My August 17, 2020, article for Advisor Perspectives, “Factor-Based Investing Beats Active Management for Bonds,” provided the evidence from a series of academic papers on the ability of common factors to explain the variation of returns of bond funds, results which have important implications for investors in terms of portfolio construction, risk monitoring and manager selection. Following is a summary of the findings:

Following is a summary of the findings:

- Because the term, default and prepayment factors explain almost all the returns of bond portfolios, investors should construct them with these factors in mind and then carefully monitor their exposure to these systematic risks.

- Because the findings show little evidence of persistent ability to generate alpha beyond the randomly expected, investors should choose their fixed-income managers based mainly on expense ratios and exposure to term risk (the default premium was not only well explained by market beta, but it has also been very small, even before costs).

- Because factor betas drive compensated return and risk in bonds, it is far more important to capture desired factor betas efficiently than to seek alpha.

These findings demonstrate that the value premium has been pervasive, not only across global equities but across the fixed-income asset class as well. For example, the study “Value and Momentum Everywhere” found value premiums in both currencies (the well-documented carry trade) and commodities(1). Such findings minimize the risk that the historical value premium is a result of a data-mining exercise.

Söhnke M. Bartram, Mark Grinblatt, and Yoshio Nozawa contribute to the bond investing literature with their August 2020 study “Book-to-Market, Mispricing, and the Cross-Section of Corporate Bond Returns.” The traditional finance view of book-to-market (BtM) is that all else equal, high-risk firms discount future cash flows at higher rates, implying that high-risk firms have both low market prices and high book-to-market ratios—the greater risk generates a value premium. Behavioralists argue that the value premium is a result of mispricing. With evidence on both sides, perhaps the premium results are partly explained by both risk and mispricing. Yet the evidence, as presented in the annual SPIVA Scorecards, demonstrates that the large majority of active value managers persistently underperform their benchmarks and that there is no evidence of persistence of performance beyond the randomly expected.

The authors began by noting:

“Unlike equities, bond maturities tend to be finite, and bond cash flow streams are not only contractual but also of shorter duration than equity streams. These factors make the magnitude and timing of bonds’ future cash flows more transparent than those of equities. Indeed, the future cash flows of many bonds are known with relative certainty, as it is only the more extreme and relatively infrequent outcomes for the economy or a company’s prospects that affect the likelihood of the bonds’ promised payments being made.”

They defined the “bond book-to-market ratio” (BBM) as the bond’s book (or carrying) value per unit of face amount divided by the bond’s market price per unit of the face amount. At the time a bond is issued, and in the vast majority of cases, coupons are set so that the BBM ratio starts at close to one (a par bond).

Their data sample spanned the period January 2003 to April 2018 for trading signals and from February 2003 to September 2020 for bond returns which covered 8,925 different bonds and 838 firms.

Following is a summary of their findings:

- Controlling for numerous risk factors tied to default and priced asset risk, including yield to maturity, the ratio of a corporate bond’s book value to its market price strongly predicts the bond’s future return.

