We were recently asked what we thought about bonds as an investment. A lot of this was inspired by my comments on bonds via a discussion on how I personally invest. I’ll repost what I said on bonds below:

What are your thoughts on bonds and commodities?

In general, I’m not a fan of corporate bonds as a buy-and-hold asset class. Outside of treasury bonds, most bonds earn lower returns than equity, but they act a lot like equity when the world is on fire. And to make matters worse, most of the appreciation is tied to income, which has a terrible tax burden. Could I be convinced in certain situations to invest in non-treasury bond assets? Sure, but I’m not a fan, overall.

But let’s talk Treasuries. US Treasury bonds are unique because they still sit in the coveted “flight to safety” asset class (at least, historically, when inflation expectations aren’t high). On their own, treasury bonds are terrible investments, but IF one is convinced they can provide insurance against chaos in your stock portfolio, they can be an incredible diversifier. Fortunately, we’ve looked into the “crisis alpha” aspect of bonds, and the story is mixed. A lot of the insurance benefits tied to treasury bonds are related to high underlying coupons. But if the high coupon rates are gone, you aren’t left with much. Not to mention that the key reason Treasury bonds act like insurance assets is due to their unique position as a safe-haven asset. If their status as the liquidity/safety king becomes questionable, their investment merit becomes extremely questionable.

Where does that leave us with bonds?

Well, when in doubt, trend-follow. I can’t predict what treasury bonds will do, but I am a fan of trend-following longer-duration Treasury bond exposures — if they are in a positive trend, own them; otherwise, own cash and cash equivalents. And that’s what I do in my own portfolio. Part of our managed futures strategy is investing either long or short in the various government 10-year and 30-year duration bonds around the globe. But I have a 0% allocation to static buy and hold bonds. That’s crazy, IMHO.

How about commodities? Same as above. No buy and hold — trend-follow only.

As described, I am personally not a fan of a buy-and-hold allocation to long-duration bonds (i.e., bonds that have a strong sensitivity to interest rates because the cash flows are long-dated). In fact, I’m not a fan of buy-and-hold for any ‘diversifier’ asset that is organically low-return and has poor tax efficiency (bonds, commodities, crypto, etc).

What follows below is an empirical analysis of my preference for trend-followed bond exposures.

Over the Long-Haul, How do B&H TBonds and Trend TBonds Compare?

For this analysis, I lean on our internal return database, which has standardized total returns for a variety of asset classes going back to 1927.(1)

The specific return streams we’ll examine are as follows:

- Trend TBond = B&H TBond but with trend-following applied.

- B&H TBond =A spliced series of intermediate-term bond indexes from 1982+, and long-term bond indexes prior to 1982.

- RF = Spliced treasury bill indexes.

To generate the Trend TBond return, we deploy several long-term trend following rules on each of these asset classes from 1927 to June 2022.(2)

The chart below is a visual comparison of the different strategies:

