Many factor investors are familiar with “small-cap value investing,” which is a reasonable allocation for long-term investors who can tolerate a lot of volatility.

Why are there so many small-cap value investors?

Small-cap value investors have been told that the value premium is higher, on average, in small stocks versus larger stocks. Unfortunately, this is not true if you are a long-only value investor.(1). Our own Jack Vogel recently published a paper called “Long-Only Value Investing: Does Size Matter?” which makes this point clear.(2)

The fact large-cap value and small-cap value stocks earn similar returns may be shocking for investors who have been sold the idea that value investors have to invest in small-caps to capture the value premium. But we need to remember that data/evidence should drive decisions, not stories.

A simple example will highlight the fragility of the result that small-cap value beats large-cap value.

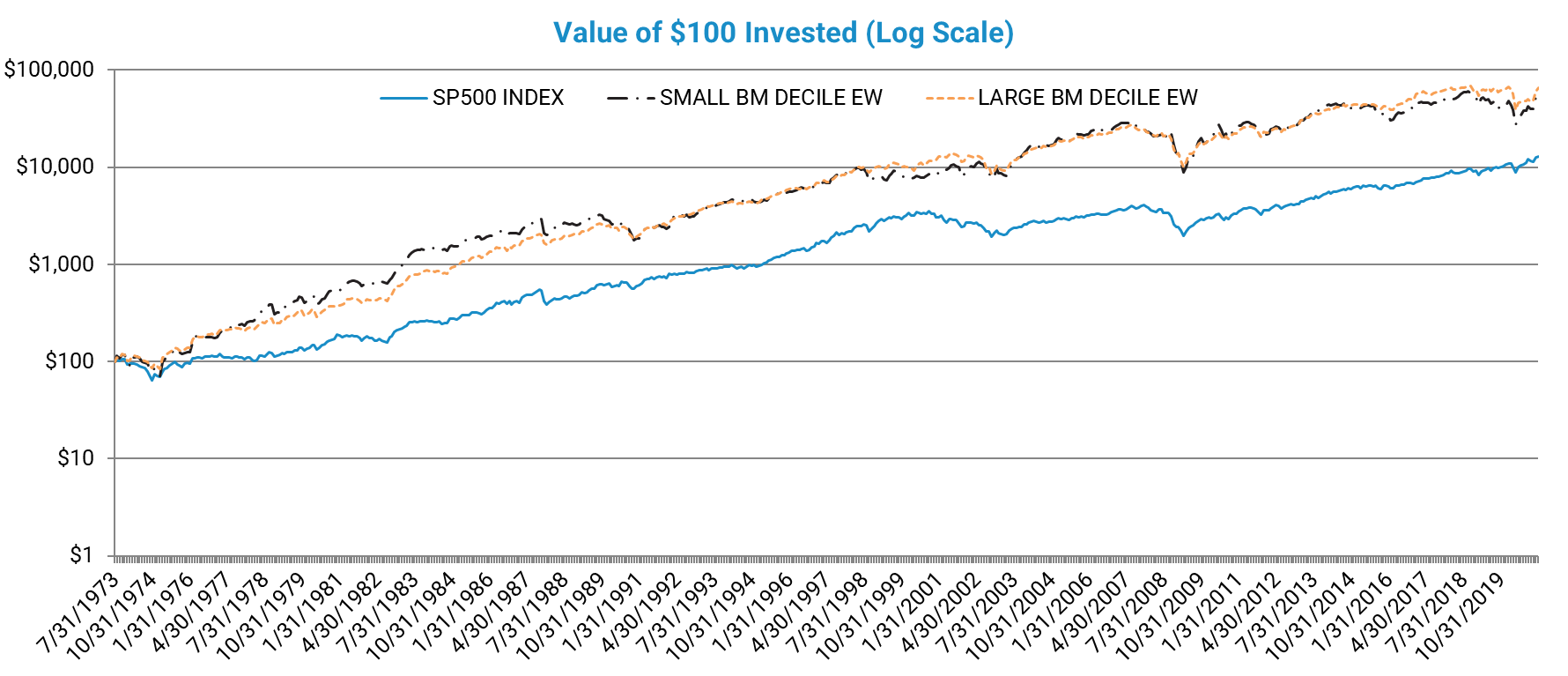

First, let’s look at a chart of equal-weight long-only portfolios sorted on book/market via the data from the paper.(3)

