We just wrote a piece for Forbes on financial bubbles in the lab. Punchline: investors initially underreact to fundamentals, then they overreact, and eventually prices correct. But how common are crashes? Ben has some interesting thoughts, but the results are limited to the US market. Now, one of my favorite academic authors — Prof. Bill Goetzmann — has a new paper that speaks to understand the frequency and dynamics of “bubbles” throughout history and across multiple global markets (i.e., the real-world lab!).

Here is the abridged abstract:

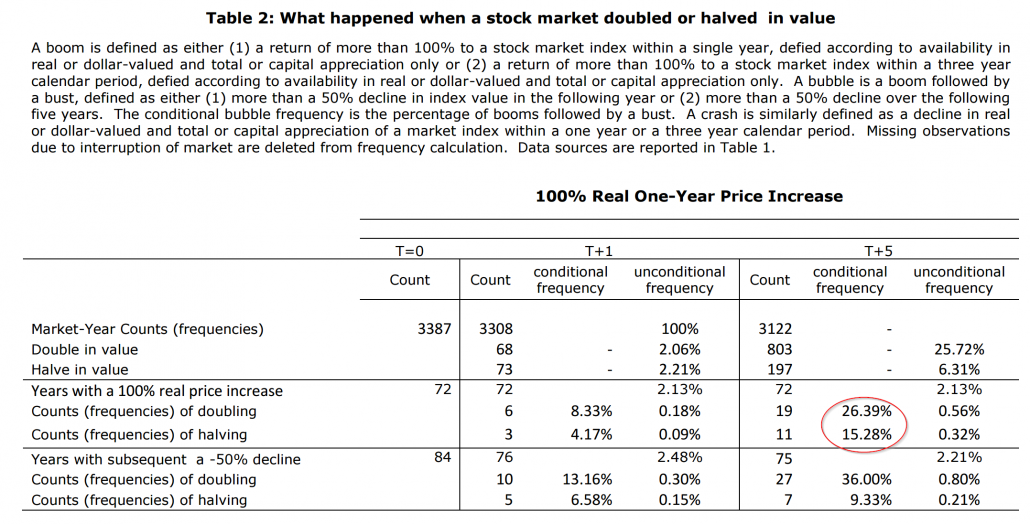

… In this paper I examine the frequency of large, sudden increases in market value in a broad panel data of world equity markets extending from the beginning of the 20th century…The chances that a market gave back it gains following a doubling in value are about 10%. In simple terms, bubbles are booms that went bad. Not all booms are bad.

The table below highlights some interesting points. The biggest point is that following a doubling of prices, the probability over the next 5 years of another double is 26.39%, but the probability of losing 50% is 15.28%. So big price movements occurring over short periods (i.e., “bubbles”) are more likely to continue, not burst.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

A few key learnings points that I gleamed from the paper:

- Bubbles are rare, empirically. But bubble chatter is common.

- Most large increases in prices are not followed by huge crashes. In fact, the opposite is true: larger price increases are more likely to be followed by large price increases, relative to a a large price decrease (i.e., a crash).

- Focusing on avoiding bubbles can come at a great expense — crash protection may cause an investor to forego the equity risk premium. This analysis layers on a higher burden of proof for market timing and/or downside protection models.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.