Box spreads represent an opportunity to borrow and lend via the options market at similar (and often better) rates than those available in the treasury bill market.

Traditionally, the box spread funding market has only been used by sophisticated hedge funds, market makers, and proprietary trading groups. However, there is no reason why retail investors and advisors can’t participate in the market.

The barrier to entry is education, but we are here to solve that issue. (It’s our mission!)

Here’s the bottom line: letting your money sit in a checking or brokerage account is almost decidedly NOT the best solution for your excess cash and short-term reserves. Treasury bills and money market funds are often better deals for the investor (and worse for the banks/brokers!), but they are not the only alternative.

Box spreads are also an option (no pun intended) and may represent the best after-tax, after-cost funding arrangement in the marketplace.

Let’s dig into box spreads!

First, Let’s Describe How a Treasury Bill Makes You Money

Unlike many other bonds, which pay coupons and a par value at the end of the bond’s life, a treasury bill pays interest via a discount to par value. Their construction is often referred to as a ‘zero-coupon’ bond. For example, if you bought a 1-year Treasury at $95, you would receive $100 in 1 year, implying a 5.26% return ($5/$95).(1)

If you want to keep track of treasury bill rates, you can always hit the data directly from FRED, and Treasury direct post its data here.

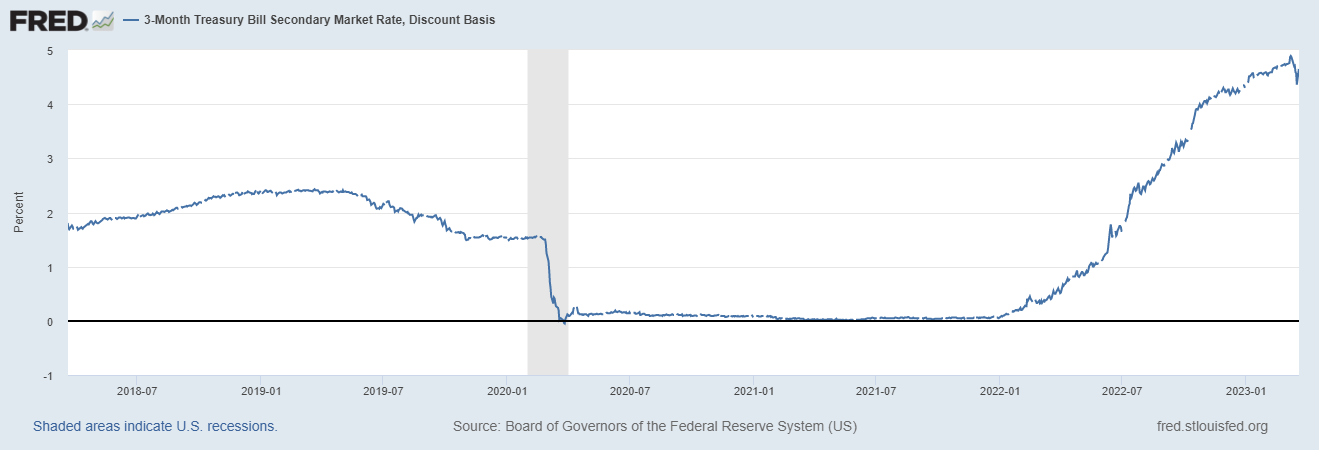

Below is a chart of recent 3- month rates:

Treasury bills have de-minimus credit risk (S&P rates the US Gov’t at AA+ with a stable outlook), can be a great place to stash short-term money, and the interest you earn isn’t subject to state tax (although the vast majority of the gains will be taxed as income — yuck!)

But treasury bills aren’t your only option for short-term cash reserves. Box spreads, constructed via the options market, represent a close alternative to the treasury bill from a risk/return perspective.

How Do Box Spreads Work?

Box spreads are not common knowledge, even among financial professionals. However, that does not mean that box spreads are new. Academics have been publishing research on box spreads for decades. For example, in 1985, Professors Billingsley and Chance published “Options Market Efficiency and the Box Spread Strategy” in The Financial Review. And just recently (2022), an incredible paper called “Risk-Free Interest Rates” was published in the Journal of Financial Economics.(2)

Academics are interested in studying box spreads because practitioners find them interesting: they represent an alternative, “Risk-free rate,” with similar risk and reward payoffs as treasury bills…

Wait a second…how in the heck can a basket of options have the same risk/reward as a treasury bill? Aren’t options risky?

