The academic research has generally found valuations, such as the earnings yield (E/P) (or the CAPE 10 earnings yield) and valuation spreads, have predictive value in terms of future returns. The higher the earnings yield, the higher the expected return, and the larger the spread in valuations between growth and value stocks, the larger the future value premium is likely to be in the future.(1)

This relationship holds across asset classes, not just for stocks. For example, the 2007 study, “Does Predicting the Value Premium Earn Abnormal Returns?” by Jim Davis of DFA found that, despite book-to-market spreads containing information as to future returns, style-timing rules did not generate high average returns because the signals are “too noisy.” In other words, while a wider spread in valuations predicts a higher value premium, it doesn’t provide enough information to offer a profitable timing signal — allowing investors to successfully switch between value and growth strategies.

Further support that valuation spreads provide information comes from the October 2017 study, “Value Timing: Risk and Return Across Asset Classes,” authored by Fahiz M. Baba Yara, Martijn Boons and Andrea Tamoni.

The authors found the following:

Returns to value strategies in individual equities, commodities, currencies, global government bonds and stock indexes are predictable by the value spread…In all asset classes, a standard deviation increase in the value spread predicts an increase in expected value return in the same order of magnitude (or more) as the unconditional value premium.

Exploring Deep Value

AQR’s Cliff Asness, John Liew, Lasse Heje Pedersen and Ashwin Thapar contribute to the literature on the value premium with their November 2017 study, “Deep Value.” Defining “deep value” as episodes where the valuation spread between cheap and expensive securities is wide relative to its history, they examined it across global individual equities, equity index futures, currencies and global bonds. Depending on the asset class, the data sample extends as far back as 1926.

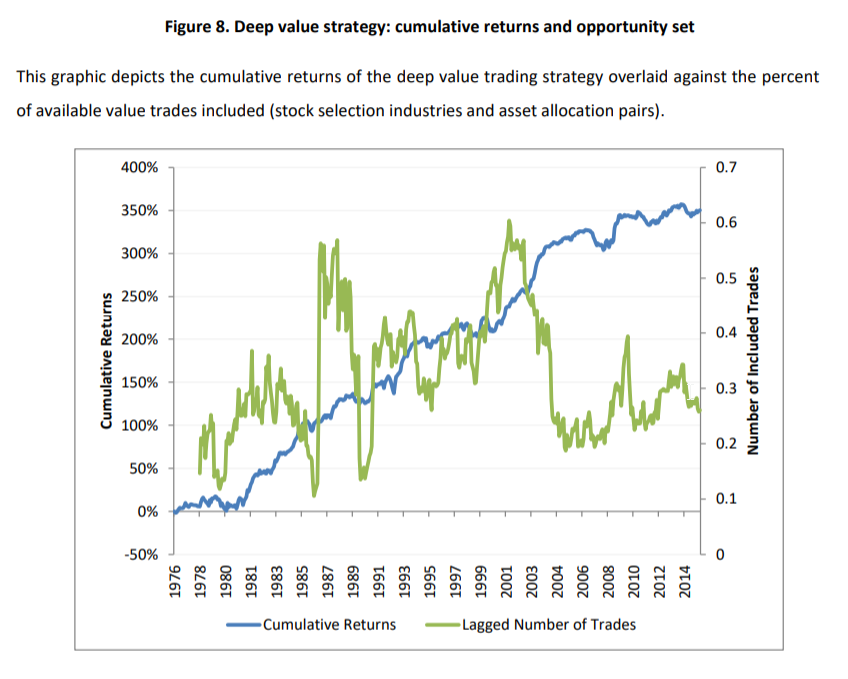

Here are the cumulative returns for one of the deep value strategies outlined in the paper:

The following is a summary of their findings:

- Consistent with prior research, global assets that look cheaper based on their valuation ratios perform better on average than expensive assets and value spreads predict returns to value strategies. Returns to value strategies are particularly high during “deep value episodes,” defined as top quintile value spreads. For example, when the U.S. value spread is in the 5th quintile, the value strategy returns an average of 1.2 percent, and when the value spread is in the bottom 1st quintile, the premium is 0.0 percent. As with any asset, in terms of expected returns, valuations matter.