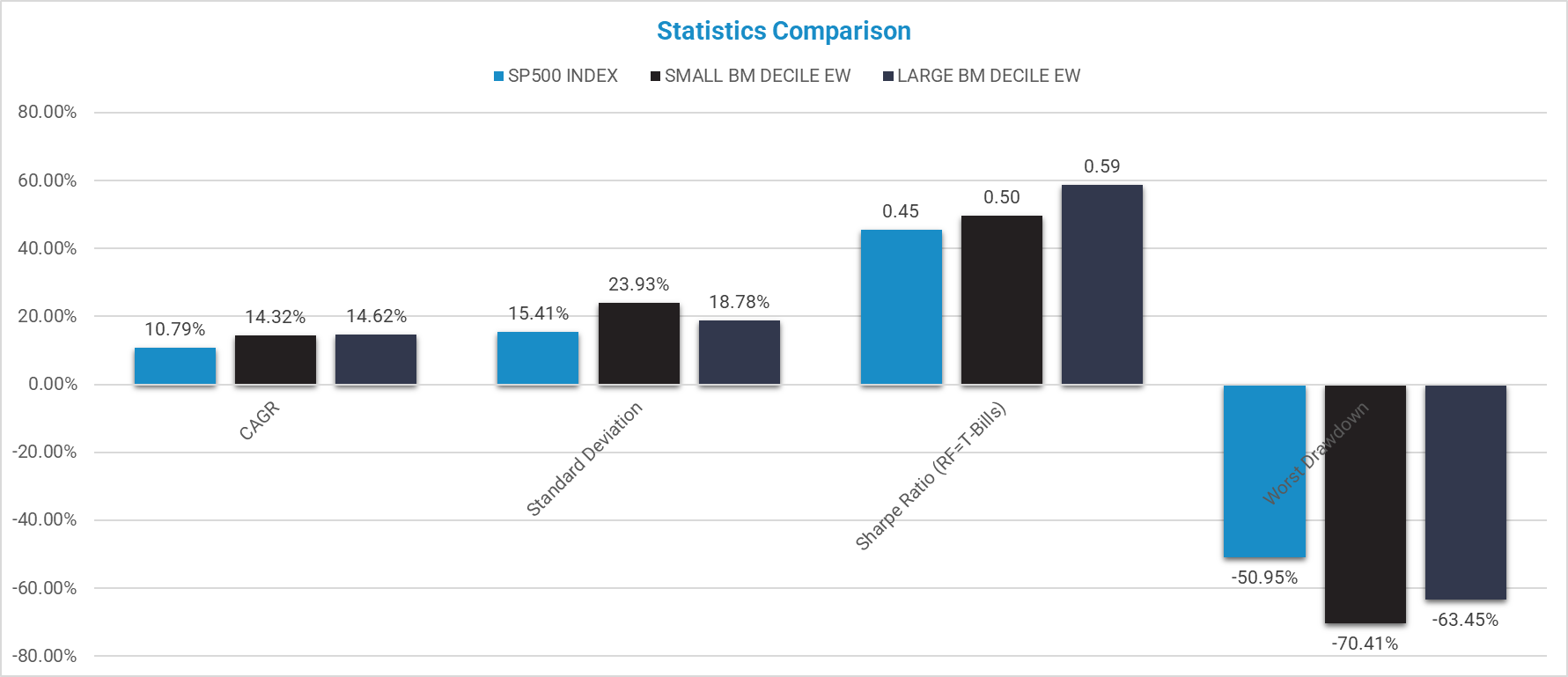

Key Result: Large-cap value stocks outperform small-cap value stocks on an absolute and risk-adjusted basis.

Here are the detailed stats:

Wait a second!

That can’t be true. All the research suggests value works better in small-caps. I tested it on Ken French’s website!