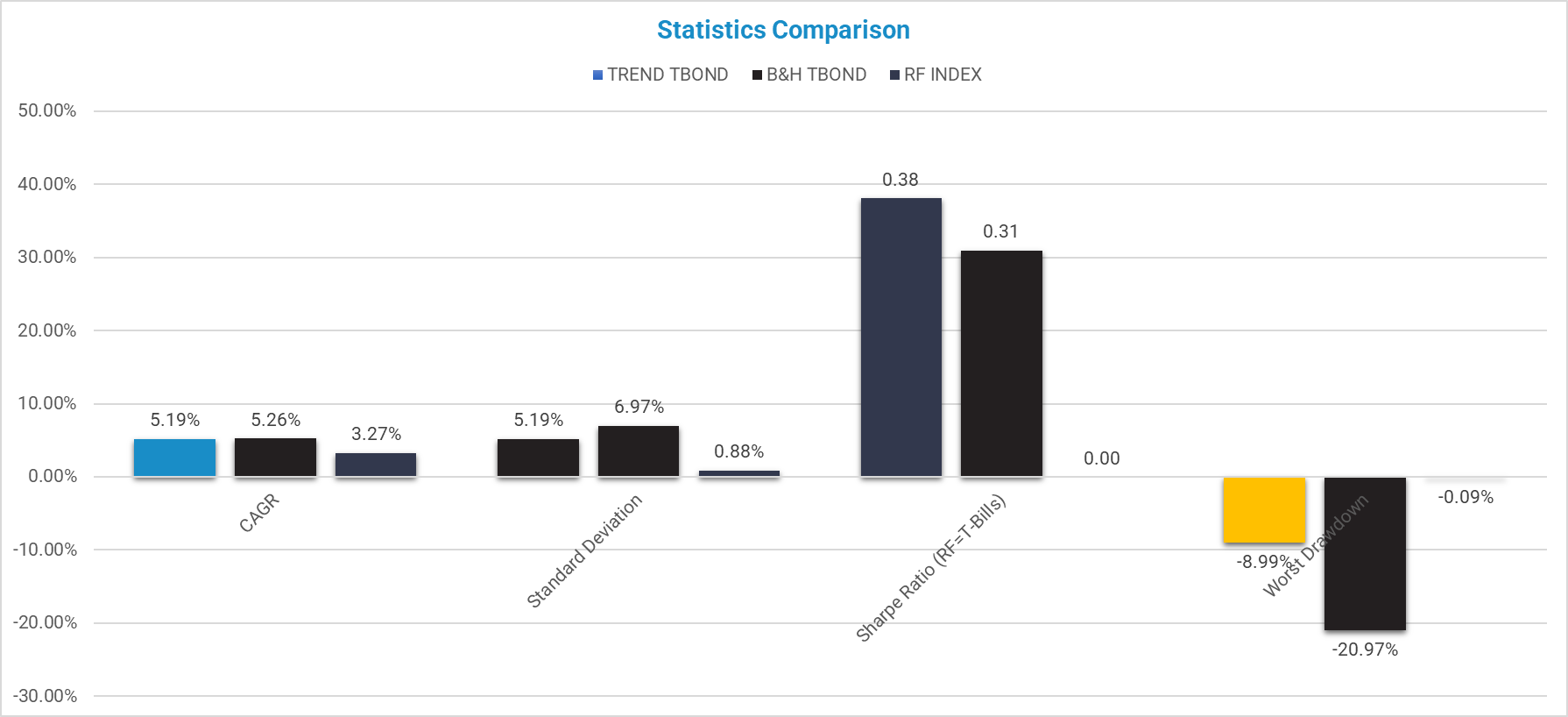

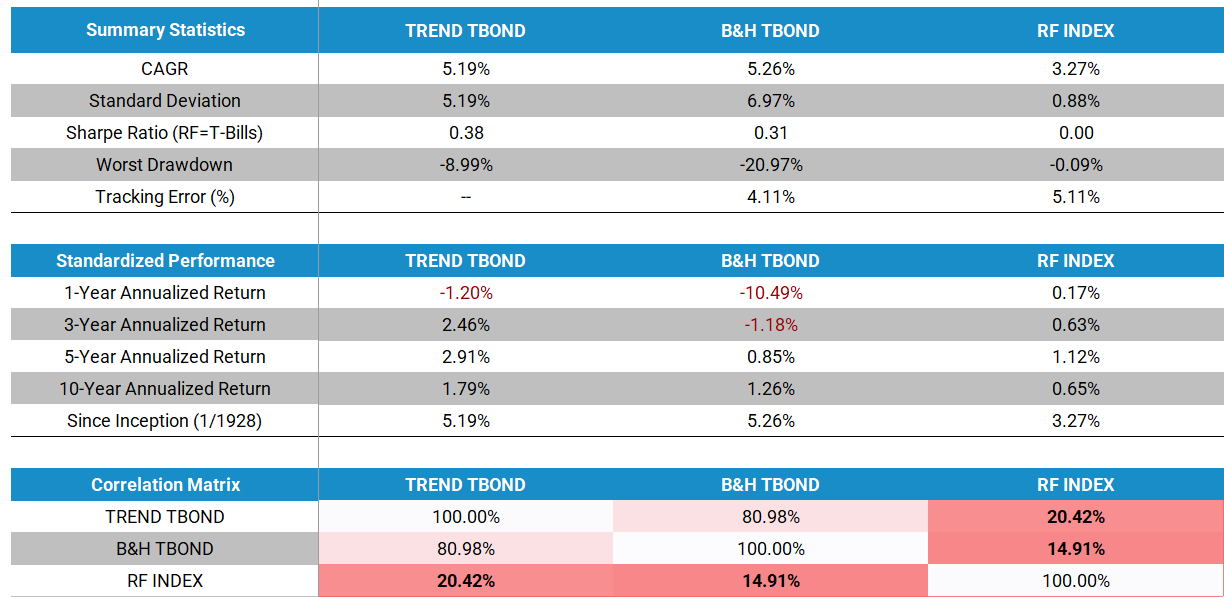

The trend followed Treasury Bonds are clearly favorable to the buy and hold equivalent in this sample period, with similar returns, but a much better risk profile.