- For each of the asset allocation strategies the study examined (equity indices, fixed income, currencies), predictive regressions show a positive and significant relationship between current value spreads and excess return in the next 12 months to the standard and intra-industry value strategies. Also, when all three of the asset classes are pooled together, the results remain strong. Finally, when they pooled across four stock regions and the three asset classes, they had the strongest results, demonstrating the robustness of deep value.

- Long-short value portfolios have average market betas close to zero. However, their betas are negative during deep-value episodes. Deep-value investing in stocks appears to hedge market risk, a puzzle for the CAPM model. Thus, value is not compensation for market risk. Instead, it reflects another unique/independent risk factor.

- While value portfolios obviously load on a global value factor, the loading is larger during deep-value episodes.

- Value stocks experience weak growth, especially during deep-value episodes, providing a risk-based explanation for the value premium. During deep value episodes, the earnings of cheap stocks have been particularly weak versus those of expensive stocks leading up to the event, and this relative earnings weakness continues after the event.

- Analysts’ earnings forecasts for value stocks, versus those of growth stocks, tend to be revised downward. And the deterioration of analyst forecasts is greater leading into deep-value events and continues for about a year, after which it starts to partly reverse, providing support for a behavioral explanation accounting for at least a portion of the value premium.

- Investors overreact to past returns, again providing a behavioral explanation for the value premium. Value stocks face more selling pressure than growth stocks, particularly leading into deep-value events, and continues for five years, although it subsides after a year. Said another way, growth stocks exhibit bubbles and value stocks exhibit “anti-bubbles.” Furthermore, limits to arbitrage prevent correction of mispricings — bid-ask spreads for the value portfolio tend to widen, the cost of short-selling growth stocks (which is necessary for a long-short value strategy) is higher than normal, and the volatility of the long-short value portfolio is higher than normal.

- Value “arbitrage” increases around deep value episodes. Specifically, short interest of growth stocks is higher during deep-value episodes, net equity issuance is greater for growth stocks than value stocks (consistent with the idea that managers of overvalued stocks are more likely to issue shares and less likely to repurchase shares, and that this effect is stronger after deep value events), and value stocks are more likely to be acquired in a merger than growth stocks (especially in years following deep-value events, consistent with the notion that acquirers finds these stocks cheap). Specifically, the chance that a value stock is bought in any given month is 0.26 percent, whereas the corresponding number for growth stocks is only 0.15 percent.

- The momentum of deep-value assets is even more negative than that of untimed value, an intuitive result because deep-value assets tend to have particularly negative past returns.

- Deep-value opportunities cluster: wide value spreads tend to occur about the same time across many of the asset classes and securities. Two notable clusters of deep-value opportunities occurred in conjunction with the tech bubble in the late 1990s and the 2008 global financial crisis. The authors write:

This clustering could be explained by either a time-varying global risk premium to value or bouts of market-wide irrationality together with widening limits to arbitrage. Interestingly, the global deep value strategy performs better following times of abundant deep value events.”

The authors concluded:

Put together, all of these observations provide insight into the source of the value premium. The evidence rejects the notion that price changes are pure noise. In contrast, stock prices and deep value episodes appear to be driven by mix of rational and behavioral factors.

Summary

Consistent with rational (that is, economic) explanations for the value premium, the authors of the “Deep Value” study found that value stocks have cheap prices for a reason — their earnings fundamentals clearly deteriorate over time, especially during deep-value events. And assets that do poorly in bad times should command a large premium. However, their results present a puzzle from a rational perspective because value strategies have negative market betas, especially during deep-value events when the returns are particularly high. Their findings are consistent with behavioral theories regarding over-extrapolation of past returns, but not with theories of over-reaction to fundamentals. They also found that sentiment-driven investors sell cheap value stocks based on a documented negative tone of news, resulting in selling pressure for value stocks relative to growth stocks. Because this selling pressure is driven by past returns, not past fundamentals, it provides support for the behavioral theory of investors’ over-extrapolation of past returns. Finally, they found that limits to arbitrage exist for deep-value portfolios due to high transaction costs and short-sale costs (though arbitrage appears to exist in the sense of elevated short interest, and firms appear to act as “arbitrageurs of last resort” in their decisions to conduct new issues, share repurchases, and corporate take-overs.

For investors, the important message is that value strategies require great patience and discipline, as the greatest returns are earned only by those willing and able to hold value assets after periods of relatively poor performance and through difficult economic times.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Alpha Architect looked at timing value spreads with the EBIT/TEV ratio and found mixed results. |

|---|

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.