolio.

Thoughts on the Results

I thought this was a really interesting paper and it made me think a lot about some assumptions of mine that I hadn’t really questioned before. In no particular order are some of my thoughts following reading this paper:

- This paper deals with a fairly limited data history but high frequency (daily) of data. What do the results look like using a longer data set with monthly data (I will look at this in a future blog post)?

- The authors use valuation market timing decisions (Fed Model) that has worked well during a brief set of history, but Cliff Asness shows fails theortically and John Hussman shows fails emprically.

- Wes has shown in numerous posts just how hard valuation market timing is, but this article makes it look easy. I view the claim of this paper suspiciously.

- Seasonality is an interesting anomaly, but I wish the authors would have stuck to factors that have more academic support like value, momentum or carry when it came to making their “intelligent rebalancing” algorithms.

- There are a handful of moving pieces and they’re looking at data over a very short time period — even though the authors highlight the Asness quote that you need 45 years of data when it comes to understanding asset class costs/benefits.

- I think overfitting might be a major issue to consider here. They need a lot more data and more theory.

- My guess is their trend rule (they call it “momentum”) rule drives all statistical differences. The Alpha Architect team has looked at the other stuff in older research projects (e.g., vix, baltic dry, valuation, and so forth) and came to the conclusion they weren’t very robust.

Finally, overall I understand the author’s arguments that if you are engaged in high frequency rebalancing and wasting a lot of $ on taxes/frictional, you should rethink your rebalance process. However, at some level, rebalancing is important if you want your portfolio to benefit from the rebalancing bonus (info here) and desire structural diversification. For example, if your equity blows up 50% and your managed futures are up 100%, you should consider rebalancing, unless, of course, you have no problem essentially owning a managed futures fund as your sole investment. Also, if you are deploying any sort of trend-following overlay, the risk of “rebalancing into a falling knife” is minimized. For example, if stocks go down 20% — and trend breaks — you don’t automatically sell your winning assets (e.g. bonds) and turn around and buy stocks — maybe you allocate some bond proceeds to the “stock bucket” and deploy that capital when the trend is positive again. These ideas we’ll explore in future posts.

If you made it this far, I suggest you read the paper and question your rebalancing algorithms too…it will probably be worth it.

The Mythology of Rebalancing: A Random Walk Down Performance and Risk Management

- Brian Baker, Mike Dieschbourg, Damian McIntyre and Arun Muralidhar

- A version of the paper can be found here.

- Want a summary of academic papers with alpha? Check out our Academic Research Recap Category.

Abstract:

There has been a rapid growth in retail investing with assets increasingly going into roboadvisors and target date funds. One of the appealing aspects of these platforms and products is that they delegate all investment decisions to the asset manager (who is believed to be more sophisticated) and away from the asset owner (who is typically unsophisticated). The appeal of these products and platforms is driven by their ability to make effective forecasts of assets, derive an effective asset allocation, and then to rebalance the portfolios on a periodic basis to this target asset allocation. In this paper, we will just focus on the robo-advisors and argue that one key activity underlying these platforms and even practiced very broadly in institutional investing and defined contribution funds, naïve rebalancing, is predicated on bad theory and myths and fails the key test of whether it truly improves performance and/or risk management. We will demonstrate that many previous studies of rebalancing examine this issue from a simplistic perspective of a two-asset portfolio and a simple measure of risk, volatility.

When we examine these strategies from the perspective of a multi-asset portfolio and a broader set of risk statistics (that a sophisticated investor would apply), then these naïve rebalancing strategies are nothing more than a form of poor market timing and the performance is a coin-toss and the risk profile of the portfolio is typically worsened. Once these flaws of naïve rebalancing are exposed, we suggest that investors would be well advised to adopt a more intelligent form of rebalancing, where an intelligent analysis is conducted of the relative attractiveness of assets to then set allocations within a client’s policy ranges. This approach has a higher likelihood of improving performance and risk management and the ideas to implement such a program are in the public domain.

About the Author: Andrew Miller

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.