Tesla (TSLA) breached the $100 billion market capitalization in January 2020 and became the most valuable car manufacturer globally. However, valuing the company is challenging given the growth profile, complexity of the business, and erratic CEO. It is not yet profitable and cash flow is negative, which means that traditional valuation metrics based on historical data are currently less applicable to Tesla.

Investors could consider that Tesla sold less than 400,000 cars in 2019, compared to more than 6 million for Volkswagen (VW), which is valued at $87 billion. Tesla might seem extraordinarily expensive from this perspective, but that is similar to previous years.

Tesla and a few similar names like Netflix represent the antithesis of value investing and have been defying the expectations of most investors, especially of short-sellers. However, there is still very little research to suggest that systematically buying expensive stocks is a good idea — the approach only works if you can find the Tesla’s and Netflix’s ahead of time. On the flip side, are cheap stocks, often referred to as value stocks in academic/factor research. Despite value’s abysmal performance in the US in recent memory, research still supports the value factor, which has been validated in global equity markets as well as across different asset classes.

As many investors are realizing, factor investing is simple, but not easy. For example, it’s one thing to review historical performance charts of the value factor, but its an entirely different thing to actually live through a long stretch of relatively poor performance! Perhaps factor investors can rely on the fundamental valuation of a factor to understand future expectations of that factor? In this short research note, we will explore this question and look at equity factors, their valuations, and their expected returns.

What’s the bottom line? Despite strong intuitions that suggest cheaper factor valuations lead to stronger future returns, the evidence is mixed at best and differs across factors. Relying on the valuation of a factor to time allocations is a noisy signal and should not be heavily relied upon as a definitive indicator of future success. The one area where the results are strong is on the value factor — when the “value of the value factor” is relatively cheap, the performance on value is generally more favorable in the future.

Factor Valuation Spreads

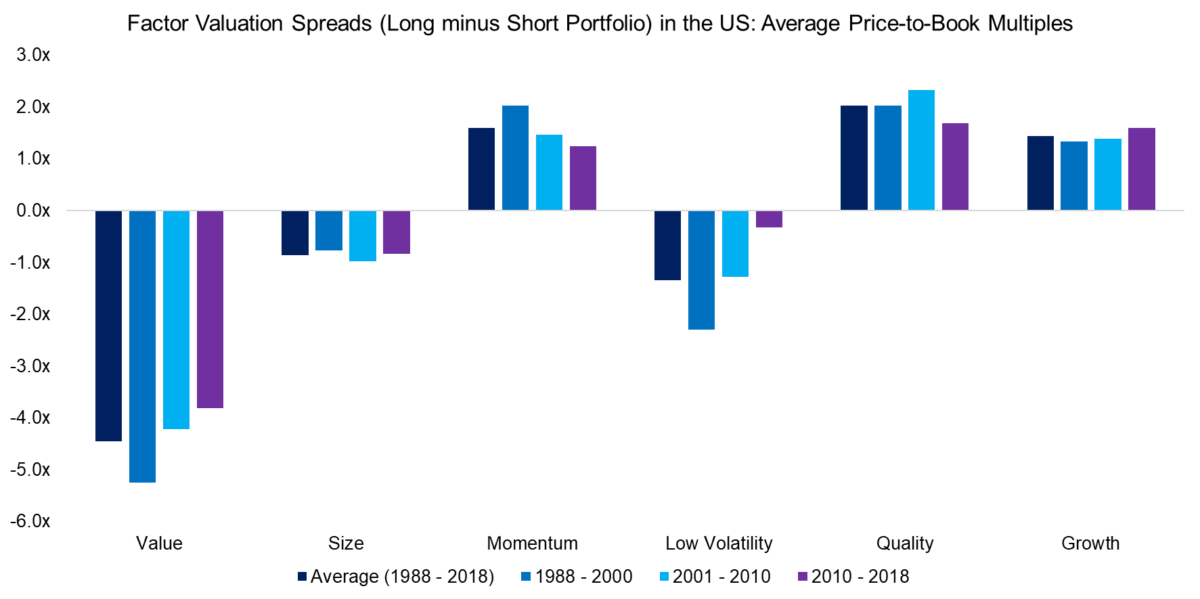

Factors can be valued like stocks based on fundamental metrics. We calculate the average price-to-book multiples of the long and short portfolios of common equity factors as well as the difference between those valuations, which is termed the valuation spread. The higher the spread, the more expensive a factor is from a valuation perspective.

