According to the Global Sustainable Investment Review 2023, more than $30 trillion is invested in sustainable investment strategies, as an increasing number of institutional and individual investors are incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into their portfolio construction process. The motivations for the increase in sustainable investing include:

- Investors desiring to express their personal values through their investments.

- The belief that incorporating ESG factors into portfolios leads to superior returns.

- The belief that tilting portfolios toward ‘green’ companies, and away from ‘brown’ or ‘sin’ companies reduces not only environmental risks but also risks of fraud (green companies have more robust risk controls), human rights scandals, consumer boycotts, regulatory risk, and lawsuits.

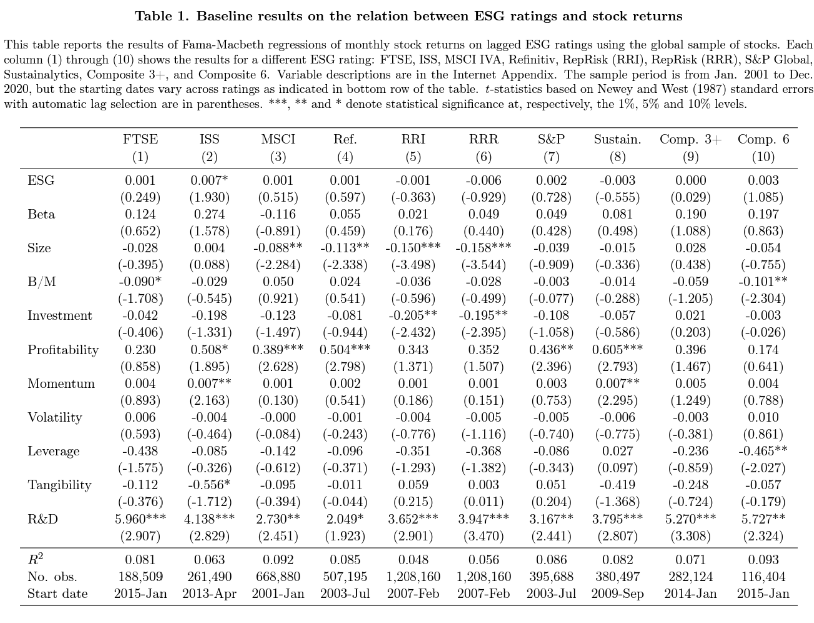

To determine the impact of sustainable investment strategies on equity returns, Romulo Alves, Philipp Krueger, and Mathijs van Dijk, authors of the December 2023 study “Drawing Up the Bill: Is ESG Related to Stock Returns Around the World?,” analyzed the relationship between ESG ratings and global stock returns. Their data sample, the most comprehensive to date, spanned the period 2001-2020 and covered 16,368 stocks in 48 countries and seven different ESG ratings providers. Controlling for an extensive set of stock-level control variables (market beta, size, book-to-market, investment, profitability, momentum, volatility, leverage, tangibility, and research and development), they found very little evidence that ESG ratings were related to global stock returns over the two-decade period. None of the ratings was statistically significant at the 5% confidence level, and only one was at the 10% level. In addition, the economic significance of the ESG coefficients was small. The authors explained: “The very weak statistical evidence is not just due to limited statistical power, but also due to the small ESG coefficient point estimates.” This finding held true across different regions, time periods, ESG (sub)ratings, and ESG momentum.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

The finding that there has been no effect conflicts with economic theory, which suggests that the screening out of certain assets based on investors’ tastes should lead to a return premium on the screened assets. Favored companies will have a lower cost of capital and thus a lower expected return to shareholders, while non-favored companies will have a higher cost of capital and thus a higher expected return to shareholders.

Their findings led Alves, Krueger, and van Dijk to conclude:

“Drawing up the bill of 20 years of ESG investing, our results indicate that ESG investment strategies have not systematically come at the expense of financial returns, and thus it has been possible to ‘do good without doing poorly.’ Our findings also suggest that the prices of strong ESG stocks have not consistently been driven up, and that, going forward, ESG investors could potentially still benefit from any demand effects resulting in the pricing of ESG preferences. On the flip side, our analysis implies that ESG investing has so far not been effective in reducing (increasing) the cost of equity capital of strong (poor) ESG firms, which could lead firms to internalize climate and social externalities.”

Findings Versus Economic Theory

Their finding that ESG ratings have no effect on global equity returns conflicts with some of the empirical research. Thus, caution is advised. In our book “Your Essential Guide to Sustainable Investing,” Sam Adams and I explained:

“Investor preferences lead to different short- and long-term impacts on asset prices and returns. Firms with high sustainable investing scores earn rising portfolio weights, leading to short-term capital gains for their stocks—realized returns rise temporarily. However, the long-term effect is that higher valuations reduce expected long-term returns. The result can be an increase in green asset returns even though brown assets earn higher expected returns.”

There can be an ambiguous relationship between carbon risk and returns in the short term. As the authors of the study “Carbon Risk” noted:

“Over time as the markets develop a better understanding of carbon risk and the unexpected component falls relative to the expected component, we should expect a positive relationship between returns and carbon risk.” Without this understanding, investors can misinterpret findings that appear to show a lack of a carbon premium. The reality might be that there was an ex-ante carbon premium, but the ex-post results showed no premium because of cash flows raising valuations of green companies.

In other words, the finding of no relationship might result from an offset between conflicting forces at work—the carbon premium we should expect has been offset by rising valuations of green stocks relative to brown stocks caused by the increase in cash flows to sustainable strategies. The effect of those cash flows on valuations has swamped the ex-ante carbon premium demanded by investors, and a new equilibrium has not yet been reached. Given the continued trend in sustainable investing, it may be a while before we get a new equilibrium. In the meantime, despite investors requiring a risk premium for carbon risks, green stocks could even outperform brown ones.

Larry Swedroe is the author or co-author of 18 books on investing, including his latest, Enrich Your Future: The Keys to Successful Investing.

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.