Don’t worry, the date on Ken Fench’s website is correct, but the portfolios from that website are crafted in a different way…

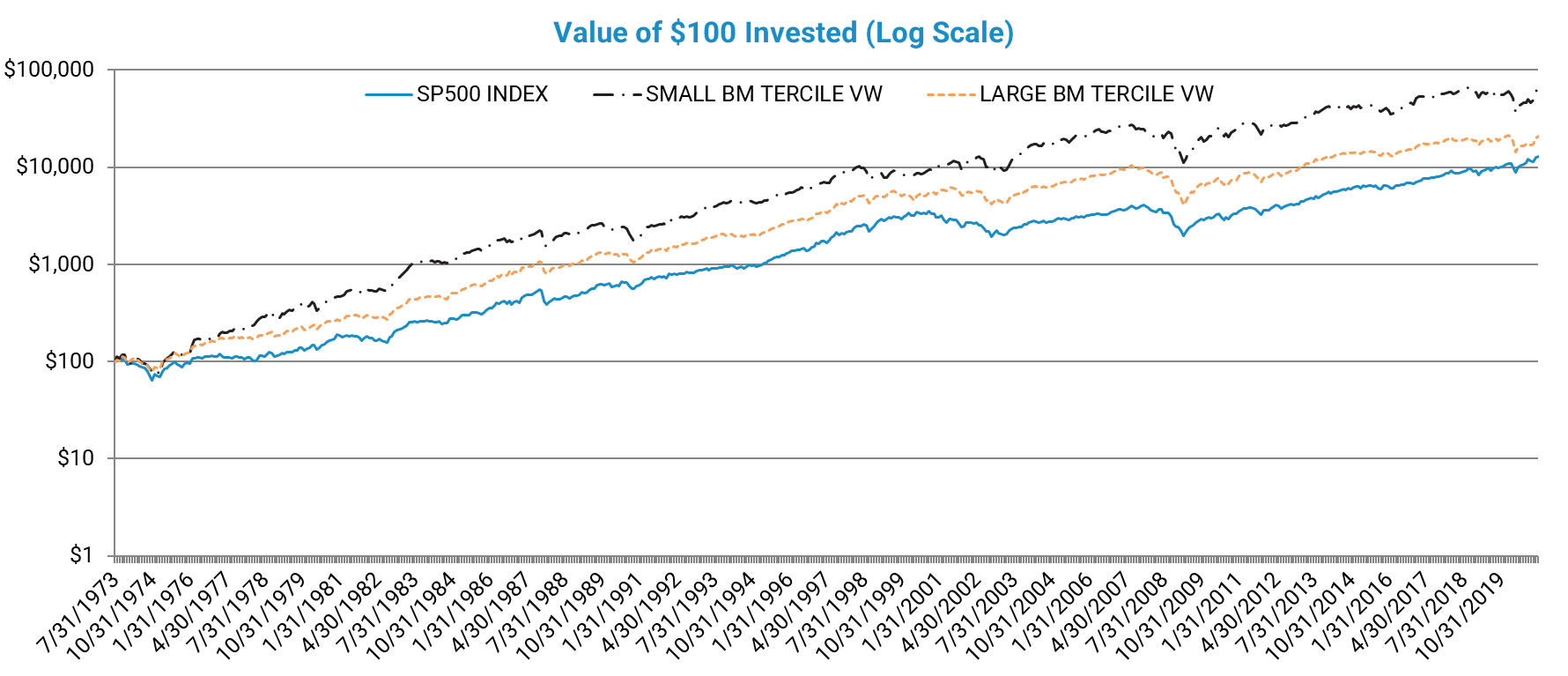

Below we look at the typical small-cap value and large-cap value chart, which compares value-weighted(4) large-cap and small-cap portfolios and looks at tercile sorts, not decile sorts.