It is worth highlighting that factors exhibit structurally different valuation spreads. The Value factor has a negative spread per definition as the long portfolio contains stocks trading at cheap valuations while the short portfolio is comprised of expensive stocks with high multiples. Other factors like Momentum or Quality feature positive spreads, on average.

The analysis below highlights the valuation spreads from 1998 to 2018 as well as for each of the decades for six common equity factors, which are defined in line with academic and industry standards. Despite the US equity market experiencing various boom-and-bust cycles during the last 30 years, the average spreads for each factor were approximately comparable across the decades.

Factor Valuations & Expected Returns

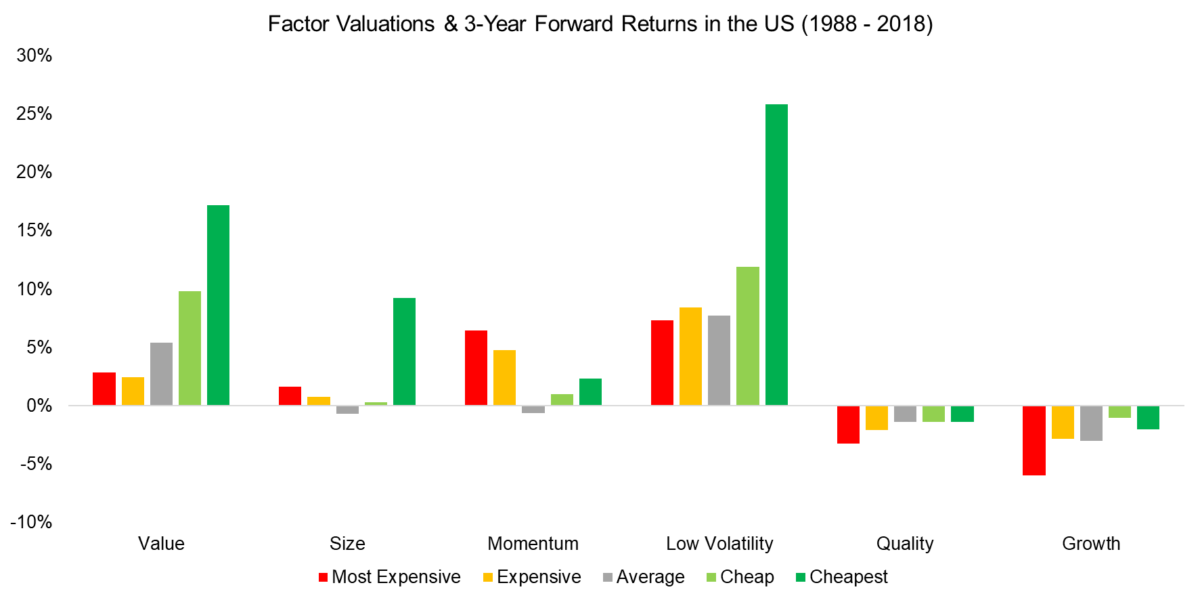

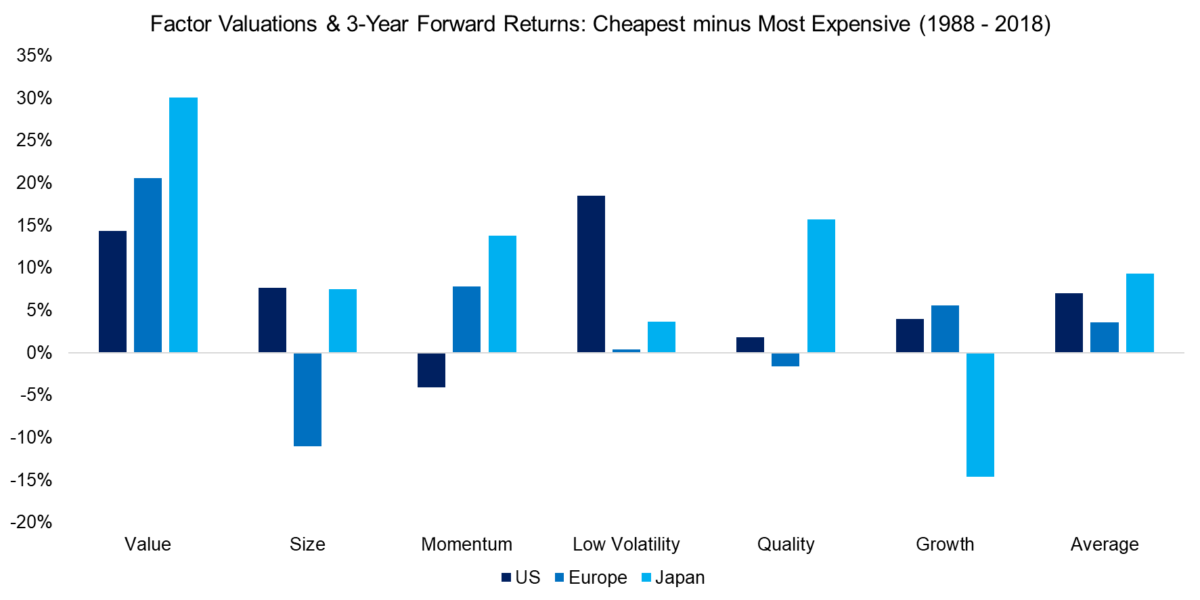

We split the valuation spread time series covering the period from 1988 to 2018 into quintiles that represent different valuation categories ranging from most expensive to cheapest. Each of these categories contains approximately the same number of data points. We then measure the 3-year forward returns on a daily basis and aggregate the results.

The analysis highlights that the subsequent performance was higher when the factor was trading at a cheap valuation than at an expensive one in the US stock market. It is an almost linear relationship for all factors, except for Size and Momentum.

