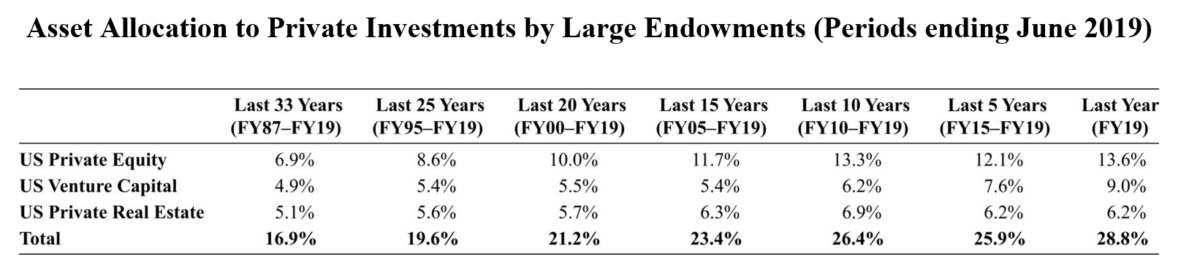

As the following table demonstrates, since its inception in the 1970s, the private equity industry has grown significantly. According to Preqin data, there are now more than 18,000 private equity funds, with assets under management exceeding $4 trillion.

When deciding on whether to allocate capital to private equity, investors should consider whether the investment can be replicated more efficiently with public equities by selecting stocks with characteristics similar to those of the buyout targets. Doing so would result in far lower diligence and monitoring costs, dramatically lower management fees, eliminate performance fees, offer daily liquidity, and provide much greater transparency.

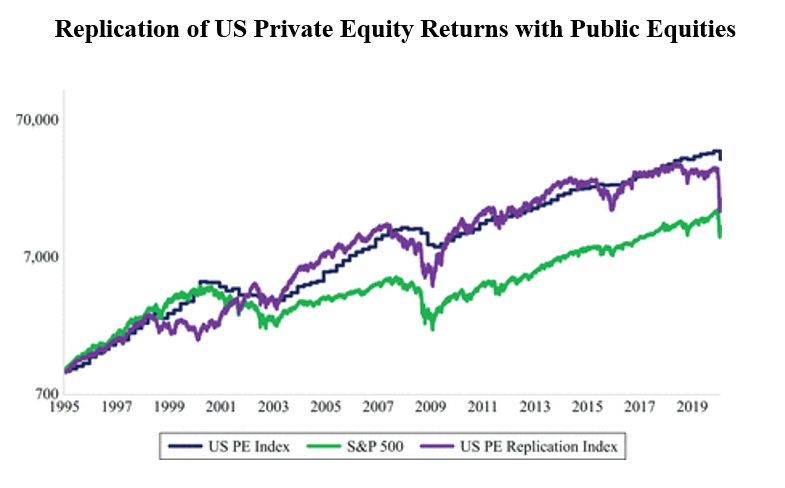

Nicolas Rabener contributes to the private equity literature with his study “Private Equity Is Still Equity, Nothing Special Here,” published in the December 2020 issue of The Journal of Investing. He analyzed the characteristics of U.S. private equity returns and presented an approach to systematically replicating these returns by using public equities. His universe was all stocks traded in the U.S. with a market capitalization larger than $500 million between 1995 and March 2020. For stock selection, he used a sequential model that first selected the 30 percent of stocks that represented the smallest companies, then the 30 percent of those that were the cheapest, and finally the 30 percent of stocks that represented the most levered firms within that sample of small and cheap stocks. A firm’s size was proxied by market capitalization, valuation based on an equal-weighted combination of price-to-book and price-to-earnings multiples, and leverage with the debt-over-equity ratio. The resulting portfolio was concentrated and comprised small, cheap, and highly levered stocks, which were weighted equally and rebalanced monthly.

The private equity returns were sourced from Cambridge Associates, an investment consultancy, which aggregated the net returns of more than 1,400 U.S. private equity funds between 1995 and March 2020. Rabener cautioned that, as Cambridge pointed out in their 2020 report, private equity returns were likely overstated as a result of survivorship bias because the reporting was voluntary and because poorly performing funds typically stopped reporting their returns. In addition, endowments that employ internal staff members to analyze private equity opportunities do not net this expense from the returns they report to the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO). The magnitude of this performance overstatement is not trivial. Some large endowments reportedly incur annual internal management fees of 50 basis points or more.

