Executive Summary

- Tax loss harvesting is widely promoted, but we think the benefits are generally misunderstood and often overstated.(1)

- The benefits of loss harvesting arise from tax deferral, similar to the benefits of saving in a retirement account.

- The benefits of tax deferral rise and fall with expected returns and the benefits are inversely related to future tax rates.

- Due to the wash sale rule, tracking error is a meaningful risk with loss harvesting strategies and can completely wipe out any benefit.

Introduction

Our goal as investment advisors is to help investors cut through the noise and complexity created by our industry. Tax loss harvesting is a popular strategy that we have become well versed in, and we believe that claims that tax-loss harvesting can add 1-2% of annualized return into eternity are grossly overstated.

In this thought piece, we show how tax loss harvesting works, and the realistic benefits one should expect. We start with a simple explanation of tax loss harvesting and its true benefit and then illustrate how changes in returns and tax rates might affect this benefit.

Loss harvesting is only about tax deferral, not avoiding taxes

Tax loss harvesting is a strategy intended to reduce one’s current tax bill by selling positions with losses, and buying them back in the future (after at least 30-days due to wash sale rules). Investors mistakenly believe the benefit of this strategy is the immediate tax savings. The taxes saved today will simply end up being paid in the future because proceeds from sales are reinvested into other assets, which will hopefully be sold at a profit and eventually taxed. Therefore any value add from loss harvesting comes from tax deferral, not permanent tax avoidance.

A simple example illustrates the value of tax deferral: let’s say you have $100 invested, but face a $20 tax bill, your net worth after-tax is $80. All else equal, you would rather push this tax payment out as far into the future as possible, so the full $100 could remain invested and continue earning a return. If you had a losing position that could be sold (and reinvested into something else) to offset the tax bill, this would allow you to keep the full $100 invested for longer. Therefore, you did not “save” $20, you simply allowed it to stay invested longer and grow more, until taxes end up paid at a later date.

We next measure how much this tax deferral is worth across various return and tax rate environments.(2)

How valuable is tax deferral? It depends on the environment

We can more easily study the benefits of loss harvesting by drawing an analogy. Retirement accounts like 401(k)s and IRAs give savers varying combinations of tax avoidance or deferral on contributions and returns. The ultimate benefit of these retirement schemes is contingent on the level of returns, as well as future tax rates.(3) Hence, these are the two factors we use to measure the benefits of tax loss harvesting. Of course, the length of the deferral also matters.

Impact of future returns

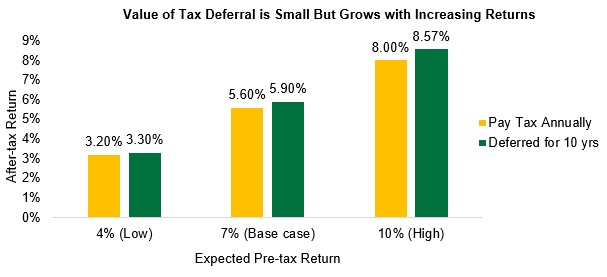

Let us assume the base case for returns is 7%, a reasonable assumption for equities looking forward. We also show the impact of a low return environment (assumed to be 4% annual return) versus a high return environment (10% annual return).

To understand the benefits of deferral, we compare a portfolio that pays taxes on its gains every year (at the 20% capital gains rate) versus deferring the tax payment until year 10. This means money compounds at 7% annually (in the base case), with a single, big tax hit in year 10. The charts below show the annualized, after-tax return of realizing gains and paying taxes annually versus deferring for 10 years in each different return environment.

As expected, the value of tax deferral rises and falls with expected return. And we can see that the benefits of deferral are small in every case, nothing like the 1-2% tax alpha promised by managers of loss harvesting strategies. These numbers are also in line with those in a study in the Financial Analyst Journal in 2003 which was based on Monte Carlo simulation, but did not account for transaction costs, which we have not yet either. These benefits from deferral are before accounting for any trading costs, which, as we will show later, often overwhelm these small advantages.

