One of the big problems for the first formal asset pricing model developed by financial economists, the CAPM, was that it predicts a positive relation between risk and return. But empirical studies have found the actual relation to be flat, or even negative. Over the last 50 years, the most “defensive” (low-volatility, low-risk) stocks have delivered both higher returns and higher risk-adjusted returns than the most “aggressive” (high-volatility, high-risk) stocks.

The literature provides several proposed explanations for the low volatility anomaly. The most prominent is that faced with constraints and frictions, investors looking to increase their return choose to tilt their portfolios toward high-beta securities to garner more of the equity risk premium. This extra demand for high-beta securities, and reduced demand for low-beta securities, may explain the flat (or even inverted) relationship between risk and expected return relative to the predictions of the CAPM model.

Regulatory constraints can also be a cause of the anomaly. Regulators typically do not distinguish between different stock types, but merely consider the total amount invested in stocks for determining regulatory capital requirements. Investors desiring to maximize equity exposure but minimize the associated capital charge are drawn to high-volatility stocks because they provide more equity exposure per unit of capital charge.

The academic literature has also posited that constraints on short selling (such as charters prohibiting it) and fear of unlimited losses can cause stocks to be overpriced because the optimists are expressing their views by pessimists may be unable, or unwilling, to do so.

And finally, the research demonstrates that both mutual funds and individual investors tend to hold the stocks of firms that are in the news more. In other words, they tend to buy attention-grabbing stocks that experience high abnormal trading volume, as well as stocks with extreme recent returns. Attention-driven buying may result from the difficulty that investors have in searching through the thousands of stocks they can potentially buy. Such purchases can temporarily inflate a stock’s price, leading to poor subsequent returns. Attention-grabbing stocks are typically high-volatility stocks, while boring low-volatility stocks suffer from investor neglect. The attention-grabbing phenomenon is therefore another argument supporting the existence of the volatility effect.

In fact, prior research demonstrating that companies that experience unusually high news flows experience shocks in their price volatility inspired David Blitz, Rob Huisman, Laurens Swinkels, and Pim van Vliet to study the relationship between media attention and the low volatility anomaly.

Their June 2019 study “Media Attention and the Volatility Effect” tested the following two hypotheses:

- The low-volatility effect disappears for stocks with high media attention.

- The low returns for high-volatility stocks are caused primarily by stocks of companies that appear most frequently in the news.

They took the total number of news articles per company as a sorting variable (the raw data) and then adjusted for market capitalization (larger companies are more likely to receive media attention). Their database covered the period 2000-2018 and included U,S., developed international, and emerging market stocks.

The following is a summary of their findings:

- There is an increasing pattern between volatility and media attention.

- Media attention increases for stocks in higher volatility groups, and volatility increases for stocks in higher media attention groups—‘glittery’ stocks tend to be the stocks with relatively high volatility, while the ‘boring’ stocks that the media does not write about tend to have relatively low volatility.

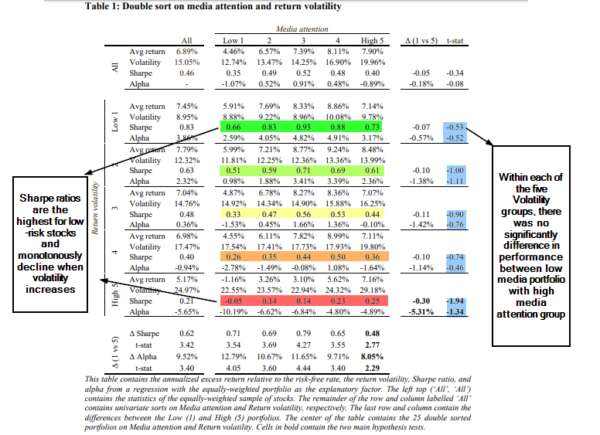

- For stocks with similar media attention, the Sharpe ratios are the highest for low-risk stocks and monotonously decline when volatility increases. This finding rejects the first hypothesis.

- Within each of the five volatility groups, there was no statistically significant difference in performance between the low-media-attention portfolios compared to the high-media-attention groups. This finding rejects the second hypothesis.

- The findings were consistent across U.S., developed international, and emerging markets, and in various tests of robustness.

Source: Media attention and the volatility effect. The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Blitz, Huisman, Swinkels, and van Vliet concluded:

Based on these findings, we reject that the attention-grabbing hypothesis explains the volatility effect. Of course, this conclusion relies on the assumption that the number of media articles covering a stock is a good proxy for investor ‘attention grabbing’.

Summary

The literature provides us with many possible explanations for the low volatility anomaly, including this behavioral one—investor overconfidence. Investors (including active fund managers) are overconfident. The result of overconfidence is that we have a violation of the assumptions used by the CAPM, which is predicated on rational information processing. The impact on the volatility effect is that, if an active manager is skilled, it makes sense to be particularly active in the high-volatility segment of the market because that segment offers the largest rewards for skill. However, this results in excess demand for high-volatility stocks.

While there are many possible explanations, what does seem clear is that many of them come from either constraints and/or agency issues driving managers toward higher-volatility stocks. Given that there does not seem to be anything on the horizon that would have a dampening impact on these issues, it appears likely the anomaly can persist. In addition, human nature does not easily change. Thus, there does not seem to be any reason to believe that investors will abandon their preference for “lottery ticket” investments. And limits to arbitrage, as well as the fear and costs of margin, make it difficult for arbitrageurs to correct mispricings. The bottom line is that low volatility has predicted low volatility and likely will continue to do so. And while it seems likely that the constraints and limits to arbitrage will allow the high volatility stocks to continue to underperform, whether the high returns to low volatility strategies will continue to present an anomaly is another question. One reason is that popularity leads to cash flows which can cause premiums to either shrink or disappear. For those interested, I addressed this question in my Advisor Perspectives article of June 19, 2019.

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.