The carry factor is the tendency for higher-yielding assets to provide higher returns than lower-yielding assets — it is a cousin to the value factor, which is the tendency for relatively cheap assets to outperform relatively expensive ones. A simplified description of carry is the return an investor receives (net of financing) if prices remain the same. The classic application is in currencies — specifically, going long currencies of countries with the highest interest rates and short those with the lowest.

While currency carry has been both a well-known and a profitable strategy over several decades, the carry trade is a pervasive phenomenon, having been profitable across asset classes. For example, the 2015 study “Carry” by Ralph Koijen, Tobias Moskowitz, Lasse Pedersen and Evert Vrugt found the following:

While the concept of ‘carry’ has been applied almost exclusively to currencies, it’s a more general phenomenon that can be applied to any asset.

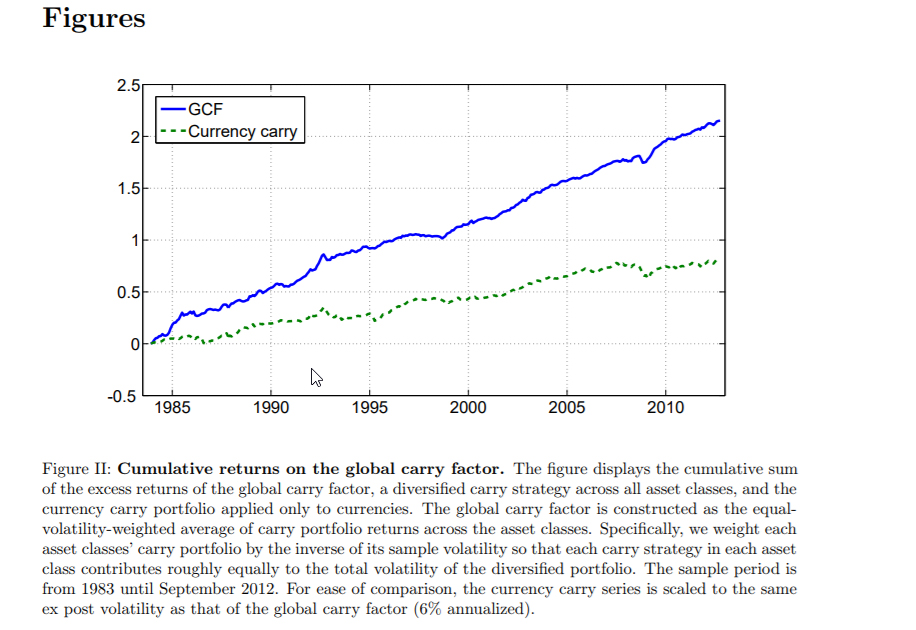

The chart below summarizes their core finding:

They defined carry as the expected return on an asset assuming its price does not change — that is, stock prices do not change, currency yields do not change, bond yields do not change, and spot commodity prices remain unchanged. Thus, for equities, the carry trade is defined by the dividend yield (the strategy is going long countries with high dividend yield and short countries with low dividend yield); for bonds, it is determined by the term structure of rates; and for commodities, it is determined by the roll return (the difference between spot rates and future rates).

More Evidence on the Carry Trade

The authors found that a carry trade that goes long high-carry assets and shorts low-carry assets earns significant returns in each asset class with an annualized Sharpe ratio of 0.7 on average. Further, a diversified portfolio of carry strategies across all asset classes earns a Sharpe ratio of 1.2. They also found that carry predicts future returns in every asset class with a positive coefficient, but the magnitude of the predictive coefficient differs across asset classes.

Mohammadreza Tavakoli Baghdadabad and Girijasankar Mallik contribute to the literature on the carry trade with their study, “Global Risk Co-Moments and Carry Trade Strategy,” which appears in the Spring 2018 issue of The Journal of Fixed Income. Their focus was on determining if the profitability of the carry trade could be explained by global risk factors.

They state:

A rational investor is theoretically concerned about variables influencing the investment opportunity set and tends to hedge against unexpected variations in market co-moments, stimulating risk-averse agents to demand a currency that hedges against these co-moments.

The demand for hedging properties leads to lower returns. Given this hypothesis, they investigated whether the sensitivity of excess returns to global co-moments in skewness (a measure of the asymmetry in a statistical distribution) and kurtosis (a measure of the tails of a frequency distribution when compared with a normal distribution) is able to rationalize currency portfolio returns in an asset-pricing framework. Specifically, they examined whether global co-skewness and co-kurtosis (the degree to which asset prices move together) are important drivers of risk premiums in explaining the cross-section of carry trade returns.

Their data sample included 52 currencies (22 developed and 30 emerging markets). Their equity sample excluded the smallest 5 percent of stocks by market capitalization. The currency portfolios were split into quintiles. The study covered the period from 1994 through 2016.