Impact of future tax rates

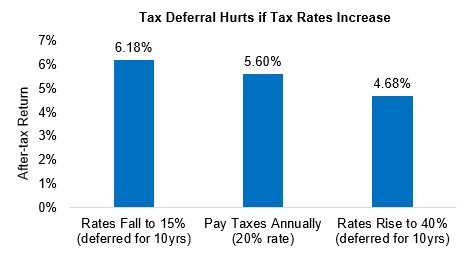

The second factor we consider is the level of future tax rates. We can do this in the same way as above, by comparing the returns of a portfolio paying taxes at current rates, versus higher or lower taxes in the future. Since capital gains rates are currently at 20%, we assume a low environment of 15% (the lowest level in the US since taxation began in the early 1900’s) and a high tax rate environment of 40% (the highest level for US capital gains taxes, hit in the early 1970’s), which is also comparable to the top income tax bracket today. The table below summarizes this comparison for a portfolio earning 7% per year.

With a tax deferred retirement account, value can be destroyed by deferring taxes if rates are significantly higher in the future. The same is true with tax loss harvesting. If one expects tax rates to rise in the future, then there is a benefit to paying taxes today and not deferring. Given the persistent and growing Federal budget deficits, at least here in the US, one could argue that such an environment of higher tax rates is probable.

The retirement account analogy is useful to understand benefits from tax deferral but it overstates the benefits of loss harvesting in at least two ways. Most importantly, a retirement account defers taxes on its entire value while loss harvesting does so only on the value of the loss. And related to this, loss harvesting involves trading costs on the full value of the position, not only on the value of the loss. We use the next section to illustrate just how small these benefits end up being after considering these additional points.

Where is the risk?

So far we’ve demonstrated the best case scenario for the benefits of tax loss harvesting, before real world costs and risks. The risks that further reduce its effectiveness are trading costs and that the substitute security does not closely track the one you want to hold.

We first look at the impact of trading costs.

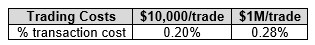

Trading costs present a hurdle rate for execution

Loss harvesting has easy to measure costs like commissions, bid-offer spreads, and market impact. Think of this as the minimum hurdle rate for implementing a tax loss trade. For small investors, commissions tend to dominate transaction costs, while for large investors, market impact is the bigger factor. Furthermore, keep in mind that loss harvesting involves at least 4 trades – a pair to sell your current holding and buy a replacement, and then a second pair of trades to unwind this. The table below summarizes the costs for small investors trading $10,000 at a time, versus larger investors trading $1,000,000 per trade. For the small investor, we assume a commission of $5/trade like what Schwab and Fidelity charge today. While for the larger investor we use Bloomberg’s transaction cost calculator to estimate market impact on US large cap equities for a series of 4 trades.

These estimates are based on only the most liquid positions in the Dow Jones index. With smaller, less liquid stocks, these costs will be meaningfully higher. These figures would also be significantly higher for less liquid international equities and most bonds.

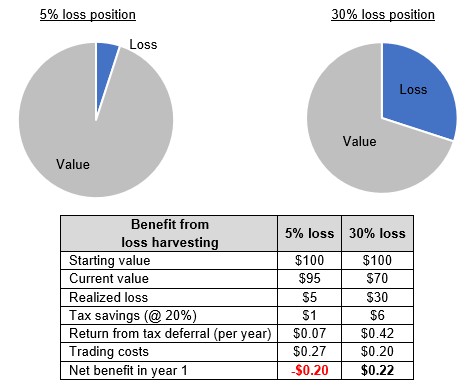

We show two examples to illustrate how trading costs can overwhelm potential tax benefits. The first, assumes we sell a position with a 5% loss and the second, with a 30% loss. Assume both positions were worth $100 to start. We also apply a 0.28% transaction cost to each case. Remember also that the benefit is only on the value of the tax deferred hence the small numbers. One can see that even with a 30% loss, net of costs, the benefit from harvesting this loss is only 0.17% of the starting portfolio value (assuming the same 7% expected return as the base case above). And this too ignores the final tax owed on the gains on the deferred tax. If loss harvesting trades are done too frequently, and on losses that are too small, the resulting portfolio churn will destroy value.

5% loss position 30% loss position

Trading costs help inform the threshold for undertaking tax loss harvesting but the benefits are still uncertain because future returns, tax rates, and amount of time until the final tax is owed are also unknown.

