Another Alpha Opportunity Bites the Dust

In 1998, Charles Ellis wrote “Winning the Loser’s Game,” in which he presented evidence that while it is possible to generate alpha and win the game of active management, the odds of doing so were so poor that it’s not prudent for investors to try. At the time, roughly 20 percent of actively managed mutual funds were generating statistically significant alphas (they were able to outperform appropriate risk-adjusted benchmarks). Today, that figure is much lower—about 2 percent (even before considering the impact of taxes). In our 2015 book, “The Incredible Shrinking Alpha,” my co-author Andrew Berkin and I described several major themes behind this trend toward ever-increasing difficulty in generating alpha:

- Academic research is converting what once was alpha into beta (exposure to factors in which you can systematically invest, such as value, size, momentum, and profitability/quality). And investors can access those new betas through low-cost vehicles such as index mutual funds and ETFs.

- The pool of victims that can be exploited is persistently shrinking. Retail investors’ share (stocks held in their brokerage accounts) of investment dollars had fallen from about 90 percent in 1945 to about 20 percent by 2008. Surely, it is much lower today And their share of trading is today is only about 10 percent.

- The amount of money chasing alpha has dramatically increased. For example, 20 years ago, hedge funds managed about $300 billion; today it is about $3 trillion.

- The costs of trading have fallen dramatically, making it easier to arbitrage away anomalies.

- The absolute level of skill among fund managers has increased—the competition has gotten tougher.

These trends have contributed to the decline in the ability of active managers to generate alpha. In his wonderful book “Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought” Andrew Lo, while acknowledging that the markets are not perfectly efficient, described the process by which markets adapt, becoming ever more efficient as entrepreneurs exploit inefficiencies (anomalies) post-publication—the adaptive markets hypothesis.

Latest Evidence of Increased Market Efficiency

Anthony A. Renshaw, author of the paper “The Weakening Index Effect,” published in the Summer 2020 issue of the Journal of Index Investing, provided us with another example of shrinking/disappearing anomalies, increasing the hurdles active managers face in their attempts to generate alpha. The Index Effect is the phenomenon where stocks that are added to an index experience positive excess returns in the days before being officially added, while stocks that are removed from an index experience negative excess returns. Renshaw noted that the Index Effect has been documented since S&P first started announcing index changes in advance in October 1989. Following is a summary of his findings:

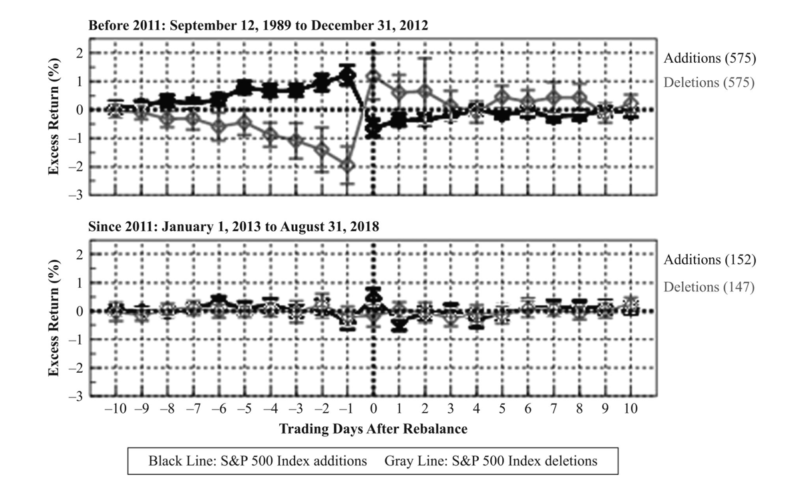

- For the S&P 500 Index, prior to 2011, many of the returns had been surprisingly large: −17.0% for deletions in 1989–1992; +9.3% for additions in 1998–2000. However, for the last three-years (2016-18), the 10-day buy-and-hold returns were just +15 bps for additions and −23 bps for deletions, both of which are smaller than their standard errors.

- As you can see in the following charts, prior to 2011 there was a pronounced index effect in the S&P 500. Post 2011 it not only weakened, it virtually disappeared— there is no statistically significant difference in returns between additions and deletions.

- The weakening of the Index Effect has been particularly pronounced for indexes composed of large- and mid-cap stocks.

- The Index Effect still can be observed in many (but not all) indexes with small-cap stocks. For example, for the S&P 1500 Index, the returns to the 10-day buy-and-hold strategy over the last three years (2016-18) were still an economically significant 4.9% for additions and −4.7% for deletions. However, the 1-day buy-and-hold was not effective for additions, and less effective for deletions.

- The results for the FTSE Developed Index are similar to those of the S&P 500 in that the magnitude of the Index Effect has weakened in recent years. The Index Effect is no longer present for additions. While still present for deletions, has been close to zero as recently as 2014–2016.

- The Index Effect continues to be present for unscheduled deletions but not for unscheduled additions. The unscheduled deletions have the following common characteristics: negative returns are associated with: low weight in the index (small stocks); low medium-term momentum; low profitability; low earnings yield; high volatility; and high market sensitivity (beta).

- The weakening of the Index Effect has occurred concurrently with a substantial increase in passive investing.

- ETF market makers (e.g., authorized participants) trade on price disparities as soon as they occur, eliminating any sustained positive or negative price movements—ETF trading improves liquidity and market efficiency.

- Due to limits to arbitrage, the Index Effect can still be found in some indexes with small-cap stocks and those with notably illiquid names.

Summary

One of the claims of active fund managers is that the rise of indexing and passive investing in general would make the markets less informationally efficient. It would also create more opportunities for exploiting index funds that focus on minimizing tracking error—they are forced to trade, and, thus, likely to take a loss when rebalancing occurs. If that were the case, the rise in passive investing would have led to an increase in the Index Effect. Yet, the exact opposite has occurred. The opportunities to generate alpha continue to shrink, making active investing more and more of a loser’s game.

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.