According to Christian mythology, the Holy Grail was the dish, plate or cup with miraculous powers that were used by Jesus at the Last Supper. Legend has it that the Grail was sent to Great Britain, where a line of guardians keeps it safe. The search for the Holy Grail is an important part of the legend of King Arthur and his court.

For many investors, the equivalent of the Holy Grail is finding the fund manager that can exploit market mispricings by buying undervalued stocks and perhaps shorting those that are overvalued. While it’s easy to identify those managers with great performance after the fact, there’s no evidence of the ability to do so before the fact. For example, there are dozens, if not hundreds, of studies confirming that past performance is a poor predictor of the future performance of active managers. That is why the SEC requires that familiar disclaimer:

Past performance does not necessarily predict future results.

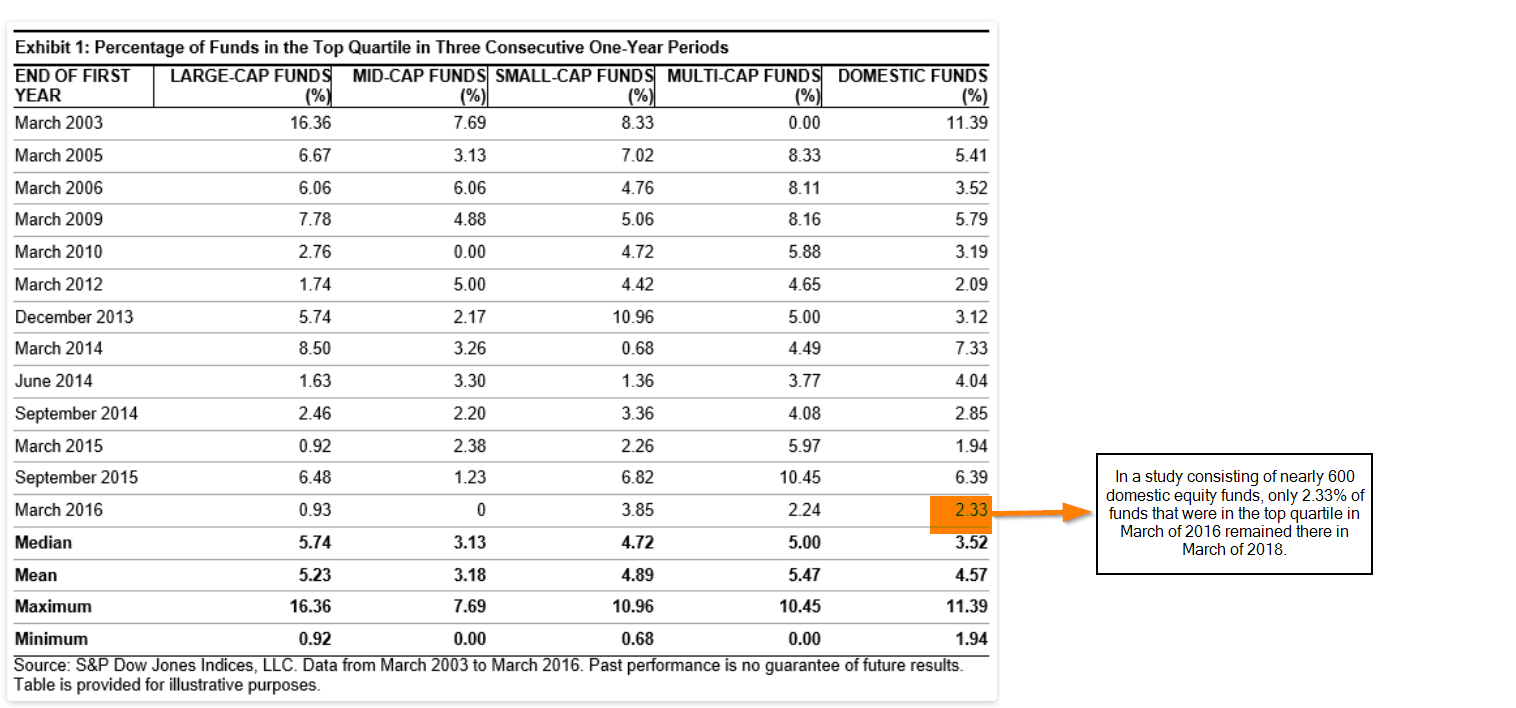

These studies find that, beyond a year, there is little evidence of performance persistence. The only place we find it (beyond that which we would randomly expect) is at the very bottom—poorly performing funds tend to repeat. And the persistence of poor performance isn’t due to poor stock selection. Instead, it is due to high expenses.(1)

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) tells us that the lack of persistence should be expected—it’s only by random good luck that a fund is able to persistently outperform after the expenses of its efforts. But there is also a practical reason for the lack of persistence—successful active management sows the seeds of its own destruction.