Tracking error risk

Another risk factor with tax loss harvesting is that US tax law prohibits you from purchasing a perfect substitute during the 30-day wash sale period. This introduces the risk of tracking error, because the performance of the replacement security you buy will differ from the security you are replacing. For example, one might temporarily sell Coca Cola shares and buy Pepsi, which have many similar characteristics but are not perfect substitutes.

Below are just two examples of how this risk can play out with a loss harvest trade:

- Relative Underperformance: Sell original position and buy a close substitute. But the substitute position underperforms your original holding while held. This relative loss may offset the tax deferral benefit.

- Taxable Short-Term Gains: If the substitute position delivers a positive return (whether it earns more or less than the original position is addressed above), the sale of it at the end of the 30-day wash sale window generates a short-term gain that will be taxed at higher income tax rates, rather than the long-term gains rate of 20%. This is effectively the same as lowering your cost basis (by realizing the loss) but then paying some of the future gains at a higher tax rate.

Given the known transaction costs, and volatility introduced by tracking error, we suggest using a Sharpe ratio framework to inform the threshold at which a loss is harvested. A high ratio of expected benefit to risk is desired and requires a position with a large loss, or one that reduces taxes charged at a high tax rate, and with a low tracking error to the substitute position.

How does the return benefit from loss harvesting compare to buy and hold investing?

How does loss harvesting compare to simple buy and hold investing when it comes to improving tax efficiency?

The drivers of tax efficiency are as follows:

- paying the lowest tax rate, and

- deferring taxes for as long as possible.

Historically, long-term capital gains taxes have been significantly lower than income tax rates. Simply buying and holding positions for at least a year is the most impactful way to improve tax efficiency. Currently the top income tax bracket is 37% federal plus state, local and other taxes like Medicare surplus, while long-term capital gains tax is only 20% plus similar other taxes. For the sake of this example, we assume the tax on short-term trading profits is 40% and 20% on long term holdings of over 1 year. We also have studied this in the context of the hurdle for active management outperformance in previous research.

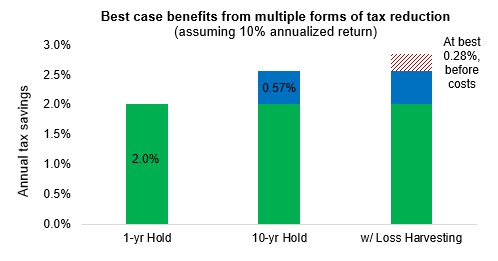

For a portfolio earning 10% per year (our high return environment), and doing so with short-term trading, one loses 40%, or 4% per year to taxes. Painful. If instead one could earn the same return by holding positions for one year and then selling, this cuts your tax bill in half, to 2% (20% of our 10% return). This is a huge boost to the bottom line.

The second benefit of buy and hold comes from deferring taxes for multiple years. This is the same source of benefit as tax loss harvesting, but without the trading costs. Deferring tax payments for a decade on a position growing at 10% per year improves after-tax returns by 0.57%. This is due to how compound interest works as we showed on page 2. Said another way, deferring taxes and letting your money compound lowers your effective realized tax rate.

We lastly estimate the benefit of loss harvesting as at best 0.28%, minus trading costs. This is half the 0.57% from deferral, because we assume one incurs a 50% loss so can defer gains equal to half their account value. For most investors this benefit will be close to zero as their losses will be smaller, returns likely lower, and there are always costs involved. The chart below summarizes the incremental benefit of each of these ways to lower taxes, alongside our optimistic loss harvesting estimate.

Note that the example above assumes a high return environment. As in our chart on page 2, the benefits of loss harvesting are likely wiped out by trading costs if future returns are 7% or lower.

Since loss harvesting is about deferral, it must be worse than buy and hold investing. Buy and hold benefits from tax deferral on the whole portfolio, while loss harvesting incurs trading costs and only benefits on the amount of any losses. Still, some might argue that they benefit from loss harvesting because other parts of their portfolio are frequently incurring short-term gains. In this case, the solution is not adding more complexity via tax loss harvesting, rather it is to fix the other part of the portfolio. It goes without saying that for loss harvesting to work, it must first be generating losses, certainly not the goal of anyone’s investment strategy.