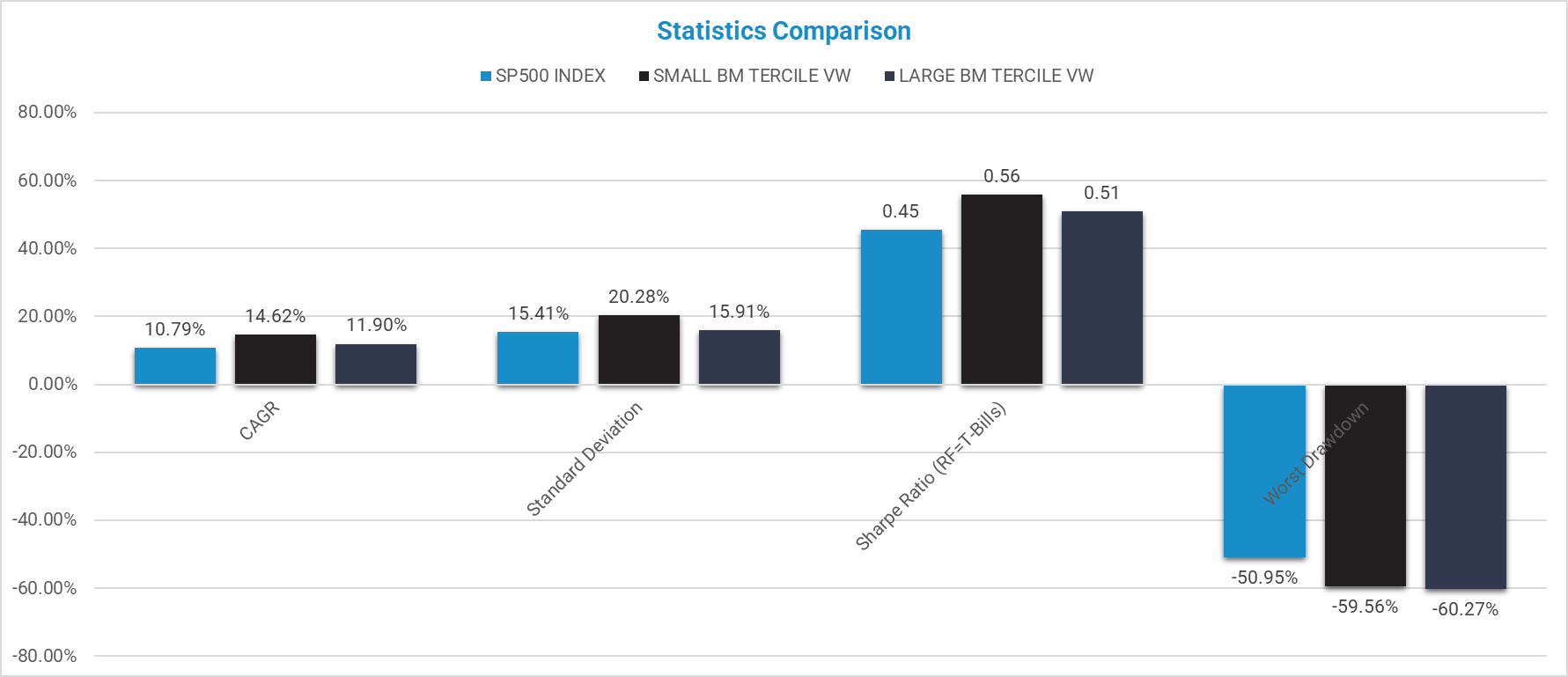

Eureka! We can replicate the result generated from data on Ken French’s website.

Here are the statistics:

What is the point of the exercise above? The point is that evidence-based investors want to invest on robust and reliable fact patterns, not results that can change dramatically via cherry-picked portfolio formations.

Why are the portfolios above fragile? Simple: Size doesn’t matter when it comes to value investing. Valuation does.

Let’s go for an intuitive example with low complexity. For example, if you can buy a portfolio with an average P/E of 5x and a market cap of $10B, this will, using historical datasets, outperform a portfolio with an average P/E of 8x and a market cap of $500mm. Why? Size doesn’t drive expected returns — valuation does.(5)(6) [/ref]

The reason this result may be surprising to readers is that size and value investing have never really been explored in a simple-to-understand way for non-PhDs. Fortunately, Jack’s latest research paper solves this problem!

Let’s dive into what I feel are the key points of Jack’s published paper.

Point #1: Long-Only Value Investing is Different than Long-Short Value Investing

As many readers know, academic research papers often study so-called zero investment long/short factor portfolios. But in the real world, most investors often don’t invest in these portfolio structures (outside of AQR and a few other providers)–they invest in long-only portfolios.