Jonathan Berk, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley (he’s now at Stanford), suggested the following thought process in his 2005 paper “The Five Myths of Active Portfolio Management”:

Who gets money to manage? Well, since investors know who the skilled managers are, money will flow to the best manager first. Eventually, this manager will receive so much money that it will impact his ability to generate superior returns and his expected return will be driven down to the second-best manager’s expected return. At that point investors will be indifferent to investing with either manager and so funds will flow to both managers until their expected returns are driven down to the third best manager. This process will continue until the expected return of investing with any manager is the benchmark expected return—the return investors can expect to receive by investing in a passive strategy of similar riskiness. At that point investors are indifferent between investing with active managers or just indexing and an equilibrium is achieved.”

Berk went on to point out that the manager with the most skill ends up with the most money. He added:

When capital is supplied competitively by investors, but ability is scarce, only participants with the skill in short supply can earn economic rents. Investors who choose to invest with active managers cannot expect to receive positive excess returns on a risk-adjusted basis. If they did, there would be an excess supply of capital to those managers.

In other words, it’s not investor capital that is scarce (in which case it would expect to earn the economic rent); it’s the ability to generate alpha.

Supporting Evidence

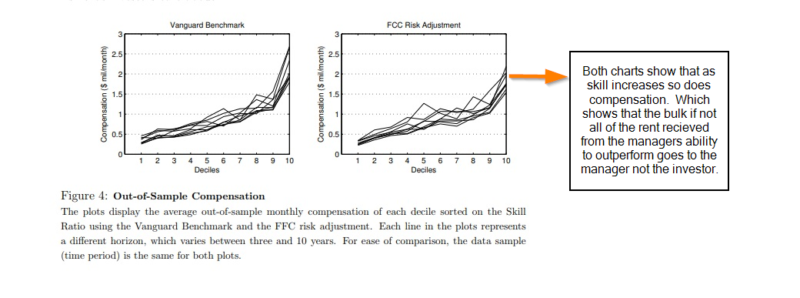

In 2015, Berk, with co-author Jules van Binsbergen, took another look at the issue in their study “Measuring Skill in the Mutual Fund Industry.”(2) Confirming his hypothesis, they found that investors recognize skill and reward it by investing more capital with better funds, which earn higher aggregate fees. However, they also found that “the value weighted net alpha was a statistically insignificant -1 basis point per month.”

The fact that, as theory suggests, any alpha has gone to the fund sponsor, not investors, is an important insight. Just as the EMH explains why investors cannot use publicly available information to beat the market (because all investors have access to that information, and it’s therefore already embedded in prices), the same is true of active managers. Investors should not expect to outperform the market by using publicly available information to select active managers. Any excess return will go to the active manager (in the form of higher expenses).

The process is simple. Investors observe benchmark-beating performance, and funds flow into the top performers. The investment inflow eliminates return persistence because fund managers face diminishing returns to scale. Studies such as “Scale Effects in Mutual Fund Performance: The Role of Trading Costs” and “Fund Tradeoffs” provide evidence supporting the logic of Berk’s theory, showing funds face diseconomies of scale as trading costs rise.

Success Sows Seeds of Destruction

There is another reason why successful active management sows the seeds of its own destruction. As a fund’s assets increase, either trading costs will rise, or the fund will have to diversify across more securities to limit trading costs. However, the more a fund diversifies, the more it looks and performs like its benchmark index.(3)

It becomes what is known as a “closet index fund.” If it chooses this alternative, its higher total costs must be spread across a smaller number of differentiated holdings, increasing the hurdle of outperformance.

As my co-author Andrew Berkin and I discuss in “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha,” several trends lead toward ever-increasing difficulty in generating alpha:

- Academic research is converting what once was alpha into beta (exposure to factors in which one can systematically invest, such as value, size, momentum and profitability/quality). Investors can access those new betas through low-cost vehicles, such as index mutual funds and ETFs. And as David Mclean and Jeffrey Pontiff demonstrated in their 2016 study “Does Academic Research Destroy Stock Return Predictability?”, the publication of research leads to reduced factor premiums.