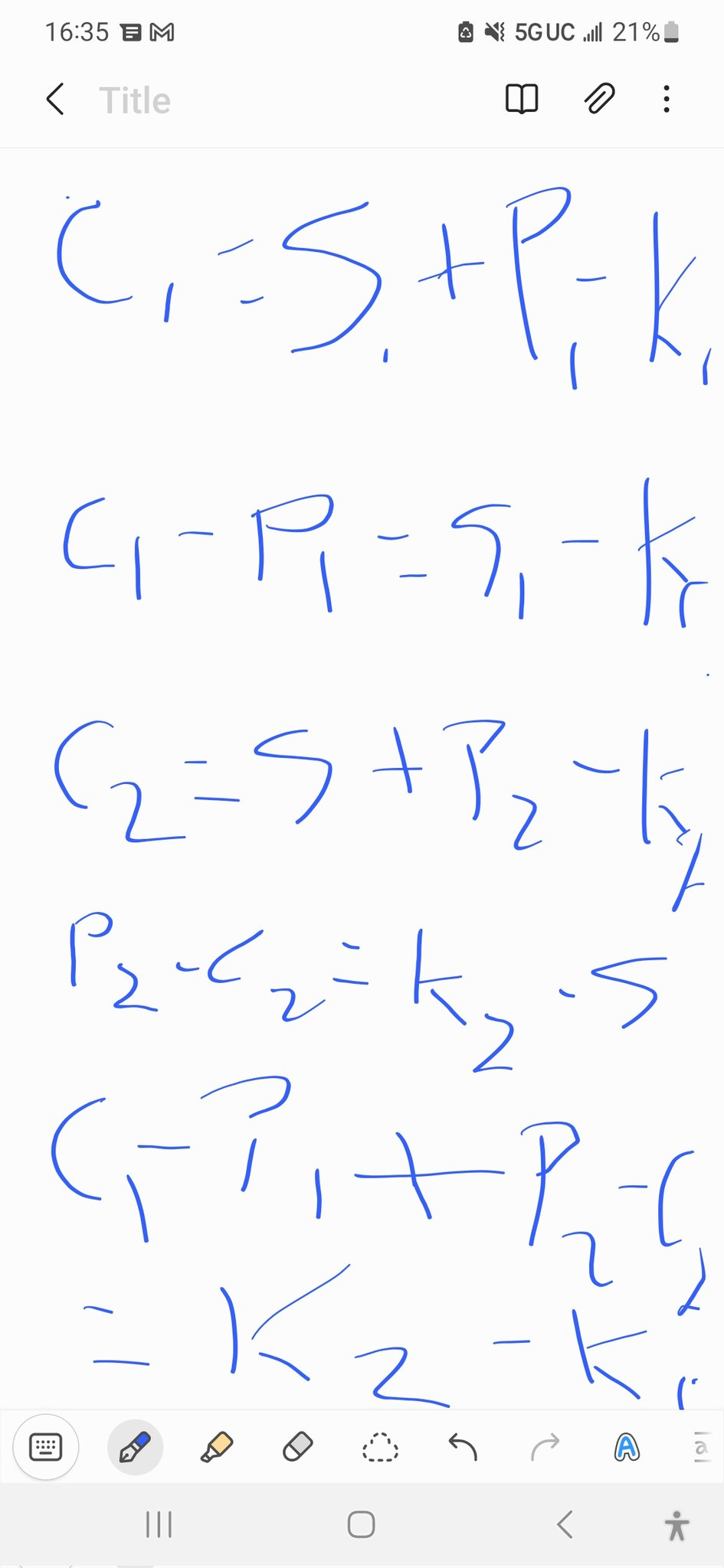

Enter math via put-call-parity…(3)(4)

Put-call-parity governs, via arbitrage relationships, how different options and underlying assets are tied together.

The box spread is no different and is subject to the put-call-parity relationship.

Let’s skip the math and go through the intuition of a box spread, how to create one, and why they don’t have stock market risk and act like treasury bills. (Here is a spreadsheet to help you understand the charts below). Please note that we will be discussing box spreads on SPX European-style options for simplicity. Box spreads can be implemented on many other assets (American style options should be avoided btw!), but that will complicate the following discussions.