Baghdadabad and Mallik found that sorting currencies into the global co-moment betas leads to a large difference in currency portfolio returns. The result is a significant negative relation between high-interest-rate currencies and global co-skewness that delivers low returns during instances of unexpectedly high co-skewness when low-interest-rate currencies are used as a hedge by earning positive returns. Thus, the carry trade performs poorly in times of market depression. Therefore, the high returns to the carry trade can be rationalized from the standard asset-pricing perspective as compensation for time-varying risk. Specifically, they found a monotonically increasing pattern in average returns and Sharpe ratios when moving from portfolio 1 (lowest yielding) to portfolio 5 (highest yielding). The unconditional average excess returns from holding an equal-weighted currency portfolio was 2.9 percent (and 0.6 percent for a subsample of 14 developed countries).

Also of interest was that the authors found that the pricing power of their co-moments helped explain the cross-section of returns for size and book-to-market strategies, providing risk-based explanations for them. In addition, they found their co-moments are correlated with risk factors that show global financial market liquidity (including bid-ask spreads, the spread between three-month euro interbank deposit and three-month Treasury bills, and a global liquidity measure).

The Carry Factor is Implementable and Intuitive

As my co-author, Andrew Berkin, and I discuss in “Your Complete Guide to Factor-Based Investing,” an important issue to consider is whether a strategy is actually implementable — results from studies may not survive real-world transaction costs, raising the question of whether the carry strategy is implementable.

Implementable

The markets in which the carry trade invests are among the most liquid in the world, including foreign exchange markets, government bond markets and commodities futures. To implement the carry trade, investors do not need to venture into thinly traded, illiquid markets such as those of micro-cap stocks or emerging market currencies. Thus, trading costs are low. Importantly, the correlations among carry strategies are low. This reduces the volatility of a diversified portfolio substantially and mitigates the risks of fat tails associated with all carry trades. The result is that while all individual carry strategies have excess kurtosis (fat tails), a carry strategy diversified across all asset classes has skewness close to zero and thinner tails than a diversified passive exposure to the global market portfolio.

Another issue raised in our book is whether the strategy is supported by intuitive explanations.

Intuitive

Carry has a simple intuitive rationale, as prices balance out the supply and demand for capital across markets. High interest rates can signal an excess demand for capital not met by local savings while low rates suggest an excess supply. Traditional economic theory, what is known as uncovered interest parity (UIP), states that there should be an equality of expected returns on otherwise comparable financial assets denominated in two different currencies — rate differentials would be offset by currency appreciation or depreciation such that investor returns would be the same across markets. However, there is overwhelming empirical evidence against the UIP theory. Thus, we have what is known as the UIP puzzle.

The UIP anomaly may be due to the presence of non-profit-seeking market participants, such as central banks and corporate hedgers, introducing inefficiencies to currency markets and interest rates. The strategy is not without risk, as there can be instances when capital flees to low-yielding “safe havens” — providing a simple, risk-based explanation for the carry premium with the positive performance over the long term being compensation for potential losses in bad economic environments. In other words, currencies that appreciate when the stock market falls might be a good investment because they provide valuable insurance against unfavorable fluctuations in equity markets. On the other hand, currencies that depreciate in times of poor stock-market performance tend to further destabilize investors’ positions and should therefore offer a premium for that risk. The theory is supported by the evidence, which I’ll review.

Carry Factor Theory/Evidence

Victoria Atanasov and Thomas Nitschka, authors of the 2015 study “Foreign Currency Returns and Systematic Risks,” found “a strong relation between currencies’ average returns and their sensitivities to cash-flow shocks in equity markets. High forward-discount currencies react strongly to stock-market cash flows while low forward-discount currencies are much more resilient in this regard.” They explain:

Basic finance theory suggests that high forward-discount currencies depreciate when the ‘home’ stock market receives bad cash-flow news that is associated with capital losses, whereas low forward-discount currencies appreciate under the same conditions. Thus, holding high forward-discount currencies is risky for a stockholder, while investing in low forward-discount currencies can provide him a hedge.

They found their model “can explain between 81% and 87% in total variation in average returns on foreign-currency portfolios.” They concluded:

The free-lunch hypothesis on foreign-exchange markets is strongly rejected by the data. We argue that making money on currency investments is tightly linked to bad news about future dividend payments on stock markets: high forward-discount currencies load more on cash-flow risk than their low forward-discount counterparts.

Martin Lettau, Matteo Maggiori and Michael Weber, authors of the study “Conditional Risk Premia in Currency Markets and Other Asset Classes,” also provide a risk-based explanation for the success of the carry trade. Their study covered the period from January 1974 through March 2010 and more than 50 currencies. The authors found that “while high yield currencies have higher betas (exposure to equity market risk) than lower yield currencies, the difference in betas is too small to account for the observed spread in currency returns.” However, because investors are known to exhibit downside-risk aversion, they extended their research to include a downside risk capital asset pricing model, which they call DR-CAPM. They found that the DR-CAPM does price the cross section of currency returns. Specifically, they found that while the overall correlation of the carry to trade to beta is 0.14, and is statistically significant, most of the unconditional correlation is due to the downstate. Conditional on the downstate, the correlation increases to 0.33 while it is only 0.03 in the upstate. They also found that while the correlation of high-yield currencies with market returns is a decreasing function of market returns, the opposite is true for low-yield currencies (the low-yielding currencies benefit from a flight to quality in bad times). They found that the DR-CAPM explained about 85 percent of the cross-section of returns.