Why does Jack bring this up?

Well, many investors cite research that speaks to long/short portfolio analysis, and this analysis may not apply to their long-only portfolio decisions. This topic is addressed in more depth here.

Bottom line: if you are investing in long-only factor portfolios, focus on research that studies long-only factor portfolios, not long-short factors.

Point #2: Portfolio Formation Matters…a lot.

At the outset of this post, we made it clear that how one forms a portfolio can significantly drive results. By manipulating several decision points — 1) equal-weight vs. value-weight and 2) decile vs. tercile sorts — we can tell a story that large-cap value dominates small-cap value, or we can tell a story that small-cap value dominates large-cap value (the story most often told). But the important thing to note is these are both “stories” because they cherry-pick aspects of the data to highlight a particular argument.

Jack’s paper cuts through the stories told on size and value investing and conducts a robust study that looks at long-only portfolios with various valuation metrics, various portfolio formation techniques, and various geographies and sample time periods.

Throughout the paper, Jack breaks the top 3000 largest companies into the biggest 1000 firms (“large caps”) and the next largest 2000 firms (“small caps”). This breakdown is done to reflect how practitioners think about the marketplace and should be more applicable to long-only investors than research that uses NYSE percentile breakpoints.(7)

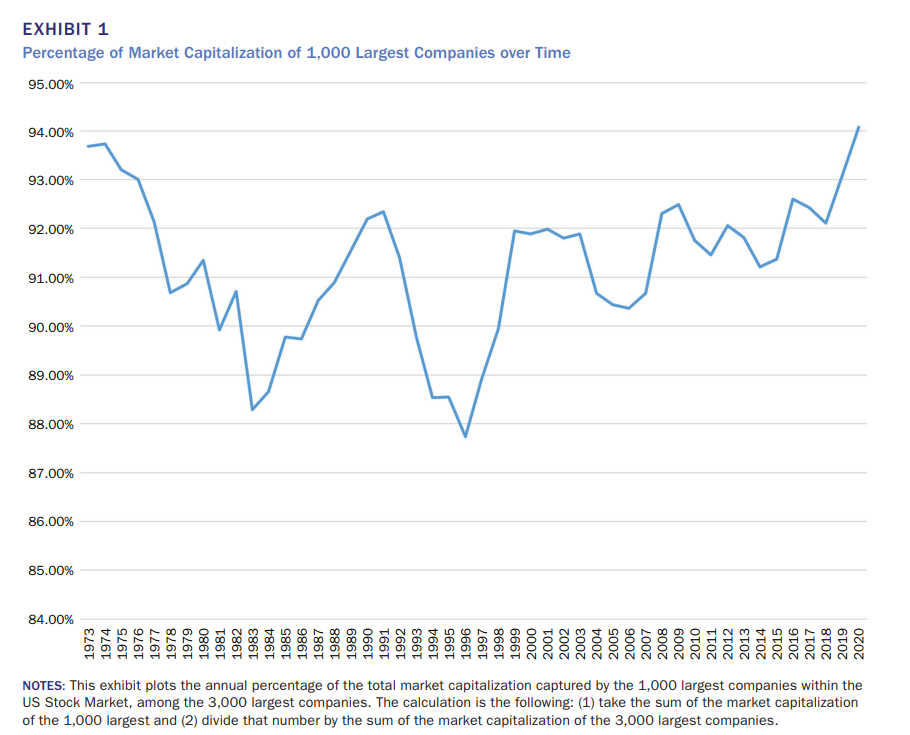

The breakdown of what percentage of the market resides in these respective buckets is in the chart below:

In general, large caps represent the vast majority of the investment universe, but this varies over time. Important to note, that mega-caps, at times, can represent a large portion of a portfolio if the portfolio has “value-weight” construction versus equal-weight construction. Take a simple example. Let’s say you sort the universe of stocks on P/E and find Apple in your portfolio and then stock X, which has a $100 billion market cap — not exactly “small”. Apple, which currently(8) has ~ 7.5% weight in the entire S&P 500, and a market cap of nearly $3 trillion, if dumped into a so-called “value portfolio” with two stocks, would represent 97% of the portfolio ($3T / $3.1 Trillion). Is this value-weighted portfolio really representative of the value factor? Or is it representative of Apple?