Here are some more details:

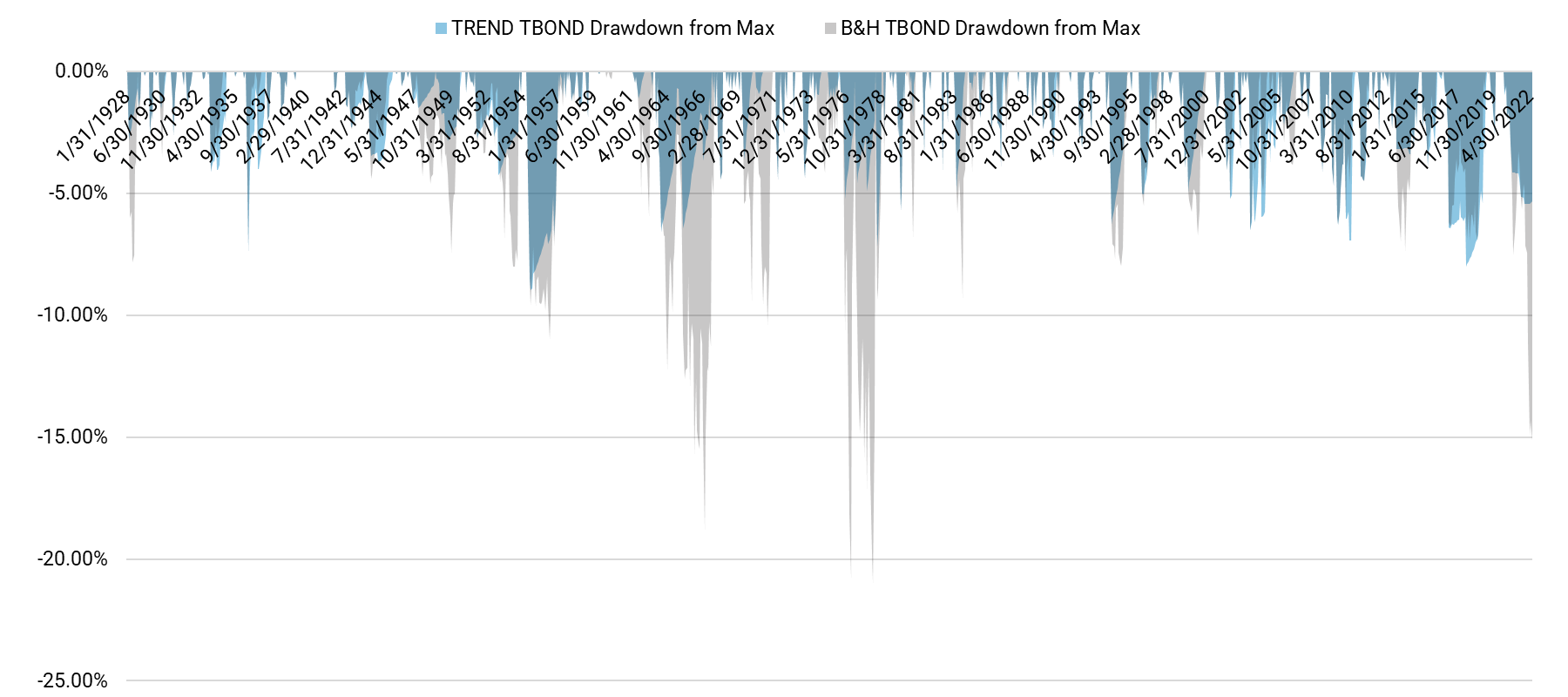

Next, we have the drawdown profile over time:

Conclusion? B&H sucks compared to trend-followed bonds.

But how does this look in a portfolio context?