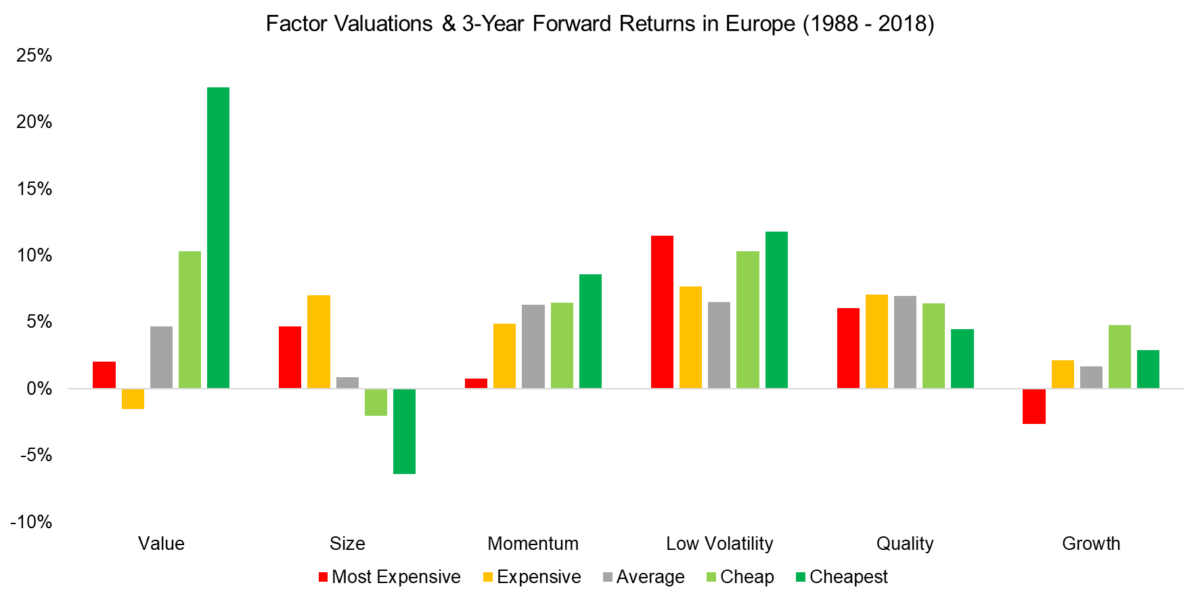

We replicate the analysis in the European stock market, which provides a less homogenous perspective. The factor valuation mattered for Value, Momentum, and Growth, but seemed less meaningful for other factors.

Factor performance in Europe and globally is correlated and investors behave similarly, so there are few arguments why a valuation-based approach should have been less effective than in the US.

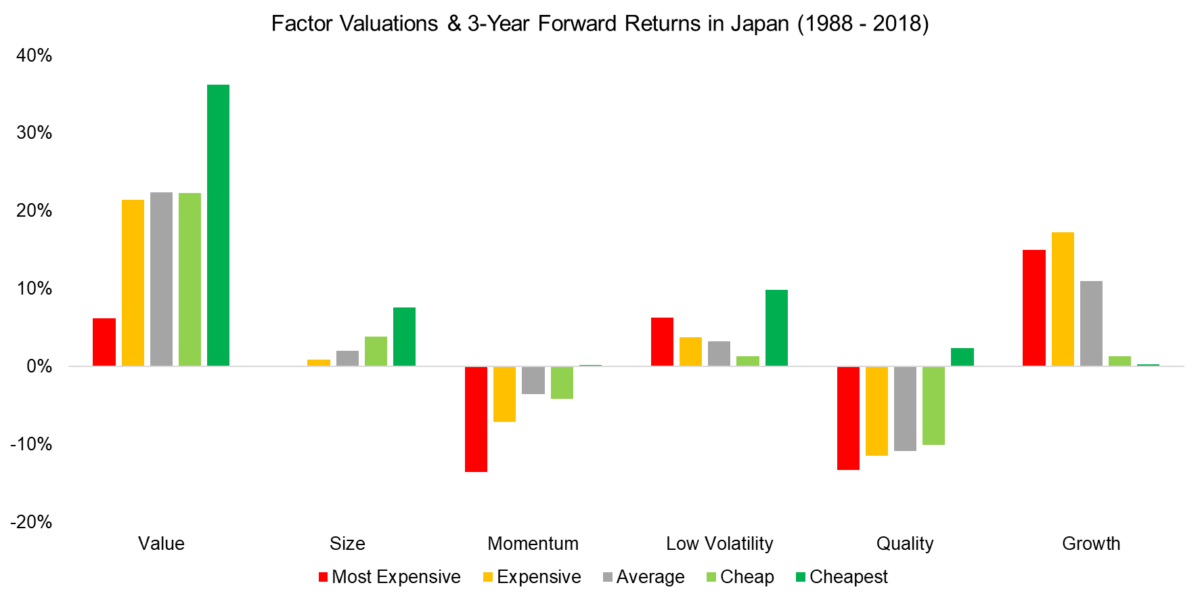

Similar to the results in the US stock market, in Japan, a cheaper factor valuation led to higher returns than an expensive one for the majority of factors. Some literature highlights that certain factors like Momentum performed worse in Japan than in the US or Europe, but typically also expresses strong support for the Value factor and other mean-reversion strategies, which should provide fertile grounds for investors contrasting between cheap and expensive factors.