To start, (SPX) box spreads consist of 4 option contracts:

- Long call on SPX

- Short call on SPX

- Long put on SPX

- Short put on SPX

A hypothetical example is the easiest way to understand why a box spread eliminates market risk.

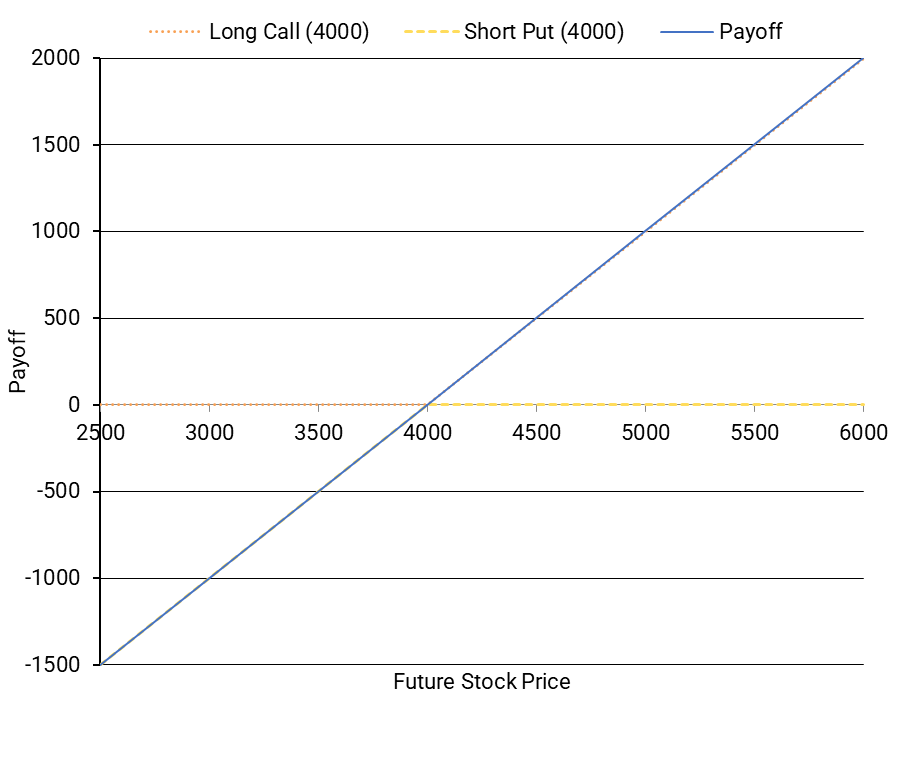

Consider the following option position:

