Proxies and Databases in Financial Misconduct Research

- Jonathan M. Karpoff, Allison Koester, D. Scott Lee and Gerald S. Martin

- The Accounting Review

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category

What are the research questions?

The investigation of financial fraud or misconduct is a mainstream research topic yielding over 150 articles in the literature to date. The availability and ease of access to four well-known databases used in this research has contributed to the popularity and impact of the topic. The four databases and their associated proxies used to identify misconduct events includes:

- GAO (the Government Accountability Office; Proxy used – Restatement Announcements)

- AA (Audit Analytics; Proxy used – Restatement Announcements)

- SCA (the Stanford Securities Class Action Clearinghouse; Proxy used – Securities Class Action Lawsuits)

- CFRM (UC-Berkeley’s Center for Financial Reporting & Management; Proxy used – SEC’s Accounting & Enforcement Releases).

1. Are the results across the four databases, frequently used to identify and investigate financial fraud or misconduct, subject to systematic biases or problems with replication of results across studies?

2. If so, why do the samples drawn from different databases produce different empirical results? Are there features contained in each database that explain the differences? What is the economic importance of those features?

What are the Academic Insights?

1. YES. The authors report that the events identified as financial fraud in the four databases are not close substitutes. The four databases exhibit systematic differences in the events identified as misconduct or fraud and systematic differences in the events that each database eliminates as misconduct or fraud. For example, empirical results are replicated 42% of the time when random samples are drawn and comparisons made among databases.

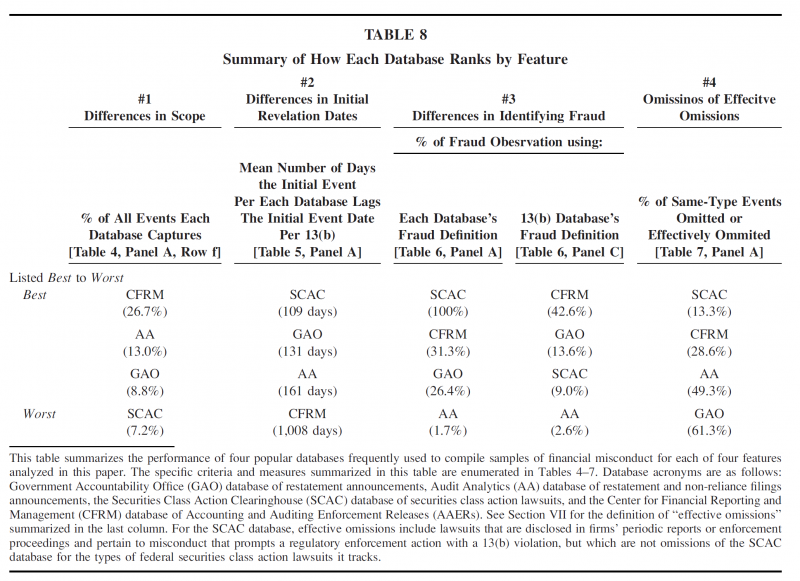

2. YES. Four features associated with each database include the scope of coverage in the database, the revelation dates used, the identification of fraudulent events or proxies, and omissions of events.

Proxy: Each database defines “fraud” and “misconduct” in different ways.

Scope: By design, each database gathers information on only a portion of informational events that would be considered a “case of financial misconduct”. Each case actually consists of a myriad of events from company press releases, regulatory investigations, regulatory enforcement releases, restatement announcements, class action lawsuits, settlements and so on. None of the four databases collects data on the entire series of events but, purposefully, capture a single proxy such as restatement announcements or securities class action lawsuits.

Revelation date: Consistent with a focus on different proxies for the misconduct event, it follows that the initial revelation date will vary across databases. Differences in initial dates therefore, affect the measurement of the stock market reactions or the size of changes in firm characteristics around the event. The authors report that the initial revelation date discrepancies indicate the market reaction is understated by 30.6% to 80.8%.

Omissions: Three of the databases were found to omit significant numbers of events they purport to capture. Omitted firms may introduce any number of biases, for example if these firms are assigned to a control group.

Why does it matter?

In addition to insights regarding issues of corporate governance, this stream of research has provided significant insight into the workings of financial reporting, financial regulation and policy questions. The databases that have emerged supporting and informing this research stream, while useful and accurate within their scope, exhibit material differences. The results presented in this article indicate that empirical inferences drawn across studies are sensitive to specific features of the individual database and the proxy used to identify financial misconduct.

A major contribution of this article is, however, a detailed discussion of each database with respect to the four features identified by the authors and guidelines for mitigating biases that may result. The discussion the authors provide in the conclusion of the article is a must-read for researchers utilizing these sources of data.

The most important chart from the paper

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Abstract

An extensive literature examines the causes and effects of financial misconduct based on samples drawn from four popular databases that identify restatements, securities class action lawsuits, and Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAERs). We show that the results from empirical tests can depend on which database is accessed. To examine the causes of such discrepancies, we compare the information in each database to a detailed sample of 1,243 case histories in which regulators brought enforcement actions for financial misrepresentation. These comparisons allow us to identify, measure, and estimate the economic importance of four features of each database that affect inferences from empirical tests. We show the extent to which each database is subject to these concerns and offer suggestions for researchers using these databases.

About the Author: Tommi Johnsen, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.