Looking at the results on a single asset class can be misleading, or a red herring, because the results may not capture how an asset class works in a portfolio context. The simplest example might be an asset class that acts like insurance — ie loses most of the time, but wins when the world blows up (e.g, trend-based mgd futures). On a stand-alone basis, this asset looks terrible, but when combined with an equity portfolio, it might look pretty good. You can also have the opposite situation, a stand-alone asset might look awesome (e.g., let’s add US private equity exposure alongside our US public equity portfolio), but because it is so correlated with other stuff in your portfolio, it adds little value — and might even detract value after fees/taxes/brain damage! Regardless, the main point is that reviewing how an asset acts within a portfolio is often more important than looking at an asset class on a stand-alone basis.

Below we conduct the following simple experiment and the specific return streams we’ll examine are as follows:

- 60/40 w/ Trend TBonds = 60% US Stock Market; 40% Trend TBonds

- 60/40 w/ B&H TBonds = 60% US Stock Market; 40% B&H TBonds

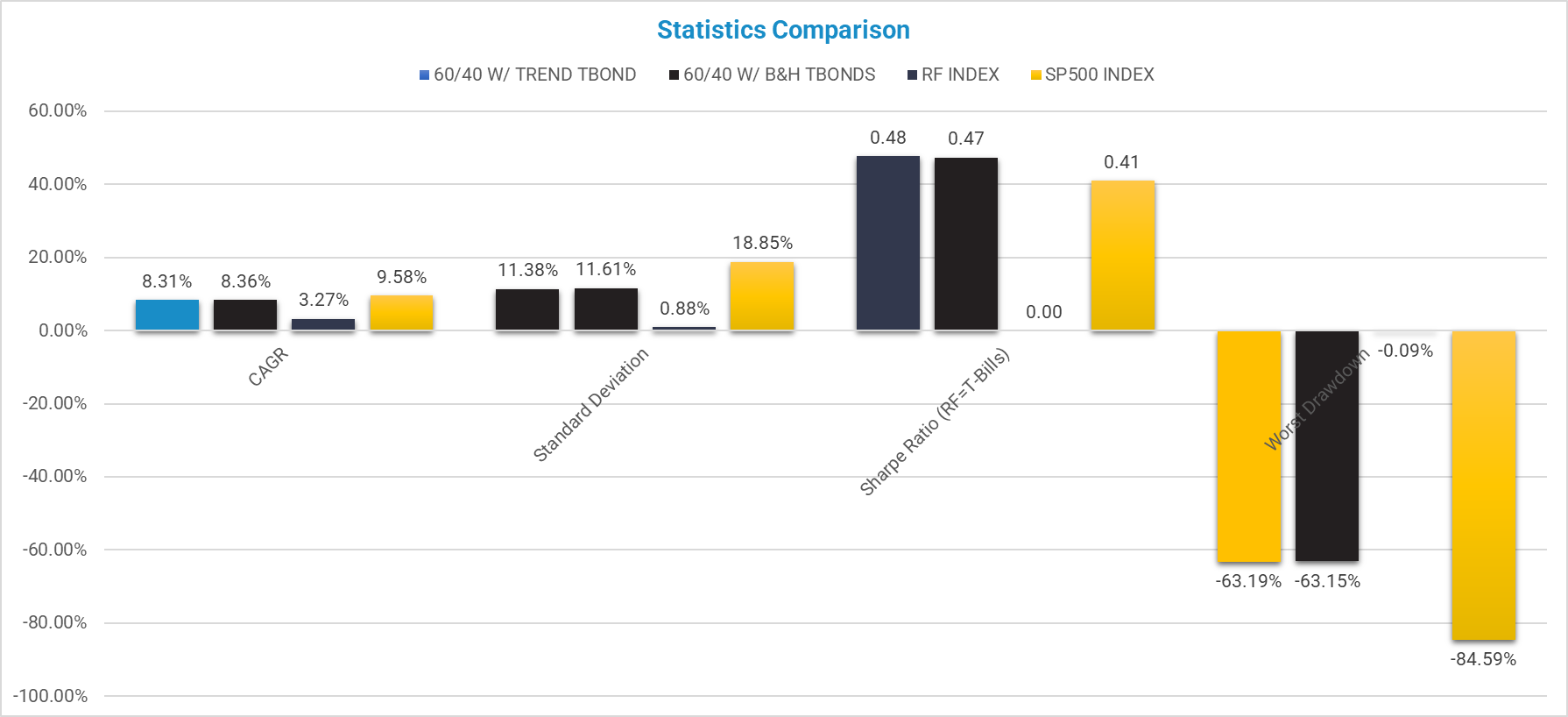

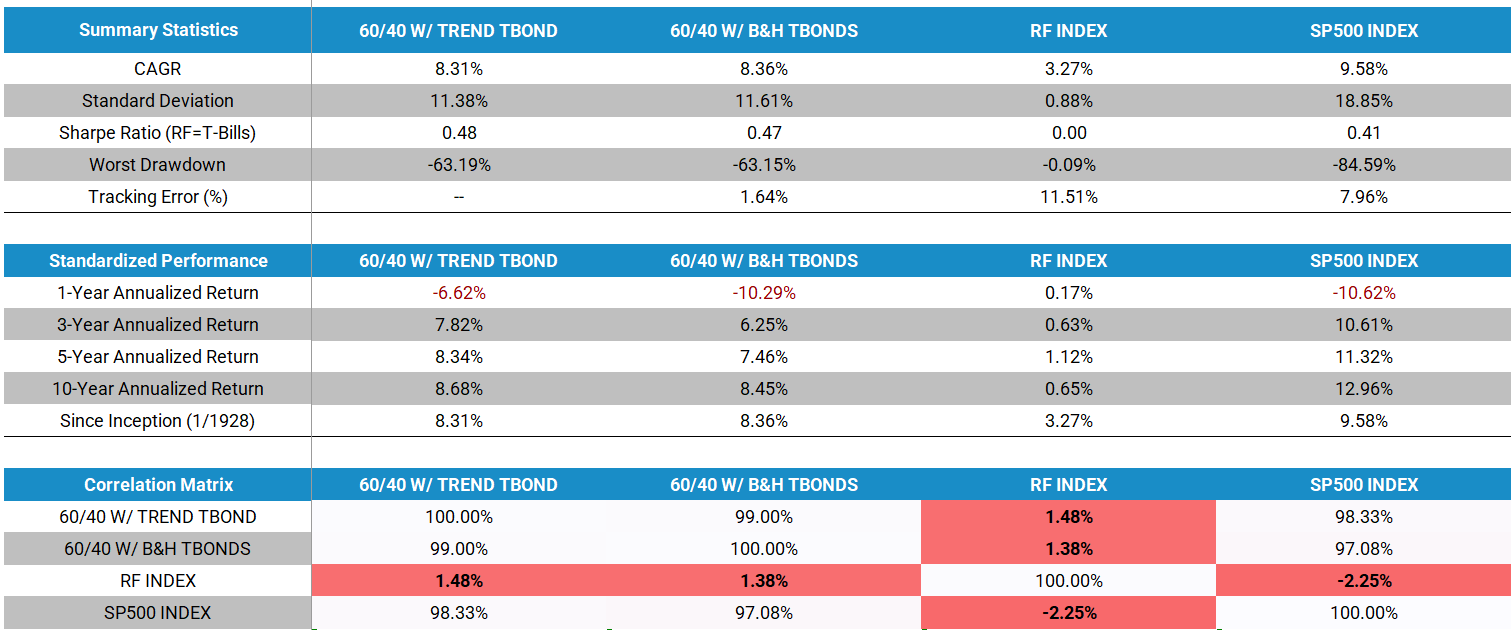

First, a look at the basic portfolio stats:

Not really much of a difference. Clearly, the equity exposure is driving a large portion of the action and any differences in B&H and trend-followed bonds are mostly irrelevant in the grand scheme.