In order to avoid the noise tied to market-cap, or “value-weighted” portfolios, Jack focuses his results on how equal-weight large-cap portfolios compare to both value-weighted and equal-weighted small-cap portfolios.

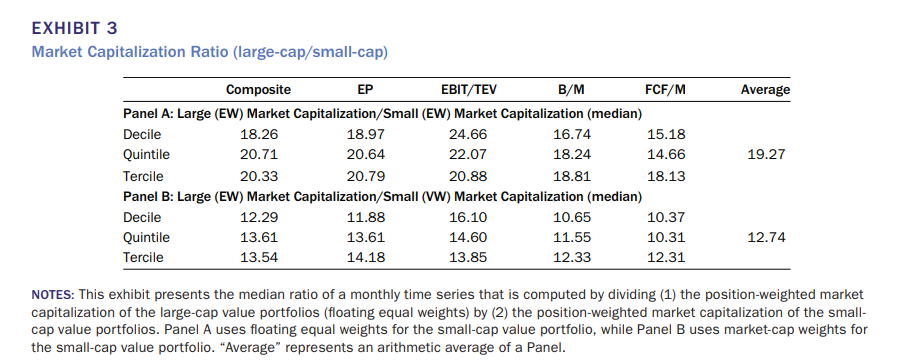

But before one claims that equal-weight large-cap portfolios are the same as small-cap portfolios, let’s look at the median ratio of the market caps of these portfolios over time:

The equal-weight large-cap portfolios are always at least 10x as large as the different small-cap portfolios. To be clear, equal-weighting large-cap portfolios isn’t equalizing the size characteristic, it is simply eliminating hidden noise in market-cap-weighted large-cap portfolios.

Point #3: Surprise! Large-Cap and Small-Cap Value Investing Earn Similar Returns

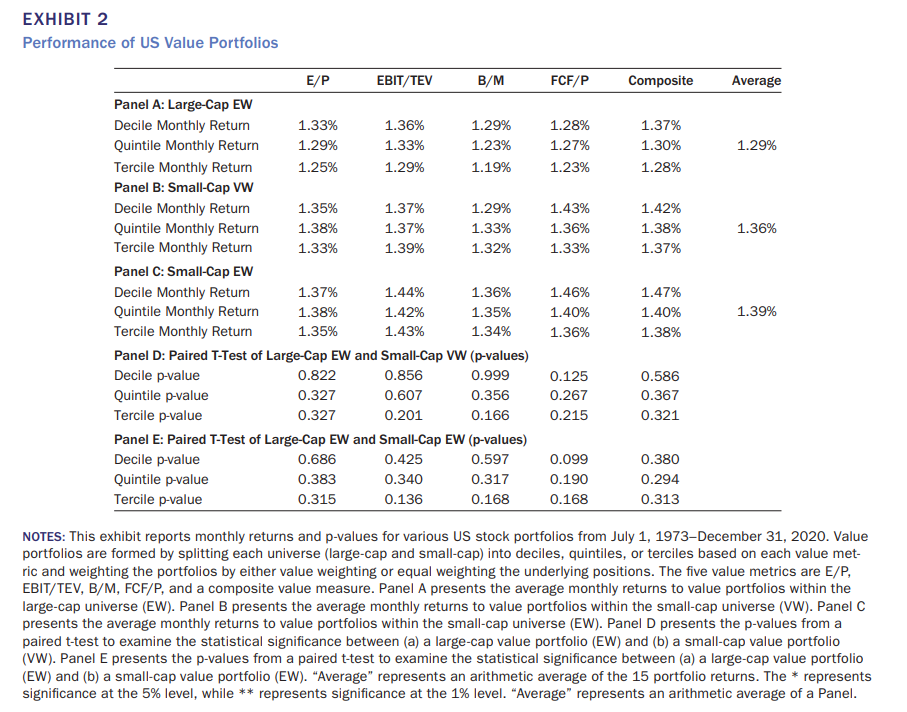

Jack slices and dices the results in a variety of ways, but here are the summary results for the US market:

Summary: no difference in average returns between large-cap and small-cap portfolios.