Cheap vs Expensive Factors

Finally, we aggregate the results from all regions and calculate the difference in returns when valuations were the cheapest and most expensive. We observe that the valuation-based approach to factor investing has only led to consistently positive returns across the regions for the Value factor. However, although there is less consistency across the other factors, it was effective on average.

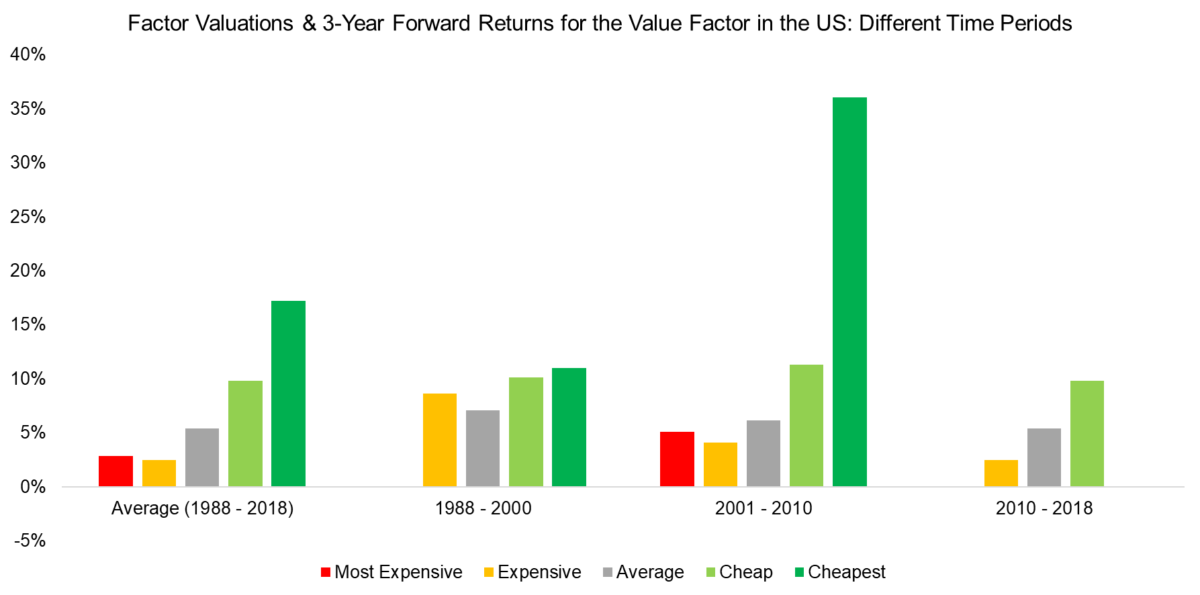

Although we have established that the valuation spreads have not changed structurally over the last three decades, it might be that the positive returns from buying factor exposure when trading cheaply and selling when expensive could be largely attributed to a certain time period.

Using the Value factor in the US as a case study, we analyze the valuations and subsequent returns per decade between 1988 and 2018. The results highlight that the valuation-based approach to factor investing worked relatively consistent across time. The most significant period was between 2001 and 2010, which includes the implosion of the tech bubble. Cheap stocks like Berkshire Hathaway significantly outperformed expensive stocks like Pets.com or Webvan, generating large returns for the Value factor.

Further Thoughts

Despite these positive results, allocating to factors based on their valuations is unlikely attractive on a stand-alone basis, which is a concept we’ve hit on pretty hard in the past here, here, and here. The core issue is that the framework requires investors to have zero exposure to certain factors for multiple years when they are trading expensive to very expensive, which would demand extreme discipline. Especially given that some factors like Low Volatility generated positive returns across regions even though the factor was trading at high valuations.

However, a valuation-based framework to factor investing can be integrated into a multi-metric approach to factor risk management, which is more sensible as well as a more robust approach.

About the Author: Nicolas Rabener

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.