- Long a call and short a put

- The strike price of $4,000 on both options

- 1-year expiration on both options

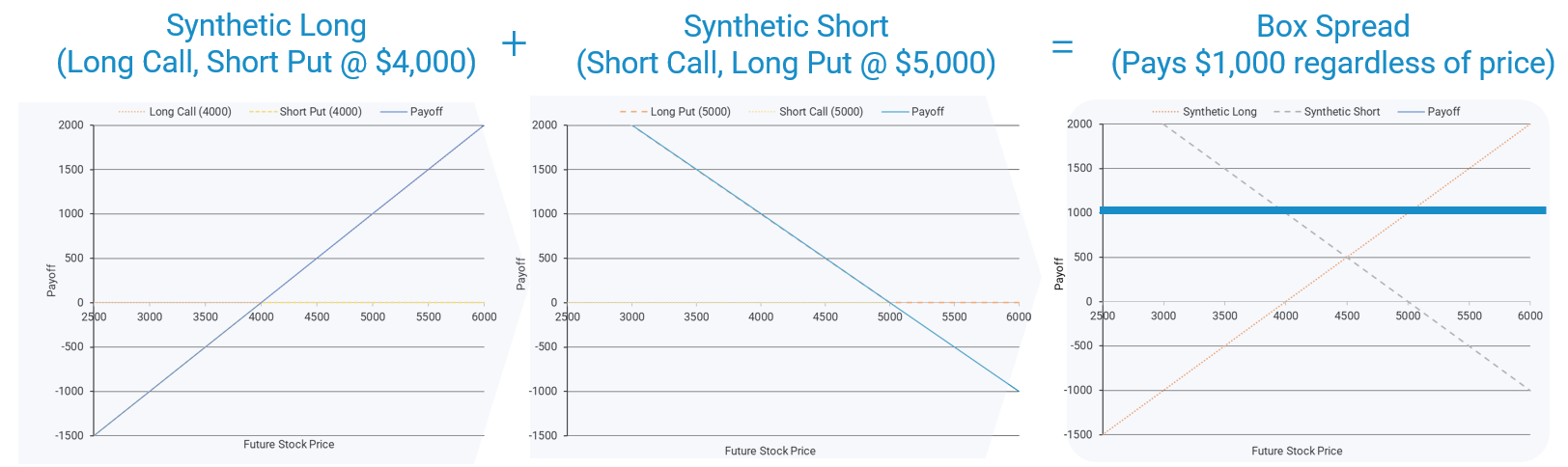

The payoff profile of this position is outlined below in blue:

What do you notice?

Well, the payoff profile resembles the exact profile of a long stock position delivered one year from now — if the price goes above $4,000, you make money, and if the stock price goes below $4,000, you lose money.

Congrats, via options, we just replicated a stock future!

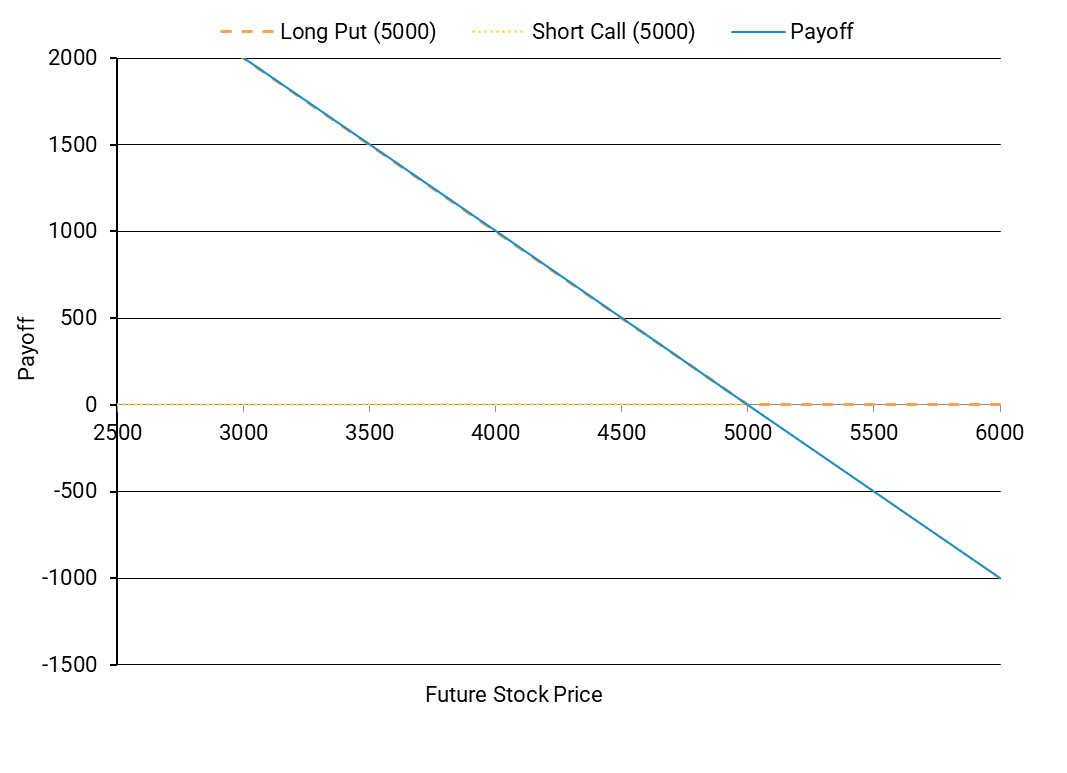

Let’s consider another option position: Long a put and short a call with a strike price of $5,000 and an expiration one year from now.

The payoff profile of this position is outlined below in blue:

This chart looks a lot like a short position in the stock!

You will lose money for every tick above $5,000 a year from now, and for every tick below $5,000 a year from now, you will make money.