- The pool of victims that can be exploited is persistently shrinking. Retail investors’ (“dumb money”) share of the market has fallen from about 90 percent in 1945 to about 20 percent today.

- The amount of money chasing alpha has dramatically increased. Twenty years ago, hedge funds managed about $300 billion; today it’s about $3 trillion. And according to the 2018 Investment Company Fact Book, at the end of 2017 there were more than 16,800 mutual funds versus roughly 100 active funds 60 years ago.

- The costs of trading are falling, making it easier to arbitrage away anomalies.

- The absolute level of skill among fund managers has increased.

This last point confuses many investors. They think that if the absolute level of skill in the mutual fund industry has increased, it should be easier to produce alpha. However, what so many people fail to comprehend is that in many forms of competition (such as chess, poker or investing), the relative level of skill plays a more important role in determining outcomes than the absolute level of skill. What’s referred to as the “paradox of skill” means that even as skill level rises overall, luck can become more important in determining outcomes if the level of competition is also rising.

In a 2014 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal, Charles Ellis, one of the most respected people in the investment industry, observed: “Over the past 50 years, increasing numbers of highly talented young investment professionals have entered the competition. … They have more-advanced training than their predecessors, better analytical tools, and faster access to more information.” Legendary hedge funds, such as Renaissance Technology, SAC Capital Advisors and D.E. Shaw, hire Ph.D. scientists, mathematicians and computer scientists. MBAs from top schools, such as Chicago, Wharton and MIT, flock to investment management armed with powerful computers and massive databases.

For example, Dimensional’s CIO Gerard O’Reilly has a Caltech Ph.D. in Aeronautics and Applied Mathematics. And Andrew Berkin, head of research at Bridgeway Capital Management, has a Caltech B.S. and University of Texas Ph.D. in Physics and is a winner of the NASA Software of the Year award. (Full disclosure: My firm, Buckingham Strategic Wealth, recommends Dimensional and Bridgeway funds in constructing client portfolios.) According to Ellis, the “unsurprising result” of this increase in skill is that “the increasing efficiency of modern stock markets makes it harder to match them and much harder to beat them, particularly after covering costs and fees.”

Further evidence that the ability to generate alpha is shrinking was found by S&P Director of Global Research & Design Berlinda Liu in her study “Does Performance Persistence of Active Managers Vary Over Time?” Liu examined past active versus passive scorecards and concluded: “A review of the performance persistence figures over time shows a downward trend over the longer-term horizon for equity funds, indicating an increasing difficulty to stay at the top.”

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Summary

There is plenty of evidence that not only does skill exist in the active management industry, but the level of skill is increasing. In addition, investors are able to identify the skill and reward it with cash flows. However, just as theory suggests, the scarce resource (the ability to generate alpha) gets to keep any economic rent. In addition, as Robert Stambaugh points out in his January 2019 paper, “Skill and Fees in Active Management,” the fact that active managers are more skillful results in the market discovering and correcting any mispricings more quickly.

He concluded:

The results here show that an increase in overall skill can imply a smaller equilibrium amount of fee revenue.

He added:

If greater skill spells less revenue, an upward trend in skill represents a potential challenge for the active management industry.

That’s on top of the increasing hurdles we discussed—including a continued reduction in the number of noise traders. In other words, to date, the decline in the level of active management is not resulting in more mispricing, but less.

The bottom line is that the active management industry is facing strong headwinds, including the race to the bottom in fees for passive strategies. Stambaugh noted:

The result has been that in the case of equity mutual funds, for example, over the period from 2001 to 2016, active management lost 15% in its share of total AUM while reducing its fee (expense ratio) by 30 basis points.

Stambaugh added this observation:

Of course, an industry of competing active managers cannot decide to calm that headwind by becoming less skilled. Applying more skill is in each manager’s individual interest, because more-skilled managers make more than less-skilled managers, as also implied by the model presented here.

The good news is that not only is the cost of both passive and active strategies coming down, but despite the decline in the share of active investing, the markets have become more efficient, not less, as many have warned would be the case. And there doesn’t seem to be anything that would change the direction of the trends.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Though recently Alpha Architect did find an instance where past performance may be indicative of potential performance persistence: hedge funds that outperform in difficult periods, tend to do better in the future. Here is the blog post. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | More discussion is available here. |

| ↑3 | A deeper discussion is available here. |

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.