Asset Management within Commercial Banking Groups: International Evidence

- Miguel Ferreira, Pedro Matos and Pedro Pires

- The Journal of Finance, Fall 2018

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category.

What are the Research Questions?

- Do commercial bank-affiliated funds underperform unaffiliated funds, as well as funds that are affiliated with other types of financial conglomerates (e.g., investment banks and insurance companies)?

- Does the extent of the underperformance of commercial bank-affiliated funds increase with the relative size of the lending division and the degree of overweighting of the bank’s lending client stocks?

- Are there differences across countries?

- Are the results driven by the possibility that affiliated funds attract less talented managers?

What are the Academic Insights?

By testing a comprehensive sample of more than 29,000 survivorship bias-free open-end equity mutual funds domiciled in 28 countries over 2000-2010, the authors find:

- YES- On average, commercial bank-affiliated funds underperform unaffiliated funds by about 92 basis points per year as measured by four-factor alphas. Additionally, they obtain similar results when using alternative measures of performance such as benchmark-adjusted returns, gross returns, or buy-and-hold returns

- YES- Affiliated funds underperform more when the ratio of outstanding loans to assets under management is higher, which indicates a more pronounced conflict of interest. Additionally, they find that bank-affiliated funds’ portfolio holdings are biased toward client stocks over non-client stocks and bank-affiliated funds with higher portfolio exposure to client stocks (in excess of the portfolio weights in passive funds that track the same benchmark) tend to underperform more

- YES- “Chinese walls” between bank lending and asset management activities are more strictly enforced and fund investors’ rights are better protected in common-law countries such as the United States compared to civil-laws ones. In the sample of U.S.-domiciled funds, they find less pronounced underperformance and no relation between performance and measures of conflicts of interest with the lending division. In general, the authors find that conflicts of interest are less pronounced in markets with stronger laws and regulations and in bank-based countries compared to market-based ones. The level of bank and fund management companies concentration matters too

- NO- The “client stocks” (defined as those firms that obtain a loan for a bank) a fund buys underperform the client stocks a fund sells in the group of funds that overweight more client stocks. These funds, however, do not underperform in the trading of non-client stocks. Moreover, funds that overweight fewer client stocks do not underperform in the trading of client stocks. These results do not support the skill hypothesis.

Why does it matter?

This study shows that bank-affiliated fund underperformance is driven by a conflict of interest between the bank’s lending business and the asset management business. Specifically, it results from a double agency problem in that fund managers put aside the interests of one principal (the fund investor) in order to benefit another principal (the parent bank).

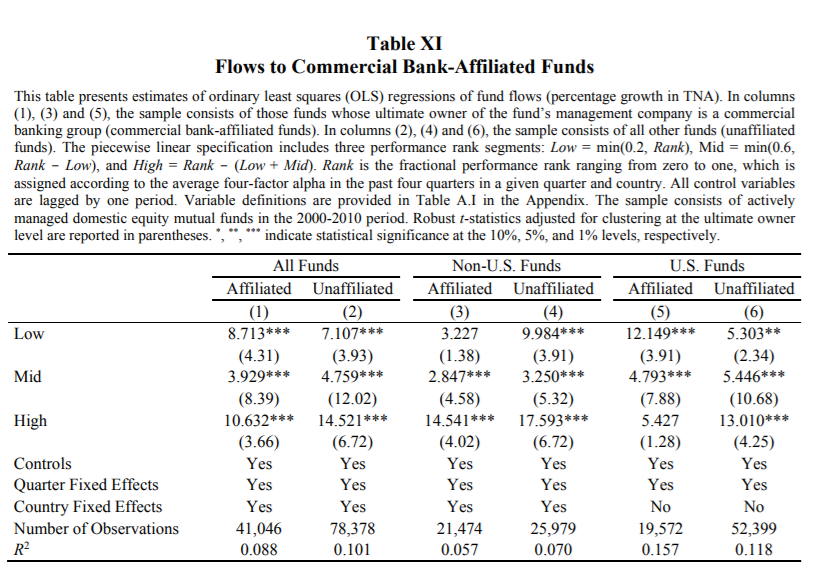

The Most Important Chart from the Paper:

Table 11 reports the estimates of fund flow-performance sensitivity regressions for the sample of all funds as well as for the samples of non-U.S. and U.S. funds. Results show that that the clientele of bank-affiliated funds outside the United States is less responsive to fund performance and exerts less monitoring. In fact,, the estimates in columns (3) and (4) show that affiliated funds have less flow-performance sensitivity than unaffiliated funds in the sample of non-U.S. funds: a 10-percentile increase in performance rank over the prior year increases unaffiliated fund flows by 4.0%(=0.1×9.984×4) per year for the bottomquintile,1.3%per year for the middle three quintiles,and 7.0%per year for the top quintile,while it increases affiliated fund flows by 1.3% for the bottom quintile, 1.1% for the middle three quintiles, and 5.8% for the top quintile. The sensitivity of affiliated fund flows to poor performance is statisticallyinsignificant, which suggests that affiliated fund investors (typically,retail investors) exhibit inertia.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Abstract

We study the performance of equity mutual funds run by asset management divisions of commercial banking groups using a worldwide sample. We show that bank‐affiliated funds underperform unaffiliated funds by 92 basis points per year. Consistent with conflicts of interest, the underperformance is more pronounced among those affiliated funds that overweight the stock of the bank’s lending clients to a great extent. Divestitures of asset management divisions by banking groups support a causal interpretation of the results. Our findings suggest that affiliated fund managers support their lending divisions’ operations to reduce career concerns at the expense of fund investors.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.