Congrats–You just passed financial engineering 101 and now know how to use options to replicate a long and short stock futures position.

Where does the box spread come in?

Simple: we execute on the two option packages above.

- Synthetic long: we go long the call and short the put at $4,000.

- Synthetic short: we go long the put and short the call at $5,000.

What happens when you combine a long and short position on the same asset?

You eliminate all market risks.

In the case of box spreads, you are left with a guaranteed payoff of the spread in strikes between the synthetic long position and the synthetic short position, which is $1,000 in this example (i.e., $5,000 – $4,000).

Got it.

We buy/sell this 4-option package, which will deliver us $1,000, no matter the stock price, one year from now.

Awesome…how do we leverage this trade and become billionaires?

Unfortunately, markets are pretty efficient.

And if there is an opportunity to make $1,000, guaranteed, you aren’t going to pay $0 for that opportunity. What do you pay? $100? $500?

Errr…wrong…none of the above.

You’ll probably pay a price that locks in a return similar to 1-year treasury bills. For example, let’s say the treasury bill rate is 5.26%. Maybe the box spread cash flow setup looks as follows:

| Underlying | Current Price | Synthetic Long | Synthetic Short | Cash Outflow | Payoff at Expiration | Box Spread Return |

| SPX | 4,000 | -$2,950 | $2,000 | -$950 | $1,000 | 5.26% |

The synthetic long position costs you $2,950, and the synthetic short position gives you $2,000 for a net cash outflow of $950. But the box spread trade will deliver $1,000 a year from now. This implies that the return on this box spread is 5.26% ($50/$950), similar to the treasury bill rate.

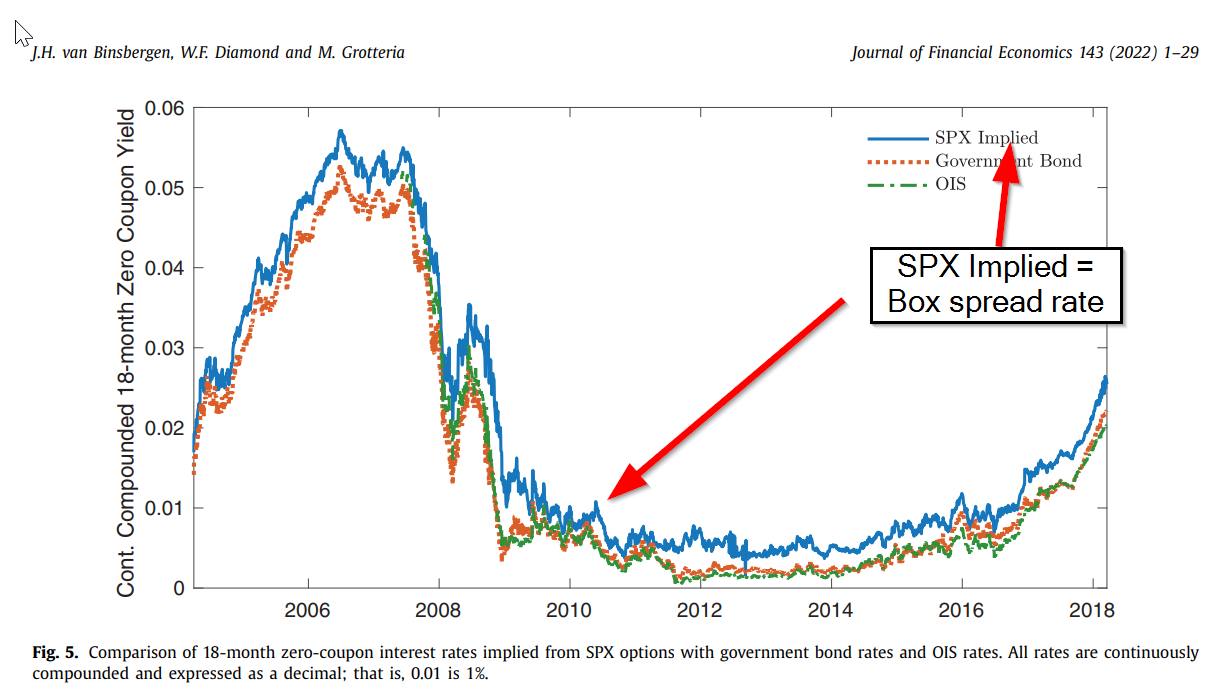

Side note: historically, box spread rates have always been higher than equivalent treasury bill rates, and there are many reasons to believe that will continue. See below for a chart from a recent JFE article on this topic. However, for our discussion, let’s assume that box spreads and equivalent treasury bills earn roughly the same returns.(5)