The authors concluded that “high yield currencies earn higher excess returns than low yield currencies because their co-movement with aggregate market returns is stronger conditional on bad market returns than it is conditional on good market returns.” They also found that this downside risk premium is a feature of not only of currencies, but also of equities, commodities and sovereign bonds. Their findings are aligned with standard asset pricing theory, which posits that assets that tend to perform poorly in bad times should carry risk premiums.

These risk-based findings are consistent with other research. For example, Charlotte Christiansen, Angelo Ranaldo, and Paul Söderlind, authors of the 2011 study “The Time-Varying Systematic Risk of Carry Trade Strategies,” found that while the carry trade strategy has been quite successful, it has high exposure to the stock market and is mean-reverting in regimes of high foreign exchange volatility. In addition, carry experiences what can be called crashes — it comes with the risk of large losses (fat tails) that tend to occur at the same time equity markets are crashing.

Lucio Sarno, Paul Schneider and Christian Wagner, authors of the 2011 study, “Properties of Foreign Exchange Risk Premiums,” also concluded that risk premiums explain the success of the carry trade.

They found:

- The time-varying excess returns are compensation for both currency risk and interest rate risk — high-interest-rate currencies depreciate on average when domestic consumption growth is low (such as in 2008) while low-interest-rate currencies appreciate under the same conditions.

- Financial and macroeconomic variables are important drivers of the foreign exchange risk premium.

- Expected excess returns are related to global risk aversion — in times of global market uncertainty and higher funding liquidity constraints, investors demand higher risk premiums on high-yield currencies while they accept lower (or more negative) risk premiums on low-yield currencies. This supports flight-to-quality and flight-to-liquidity arguments for the risk premium in the carry trade.

- Expected excess returns are countercyclical to the state of the U.S. economy.

The authors concluded that, “foreign exchange risk premiums are driven by global risk perception and macroeconomic variables in a way that is consistent with economic intuition.”

Hanno Lustig, Nikolai Roussanov and Adrein Verdelhan, authors of the 2011 study “Common Risk Factors in Currency Markets,” also found that the carry trade premium is related to changes in global equity market volatility — high-interest-rate (low-interest-rate) currencies tend to depreciate (appreciate) when global equity volatility is high. They concluded that the price of volatility is negative (and statistically significant). In other words, by investing in high-interest-rate currencies and borrowing low-interest-rate currencies, U.S. investors are loading up on global risk.

(1)Lukas Menkhoff, Lucio Sarno, Maik Schmeling and Andreas Schrimpf, authors of the 2011 study “Carry Trades and Global Foreign Exchange Volatility,” found that more than 90 percent of the cross-sectional excess returns from the carry trade were explained by foreign exchange volatility — evidence that the excess return is a result of an economically meaningful risk-return relationship. In times of heightened volatility, lower-interest-rate currencies offer insurance, because their exchange rate appreciates in response to an adverse global shock. Thus, these “safe havens” (such as the Swiss franc) earn a lower risk premium than others perceived as riskier. Safe-haven currencies tend to appreciate when market risk and illiquidity increase.

Finally, the authors of the aforementioned 2015 study, “Carry,” found that despite the high Sharpe ratios — an individual average annualized Sharpe ratio of 0.7 and Sharpe ratio of 1.2 for a diversified portfolio across asset classes — carry strategies are far from riskless as all individual carry strategies have excess kurtosis (fat tails), exhibiting sizeable declines for extended periods of time. These periods coincide with bad states of the global economy (such as August 1972 to September 1975, March 1980 to June 1982, and August 2008 to February 2009) — recessions and liquidity crises. In other words, carry strategies in almost all asset classes are positively exposed to global liquidity shocks and negatively exposed to volatility risk. Thus, carry strategies tend to incur losses during times of worsened liquidity and heightened volatility (when stocks do poorly). However, an exception is the carry trade across U.S. Treasuries of different maturities, which has opposite loadings on liquidity and volatility risks, thus making it a hedge against the other carry strategies, dampening the risk of a diversified carry strategy.

The authors also noted that the risks of carry can be mitigated in a portfolio where carry is applied across many asset groups. The concept of carry, when applied more broadly across asset groups beyond currencies, is a clear example of how diversified style investing can potentially generate more attractive risk and return characteristics. AQR’s Style Premia Alternative Fund (QSPRX) and its Alternative Risk Premia Fund (QRPRX) both provide exposure to the carry trade and do so across asset classes. (Full disclosure: My firm, Buckingham Strategic Wealth, recommends AQR funds in constructing client portfolios.)

Summary

Baghdadabad and Mallik contribute to the large and growing body of evidence providing support for investors’ decision to include an allocation to the carry trade in their portfolios.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Here is a podcast with Dr. Roussanav. |

|---|

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.