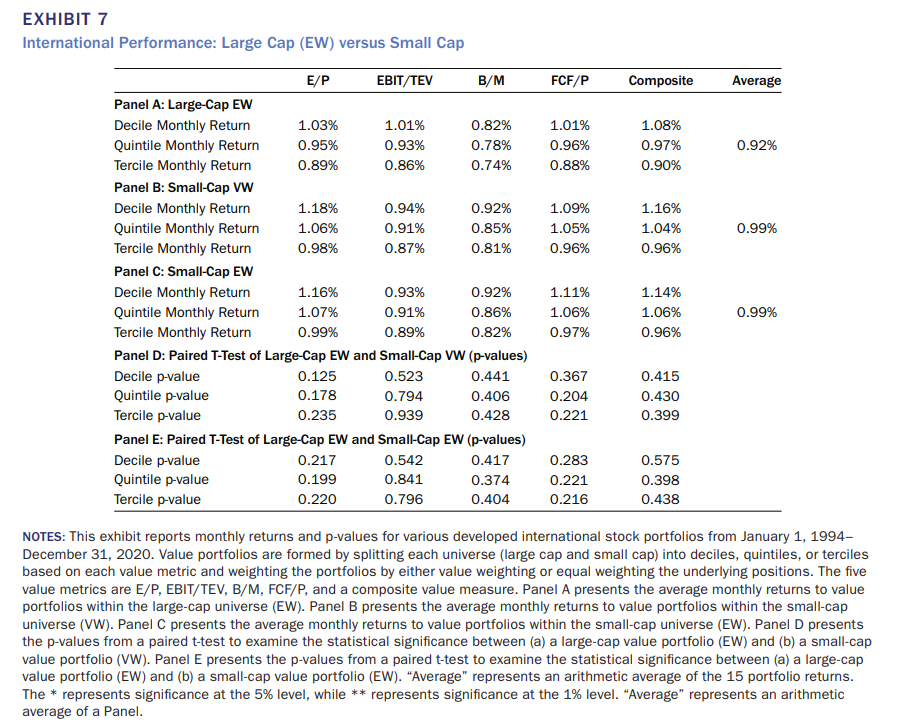

What about international markets?

Summary: no difference in average returns between large-cap and small-cap portfolios.

There you have it.

The small-cap sacred cow has been slaughtered.

Conclusions

We highly recommend you study this paper in-depth because there is a high chance that the results will be shocking to many. One can only publish so many tables and results in a peer-reviewed journal, but you can be sure that every stone was turned when Jack conducted this research. Of course, please share your replication results and questions with our team. Our goal is to bring transparency to the long-only value investing debate.

I hope you enjoy reading this paper as much as I did. I really learned a lot, and the analysis gave me more confidence in investing in mid and large-cap value strategies, as opposed to only investing in small-cap value, which is also interesting, but not more interesting than value investing, in general.

Finally, if you love small-cap investing, you should really like equal-weight large-cap value investing — similar expected returns with almost no holdings overlap (which may provide diversification opportunities). One should also consider that all of the results in this paper are on hypothetical portfolios that assume no trading costs. If we believe that trading costs are higher in smaller and more illiquid stocks (Exhibit 4 in the paper highlights that large-cap value portfolios are 10x+ more liquid than small-cap value portfolios), we’d expect transaction costs to degrade small-cap portfolios relatively more than large-cap portfolios.

References[+]

| ↑1 | 10+ years ago, we managed a small-cap value version of our quantitative value strategy. But we dismissed it based on the research described in the paper under discussion. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Summary here via Larry Swedroe |

| ↑3 | The source paper has full details on how portfolios are created. All returns are total returns and include the reinvestment of distributions (e.g., dividends). The time period analyzed is from 7/1/1963 to 12/31/2020. |

| ↑4 | stocks weighted by their market-cap weight relative to the other stocks in a portfolio |

| ↑5 | controlling for other factors, especially beta. |

| ↑6 |

The research in this paper isn’t the first to make this point:

|

| ↑7 | There is nothing wrong with the academic approach, but it does add confusion for practitioners |

| ↑8 | 6/12/2023 |

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.