Rabener also added this caution about reported private equity internal rate of return (IRR) calculations:

The strategy of measuring returns as IRRs can be questioned because the private equity industry has devised innovative tricks to generate high IRRs that might seem appealing to capital allocators in marketing materials but ultimately equate to less attractive money multiples over the life of a fund. For example, a common practice is forcing acquired companies to pay a dividend to the private equity fund immediately after acquisition, which boosts the IRR because of the money-weighted calculation. However, the IRR methodology assumes a reinvestment of interim cash flows at equivalent returns, which is largely unrealistic.

For example, a private equity (PE) fund reports a 50 percent IRR and has returned cash early in its life. The IRR assumes the cash was put to work again at a 50 percent annual return. In reality, investors are unlikely to find such an investment opportunity every time cash is distributed. With that understanding, Rabener did use (abuse) the reported IRRs as time-weighted returns simply for lack of better alternatives.

Rabener began with the following chart, which helps explain the popularity of private equity given its significantly higher returns compared to the S&P 500 over the last 25 years. However, he noted:

“The trends in performance in US private equity and US equities are largely the same during that period. We observe that stocks seem to be leading private equity, which is explained by listed securities that are valued daily compared to quarterly or less frequently for the holdings of private equity funds.”

Following is a summary of his findings:

- U.S. private equity returns can be replicated systematically through public equities, historically by selecting small, cheap, and levered stocks.

- Investing in private equity entails the same economic exposure as investing in public equities, resulting in the high correlation of both asset classes. For example, using quarterly reporting, the correlation of returns of private equity and the S&P 500 was almost 0.8—adjusting for smoothing of private equity returns would result in an even higher correlation.

- The volatility of private equity returns is understated as a result of smoothing, and the risk-adjusted returns are comparable to those of public equities. An unsmoothing approach results in comparable standard deviations of returns for private equity and the S&P 500.

- There are not many sound arguments for private equity firms to avoid using public market multiples to measure the changes in the valuations of portfolio companies and provide daily returns to their investors. Doing so, however, would make private equity look much more like public equities and seem far less unique from a capital allocation perspective.

- While most private equity firms highlight the value, they create by improving the operations of acquired firms, these efforts do not translate into consistent outperformance compared to public equities.

Rabiner also examined the differences in leverage and its impact on risk.

The Role of Leverage

Privately held companies carried three times the leverage of stocks included in the S&P 500 and almost 50 percent more leverage than the small, cheap, and levered stocks that constitute the U.S. PE Replication Index—the greater leverage should be considered when measuring risk-adjusted returns. Given such high leverage, the default rates of private equity holding companies are higher than those of publicly listed companies. For example, the 2019 study “Leveraged Buyouts and Financial Distress” found a 20 percent bankruptcy rate within 10 years based on a sample of 467 U.S.-based listed companies that were taken private by buyout firms from 1980 to 2006 compared to 2 percent for a control group.

Changing Nature of Private Equity

Rabener also noted that the characteristics of the buyout targets have become more diverse over time, and the targets are no longer mostly small companies because the economics for private equity firms are enhanced when focusing on larger targets:

“Small and cheap companies require only a minor equity investment, but a significant amount of management time and resources are necessitated to improve operations. In contrast, investing in large and growing companies allows private equity firms to deploy more equity, generating more fees to the private equity firms and demanding less time and resources for managerial overhauls.”