Here are the more detailed stats and the numbers:

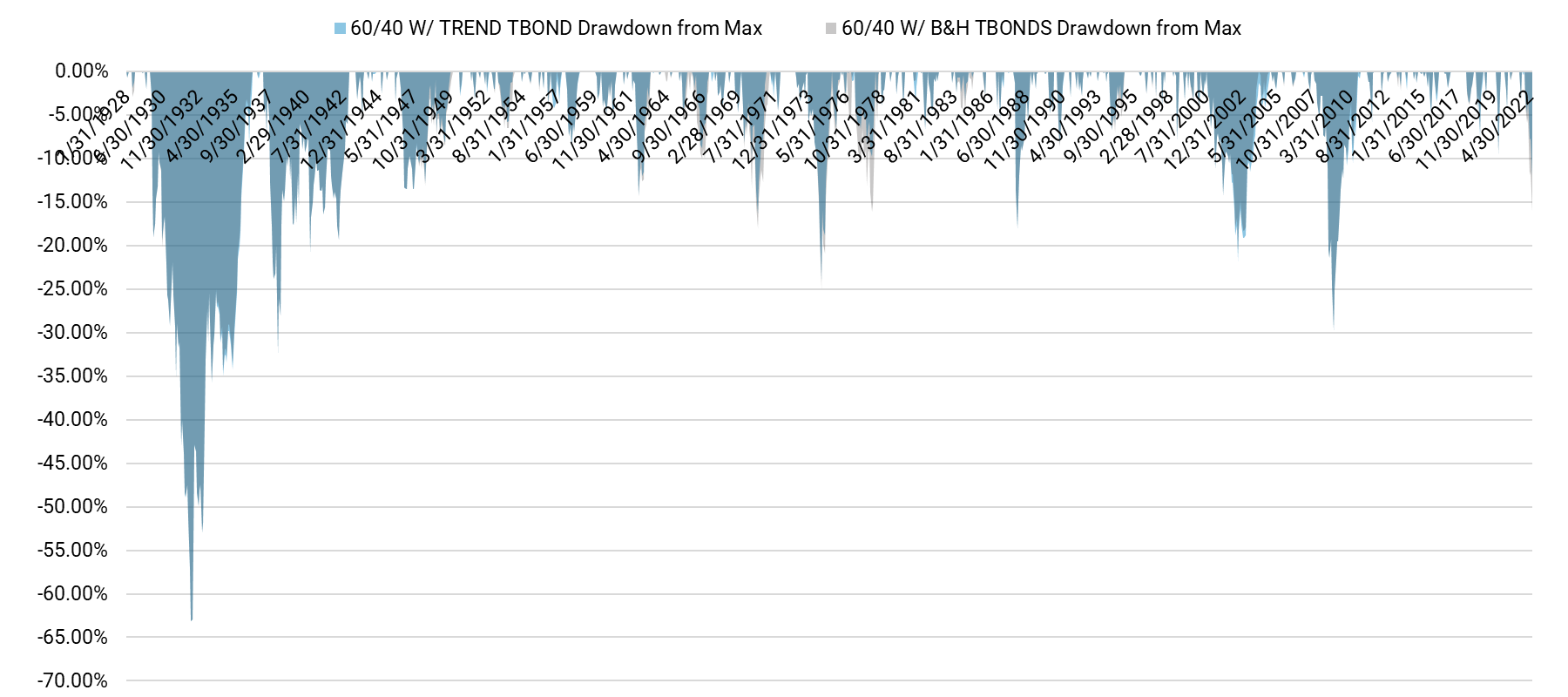

Finally, here is the drawdown chart over time:

Outside of some episodes in the ’70s and in the recent past, not much of a difference!

Conclusions

The analysis above is meant to be simple and easy to replicate. One can certainly engage in intense data-mining efforts, examine different sample periods, layer on piles of trend-following complexity, and so forth. But I’m not a fan of overcomplicating things in a complicated world — who needs the brain damage?

Bottom line: In a broader portfolio context, the analysis suggests that how one ‘eats’ their bond exposure, either via trend-following or buy-and-hold, is largely irrelevant because the portfolio’s long-term outcome will be driven by equity market dynamics. Bonds systematically lower an equity-centric portfolio’s returns, but they also lower the risk profile of the overall portfolio.

Good luck!

References[+]

| ↑1 | We have data that goes back further but it’s a lot more work to splice things together. You’ll have to excuse my laziness. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The figure below outlines the trend-following approach, visually.

The details of the rules are as follows: 1. Time Series Momentum Rule (TMOM) This rule is meant to avoid assets with poor absolute performance.

2. Simple Moving Average Rule (MA) This rule is meant to avoid assets with poor trending performance.

TMOM and MA rules are highly correlated but there are circumstances where the rules have a difference of opinion. |

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.