Risk and Investment Horizon: Is Time Really Money?

- Ekaterina E. Emm and Ruben C. Trevino

- Journal of Investing, 2019

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category

What are the Research Questions?

Typically, financial advisors prescribe a higher allocation to stocks for investors with long-term horizons but the effect of the length of the investment period on the risk of investment has long been debated in the finance literature.

The authors investigate the extent to which a risky investment can become safer given a longer holding period. Specifically, they ask the following research question:

- Is final wealth more at risk or less at risk as the holding period increases?

What are the Academic Insights?

By taking a two-step approach (MonteCarlo analysis + actual historic returns for US stocks, long term Bonds and T-Bills) over the period from 1926 and 2016, they find:

- The uncertainty of ending wealth increases with the holding period. In other words, the standard deviation of holding-period returns increases with the holding period. If the standard deviation was our only measure of risk, we would have to conclude that risk increases as the holding period increases.

- The probability of a loss decreases as the holding period increases. This is true for stocks, bonds, and T-bills. The probability of losing money over a five-year holding period, for instance, is lower than that of the one-year holding period. In this regard, extending the holding period reduces risk.

- More interestingly, the size of the worst possible loss initially increases, but after a few years, the size of the possible loss declines with the holding period. Investments, like stocks and bonds, become riskier at first but safer after a few initial years.

- Time diversification has more to do with a positive average return compounding through time than with good years canceling bad years.

- Although stocks have higher average returns than bonds, the probability that bonds will outperform stocks remains not trivial even for long holding periods. For example, in 22% of historical 10-year holding periods of bonds outperformed stocks. However, the probability of bonds beating stocks declines to only 7%, albeit still ample for a risk-averse investor, once the holding period becomes 20 years.

Why Does it Matter?

This study lends support to the practice of increasing the allocation to stocks in a portfolio if the investors have a long time horizon.

However, its results are based on a number of assumptions, that should be carefully kept in mind:

- The financial markets will continue to provide attractive average annual returns in the long run.

- Long-term investors can ignore intermediate short-term volatility. This is often not true.

- The goal of an investor is final wealth maximization. But in real life there are a number of other investment objectives and constraints.

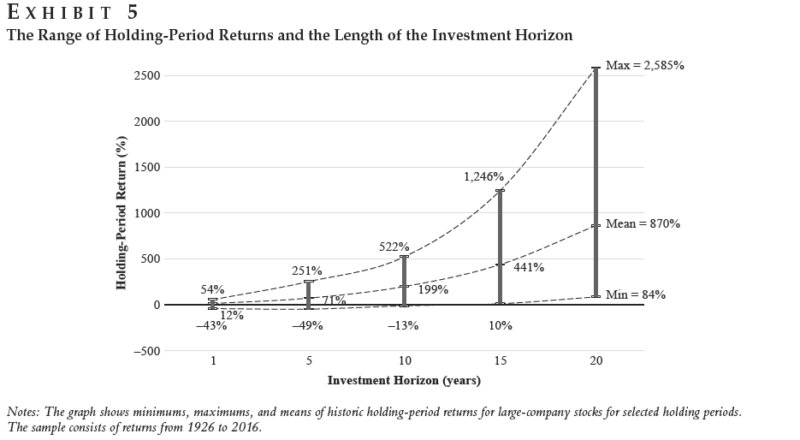

The Most Important Chart from the Paper

Exhibit 5 provides a clear graphical representation of the effect that the length of the holding period has on the minimum, the mean, and the maximum returns. The exhibit shows only the stock returns case. We can observe that the mean of total returns increases as the holding period increases. This is the result of the compounding process. Furthermore, the maximum of total returns increases at a faster rate. This is the effect of the distribution of total holding-period returns becoming lopsided. However, we can observe in the graph that the maximum loss (i.e., minimum of total returns) initially increases (gets worse) but after five years it starts to increase. For the one-year holding period the minimum return is -43% and gets worse for the five-year period, with a -49%. But by the 10-year holding period, the worst return is only -13.0%. No losses have occurred in stocks for a 15-year holding period. The worst possible return was 10%.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Abstract

In this study, we explore the extent to which a risky investment, like one in stocks, can become safer given a longer holding period. The key question is whether the final wealth is more at risk or less at risk as the holding period increases. We take a two-pronged approach: First, we use Monte Carlo simulation and perform a controlled analysis of the effect of the holding period on risk. Second, we examine the extent to which the actual historic returns are consistent with the simulation results. The sample period covers a total of 91 years, from 1926 to 2016. Our findings lend support to the common practice of investing more aggressively as the investment horizon lengthens.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.