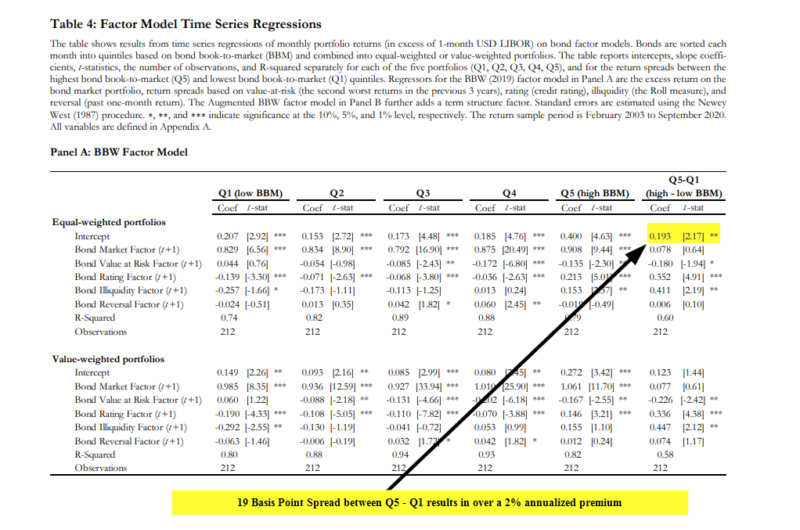

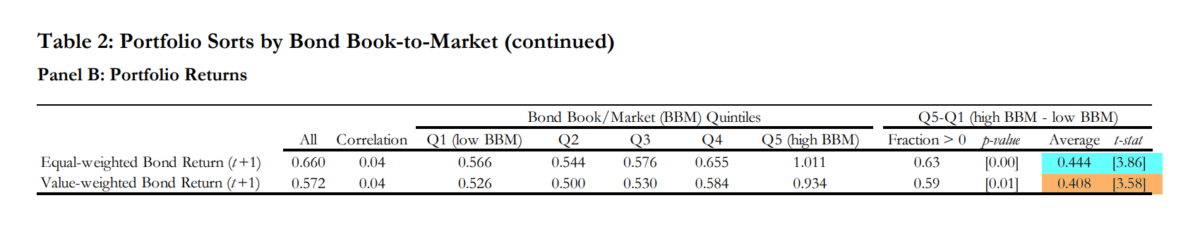

- The quintile of bonds with the highest bond book-to-market ratios outperformed the quintile with the lowest ratios by more than 2% per year, other things equal. Most of the alpha came from the long leg.

- The average monthly spread between the returns in the largest and smallest BBM quintile was 44 basis points (bps) per month when equal-weighted and 40 bps per month when value-weighted (both statistically significant), and the fraction of months in which the Q5-Q1 return spread was positive was 63% equal-weighted and 59% value-weighted (both statistically significant).

- High BBM bonds tend to have poorer credit ratings and are closer to default. They also have higher bid-offer spreads.

- The BBM anomaly is stronger for the more comprehensive bond universe that includes junior and puttable bonds.

- For the 20% of bonds that were closest to default, the BBM signal had about the same efficacy as it did for the remaining 80%—casting doubt on the risk-based explanation.

- The efficacy of the BBM signal for corporate bonds decayed rapidly as the signal became stale, making strategies with lower turnover and lower transaction costs, like buy-and-hold for one year, as unprofitable (net of trading costs) as their higher turnover counterparts. The rapid decay is also more suggestive of mispricing rather than risk mismeasurement as the source of the anomaly.

- About two-thirds of mispriced bonds returned to their fair values on a staggered schedule within the first three months of extreme BBM classification, and almost all bonds converged to their fair values over four to seven months.

- On average, the bonds in Q5 traded 209 times in months t + 1 and t + 2, whereas those in Quintile 1 traded on average 84 times.

Their findings led Bartram, Grinblatt, and Nozawa to conclude:

“Given that the future cash flows of corporate bonds, particularly senior bonds, are far less risky than their equity counterparts, bond price movements have to arise largely from discount rate variation rather than from changes in projections of future cash flows. Thus, our key finding—that a book-to-market signal for bonds generates risk-adjusted bond alphas that are almost as large as the alphas book-to-market generates in equity markets—favors mispricing over risk mismeasurement as the better explanation of the book-to-market phenomenon.”

They added the caution that transaction costs play an important role because the market for corporate bond returns is relatively thin, much less so than for equities:

“The risk-adjusted profits from the monthly-rebalanced BBM signal do not survive transaction costs, which are substantially higher in the corporate bond market than in the stock market. These transaction costs remain an obstacle for hedge funds and other short-term arbitrageurs. … Nevertheless, a buy-and-hold variation of the strategy does survive the transaction costs incurred by larger transaction sizes, enhancing overall net performance provided the institutions avoid additional short sales costs and constraints, for instance by tilting a long-only portfolio towards underpriced and away from overpriced bonds to some degree.”

Important Disclosure:

The content of this article of informational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information may be based upon third party data which may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Third party information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of the Buckingham Strategic Wealth® or Buckingham Strategic Partners®, collectively Buckingham Wealth Partners. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, confirmed the accuracy, or determined the adequacy of this article.

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.