My old professor, Dr. Eugene Fama, is sure markets are efficient. And if two assets earn a similar return, it must be the case that the risk of these two assets is very similar. And now that we’ve determined that box spreads earn similar returns to treasury bills (often higher!), let’s dig in a bit more on the risk side of the equation.

What are the Counterparty Risks of Box Spreads?

The section above highlights that no market risk is tied to box spreads. One buys the 4-combination option strategy, and like magic, the spread in strikes will be delivered in the future.

But how can we be sure the spread in strikes will be delivered?

We need to know if the counterparty clearing these options contracts can pay up. All investments have some level of counterparty risk (including US government obligations). How does counterparty risk play out in the context of box spreads?

Unlike treasury bills, which the U.S. government directly backs, box spreads are cleared through the Options Clearing Corporation.

A summary of the credit situation for OCC and the U.S. government is below:

| Rating | Outlook | |

| US Sovereign Debt* | AA+ | Stable |

| Options Clearing Corporation** | AA | Stable |

** 2/14/2024 confirmed via email with OCC investor relations.

The OCC and the US government are equivalent from a credit rating services standpoint. In addition, the OCC is a SIFMU, or systematically important financial market utility, which means the federal reserve will (most likely) get involved if something is amiss at the OCC.

How has OCC faired throughout history?

The creditworthiness of the OCC has been proven many times over, including the 1987 crash and the 2008 financial crisis. To my knowledge, the OCC has never failed to clear an option transaction.

Below is a quote from the Risk-Free Interest Rates paper that discusses the risk tied to OCC-cleared options:

For our interest rates to be risk free, no meaningful credit risk in equity options traded on the CBOE can exist. We believe our options are effectively free of credit risk for several reasons. First, the CBOE requires investors to post margin and make daily variation margin payments, which ensures the safety of options except in the event of very extreme movements in the S&P 500. Second, the CBOE posts additional margin with the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC), which clears the options traded on the CBOE. In the event of a bankruptcy, derivatives are “supersenior” and exempt from the automatic stay, so derivatives traders can immediately seize the collateral backing their trades. The CBOE has an A credit rating and the OCC a AAA rating, so the odds of both institutions being unable to make payments is remote. The OCC is also considered a “Systemically Important Financial Market Utility” and has access to emergency liquidity support from the Federal Reserve. During the extreme stock market crash of 1987, the Federal Reserve intervened to ensure all derivatives contracts were successfully paid off (see Bernanke, 1990). Even the default of Lehman (active in the derivatives market) did not expose the OCC to losses, because Lehman’s collateral was sufficient to pay off all derivatives counterparties (Faruqui et al., 2018).”

Binsbergen, Diamond, and Grotteria, 2022, “Risk-free interest rates,” Journal of Financial Economics

Nothing in life is guaranteed, but OCC-backed options have similar counterparty risk to the US government.

How are Box Spreads Taxed?

Treasury bill gains are generally characterized as income,(6) the most onerous form of taxation. One benefit of treasuries is the income is generally not subject to state tax (this might matter if you live in California!).

The taxation of box spreads is complex; the tax rates (e.g., 25% or 40%) and tax character (e.g., income vs. capital gain) of options can differ from the taxation of treasury bills. The situation can get even more complex for index options, such as SPX, which are considered 1256 contracts, meaning 60% of their gains are taxed at long-term capital gains rates, and 40% are taxed at short-term capital gains rates.(7) One can layer on even more complexity via the ETF create/redeem basket mechanism, which is often used in the context of equity exchanges (but also available for options exchanges under certain circumstances).

Aye, caramba, my brain is already smoking a bit!

In short, the taxes on box spreads are well beyond the scope of this conversation, and one should ensure they explore the tax implications of box spreads and consult with their tax advisors for customized advice. We are not tax attorneys (although we’d love to get paid the same hourly rate as tax lawyers).

How can I use box spreads in practice?