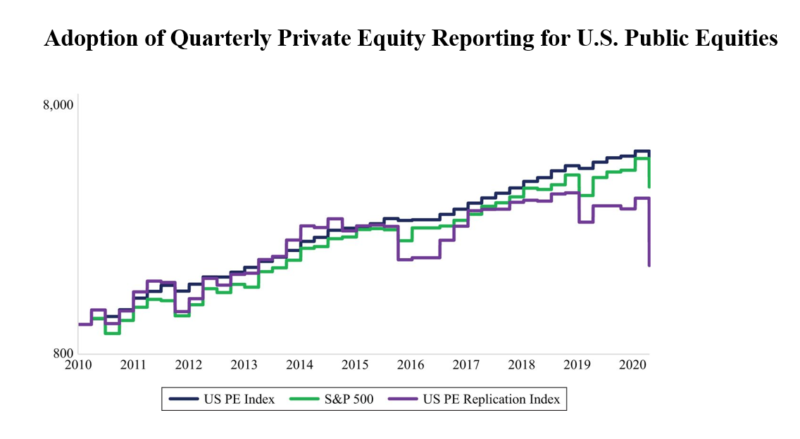

The following chart, which adopts the private equity standard of quarterly reporting for public equities, covers the last 10 years and shows how the performance of private equity has been highly correlated with that of the S&P 500. He added that, in contrast, over this period:

“small, cheap, and levered stocks have underperformed since 2015. Some analysts compare this period to the technology bubble in 2000 as investors express a strong preference for growth stocks over value stocks in recent years. The poor performance of the US PE Replication Index is especially pronounced during the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 as investors became increasingly concerned that small, cheap, and levered companies would perform less well during a global pandemic than larger ones.”

His findings led Rabener to conclude that the attributes of private equity:

“in addition to the complexity and illiquidity of the asset class, make private equity unattractive compared to public equities and challenge its current popularity among capital allocators.”

He concluded that:

“The private equity industry is largely a mirage built on a lack of transparency and that private equity provides less value for capital allocators than previously thought.”

Summary

Rabener’s findings on risk-adjusted returns are consistent with those of the 2013 study “Limited Partner Performance and the Maturing of the Private Equity Industry,” the 2017 study “Replicating Private Equity with Value Investing, Homemade Leverage, and Hold-to-Maturity Accounting,” and the 2018 study “The Grand Experiment: The State and Municipal Pension Fund Diversification into Alternative Assets.”

More bad news comes from the authors of the 2017 paper “How Persistent Is Private Equity Performance? Evidence from Deal-Level Data,” who concluded:

“Overall, the evidence we present suggests that performance persistence has largely disappeared as the PE market has matured and become more competitive.”

The authors added:

“Those Limited Partners (LPs) who were early investors in PE – such as endowments – established relationships with successful GPs which were valuable when the market was developing. However, those relationships, and access to funds – at least on the buyout side – are now much less valuable and are no longer a source of LP out-performance.”

While some private equity firms are willing to acknowledge that industry returns on average fare no better than public equities, they point out that the best-performing buyout funds continue to outperform the S&P 500. Unfortunately, for most investors this argument is basically irrelevant, as only a few can invest in the best-performing funds. Most investors, certainly most individual investors, will earn average returns, which are not attractive considering the illiquidity of the asset class.

Furthermore, only limited evidence documents consistency in the performance of private equity firms. For example, the authors of the 2020 study “Has Persistence Persisted in Private Equity? Evidence from Buyout and Venture Capital Funds” found that while there is evidence of persistence for venture capital (VC) funds when using information available at the time of fundraising—top quartiles tended to repeat nearly 45 percent of the time—the evidence was much weaker for buyouts when using information available at the time of fundraising. While performance persistence existed prior to 2000, the evidence has become much weaker since. And the case against persistence has deteriorated considering the dramatic increase in capital inflows in recent years.

Note that the research, including the 2020 study “The Persistent Effect of Initial Success: Evidence from Venture Capital,” has found that initial success does matter for the long-run success of VC firms but that these differences attenuate over time and converge to a long-run average across all VC firms. Initial success matters because it becomes self-reinforcing as entrepreneurs and others interpret early success as evidence of differences in quality, giving successful VC firms preferential access to and terms in investments. This fact may help to explain why persistence has been documented in private equity but not among mutual funds or hedge funds, as firms investing in public debt and equities need not compete for access to deals. It may also explain why persistence among buyout funds has declined as that niche has become more crowded.

Important Disclosure:

This article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. The analysis contained in the article is based on third-party information and can become outdated or otherwise superseded at any time without notice. Third-party information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements, or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability, or privacy policies of these sites and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products, or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Wealth Partners, collectively Buckingham Strategic Wealth® and Buckingham Strategic Partners® R-20-1605

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.