Tax Loss Harvesting Rarely Adds Value

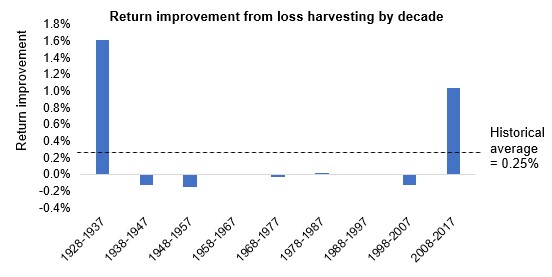

We next study a simple loss harvesting strategy on the S&P 500 going back to 1928, dividing history into 9 decades, to see whether the historical benefit is similar to what our logical framework suggests.

In each decade, we pick the optimal month to harvest losses (the lowest point for the index during each period) and then measure the additional return at the end of the period from harvesting the loss. In each case, when a loss is harvested, we assume that any tax savings are reinvested into our portfolio immediately. One month later (to comply with wash sale rule), the loss harvest trade is reversed, each with a 0.1% transaction cost. Short-term capital gains were taxed at 40% and long-term gains at 20% (also optimistic since historical tax rates for income and capital gains were higher for most of history).

The chart below summarizes the additional return for this loss harvesting strategy by decade. The two decades when loss harvesting generated a meaningful improvement (1928-1937 and 2008-2017), were decades with major financial crises and therefore large drawdowns for equities. Otherwise during most decades, there was negligible benefit from loss harvesting. There were even a few decades (1958-67 and 1988-97) where the index never dipped below its starting value and hence there were no opportunities to harvest losses.

We separately created a study that ignored the wash sale rule and assumed we could immediately reinvest back into the S&P 500 at the lowest point. Even here we found that the average benefit of loss harvesting was only 0.11% outside of the decades with financial crisis.

By using the S&P 500 index in this particular study, we can attempt to draw conclusions for a portfolio of multiple, diversifying (lowly correlated) securities. If we assume a portfolio of many uncorrelated positions (an aggressive assumption beyond a very small number of positions), then by extension, one should simply earn the ~0.25% benefit shown above more consistently than for a single position. There is optionality to harvesting losses at the individual position level, but this will not significantly raise the return benefit, only the consistency with which it is earned.

We have done a study with optimistic assumptions to put loss harvesting strategies in the best light but instead found almost no expected return benefits.

Conclusion

To harvest tax losses one must first lose money. And to harvest losses into eternity, one must be constantly losing money over long periods of time. Since markets rise over time, the benefits of loss harvesting should decline as time passes. We have shown that tax loss harvesting is a strategy with at best very small return benefits, that arise only from tax deferral.

We would avoid tax loss harvesting unless one of the following conditions applies to your portfolio:

Large losses at high tax rates (short-term losses): Large losses, especially those at high tax rates (short-term losses) are the most valuable when they are available to offset other realized gains.

Losing positions have low trading costs: Any trading activity incurs costs, tax loss harvesting is no exception. The trading costs of any position is the hurdle rate to determine whether to harvest a loss.

High expected returns: The benefits of tax deferral are higher when returns are high.

Lower expected future tax rate: Since loss harvesting is about tax deferral, not avoidance, it matters what final tax rate you pay. If your future tax rate will be higher, then it may be better to pay your taxes today.

Many who use loss harvesting as a strategy do so because they hold other tax inefficient investments. As we have shown, the tax efficiency improvements from loss harvesting are less than buy and hold investing. In which case, the solution is not to add complexity on top of complexity, but rather simplify your investment process.

One should always be aware of taxes in money management, but do not let the tax tail wag the dog. Selling a losing position that one no longer wants to hold is just common sense and good portfolio management. Selling an attractive long-term holding for short-term tax reasons generates costs and risks that tend to overwhelm the benefits.

References[+]

| ↑1 | a recent paper highlighted by Wes on twitter comes to a similar conclusion. Here is a discussion on the concept in the context of long/short investing by Larry Swedroe. Larry also pointed out that the cost/benefit analysis may be different in the context of other assets such as municipal bonds |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See here for a discussion in the context of the ETF wrapper. |

| ↑3 | See here and here for a post by Aaron Brask |

About the Author: Maneesh Shanbhag

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.