The discussion above was primarily focused on buying simple SPX European-style box spreads (American options are a whole different beast!).

One could use an SPX box spread (1) instead of letting one’s money sit in their brokerage account and earn nothing, or (2) may be an alternative to buying money market funds and/or treasury bills.

Important to note, but not discussed in detail above, investors can also “borrow” from the box spread market by selling a box spread. You borrow money from the options market to fund your leverage in that scenario. Funding leverage via box spreads is often cheaper than borrowing from your broker via margin loans. If you are a sophisticated investor utilizing leverage to facilitate your investment strategy, you may want to explore using box spreads as a financing vehicle.

In summary, box spreads represent a powerful funding tool to lend and borrow via the options market. Unfortunately, many investors are unaware of this funding market. Still, we hope this post and our continuing education will help build awareness for box spreads and encourage investors to explore their use in their practice.

Feel free to reach out if you have any questions.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Treasury Direct has much more information on how these bonds work and how you can purchase them directly via their website. (Vanguard has a good summary here as well). See the appendix for more information.

Here is a video on the process of buying Treasuries: If you don’t want to open a treasury direct account and you are skittish about not knowing the rate you’ll receive before you bid, you can always buy and sell treasury bills via your brokerage account. The cheapest brokerage option we know of is Interactive Brokers, which outlines their costs here. (commission plus the bid/ask spread). But almost all brokers offer the ability to buy/sell bills on the secondary market and the costs are generally low. Of course, the challenge with investing directly in treasury bills is they are subject to interest rate risk — and the further you move out in time, the more interest rate risk one bears. Many investors like to set up ladders of treasury bills to try and ‘smooth’ our duration risk and/or target a specific duration (e.g., 1-3 months or 6-12 months) while also minimizing transaction costs (i.e., avoiding having to ‘roll’ bill positions before expiry). Some investors throw in the towel on the brain damage and buy mutual funds and ETFs that do this work on your behalf. There are many options for many types of investors. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | William Diamond, son of Nobel Prize winner Doug Diamond was a co-author — great academic research capability runs in the genes! Note, this post originally said that Doug Diamond was the author and was fixed on 12/19/2023. Sorry for any confusion and my apologies to William Diamond and his co-authors. |

| ↑3 | https://www.optionseducation.org/advancedconcepts/put-call-parity has a good piece on put-call-parity. |

| ↑4 |

https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-200x433.png 200w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-400x867.png 400w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-600x1300.png 600w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-709x1536.png 709w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-800x1734.png 800w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2.png 945w" sizes="(max-width: 945px) 100vw, 945px" /> https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-200x433.png 200w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-400x867.png 400w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-600x1300.png 600w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-709x1536.png 709w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2-800x1734.png 800w, https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/image-2.png 945w" sizes="(max-width: 945px) 100vw, 945px" /> |

| ↑5 | Box spreads traditionally earn higher returns than equivalent treasury bills. There are many reasons why this might be the case, but the recent 2022 paper argues this is for a ‘convenience yield.’ Below is a chart of historical box spread yields vs. equivalent duration government bonds.

Why doesn’t the spread collapse? Nobody knows, but the spreads are generally small — 25-50bps — and one would need an exceptionally low cost of capital to arbitrage the spread between treasury bills and box spreads. Banks are arguably the lowest cost of capital market participants. Still, it is unclear if this would make sense for a bank to arbitrage because treasury bills will facilitate more leverage capacity relative to box spreads for a bank. And a bank’s return on equity is driven by leverage capacity. Another candidate might be huge market makers like Citadel or Susquehanna International Group. Still, even these operators have a cost of borrow that will likely be tied to fed funds plus 25-40bps. In short, as long as box spread “alpha” floats in the 25-50bp range, it is unlikely that any market participant would have the ability to arbitrage the spread on an after-cost basis. |

| ↑6 | via the Original Issue Discount (OID) calculation |

| ↑7 | Sec 1258 is often mentioned in the context of box spreads, however, this section generally does not apply to Sec 1256 contracts. If you are doing to DIY box spreads, all brokers we are familiar with report gains on box spreads as capital gains via 1099s. Obviously, we do not provide tax advice, and we strongly recommend you speak to a tax attorney to get a more detailed answer to complicated tax questions. |

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.