Earlier this month, McKinsey published a remarkable report on trends in global debt, and concludes that the world’s debt, rather than decreasing, is in fact increasing worldwide.

So much for deleveraging.

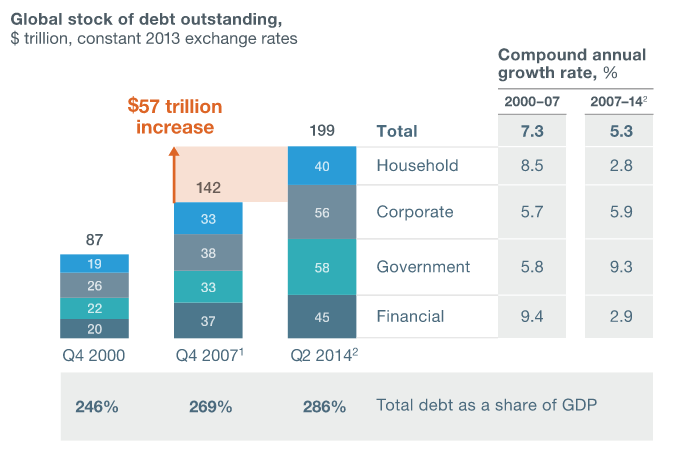

The report breaks down total debt into four broad categories:

- Household

- Corporate

- Government

- Financial

There is a lot to consider when it comes to global debt across these categories. For starters, leverage across all categories is growing globally, and in ways that pose a variety of risks to an integrated global economy:

Since the financial crisis in 2007, worldwide debt has increased both in absolute terms (by $57 trillion) and versus the GDPs of constituent countries (a 17% increase, to 286%), including in many developed economies. One frightening conclusion: Some countries may have reached a point where such debt levels are unsustainable. From the report:

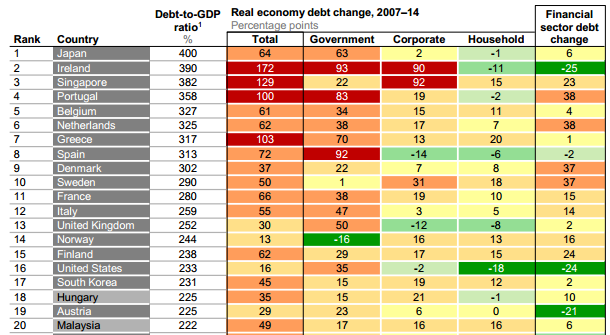

We find it unlikely that economies with total non-financial debt that is equivalent to three to four times GDP will grow their way out of excessive debt.

It is illuminating to consider these words in the context of the chart below, which shows the 20 most highly indebted nations as of 2Q14:

This would seem to suggest that several of the countries near the top of this list may face a day of reckoning in the foreseeable future. I was familiar with the problems in Japan, Greece, and Spain, but Singapore and Belgium? I hadn’t realized how serious the situation had become in these countries.

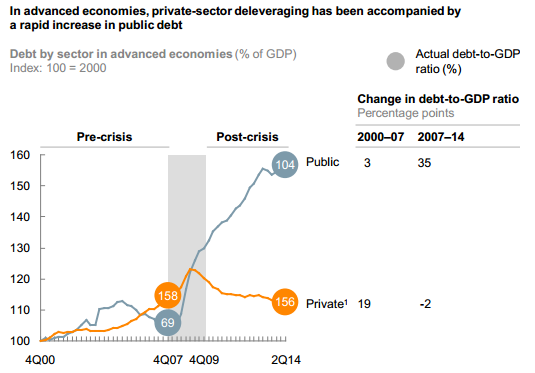

Also, per the chart above, here in the U.S., while household debt-to-income ratios, and financial-sector debt (notably in our shadow banking system) have declined, government debt in the U.S., and elsewhere, has exploded, as debt was shifted to government balance sheets during the bailout period during the crisis. Note in the chart below how relatively modest private sector deleveraging in developed economies has failed to offset dramatic increases in public debt:

Additionally, although the U.S. suffered a wave of defaults, which reduced household debt here at home, many developing economies continue to show high rates of growth in household debt, which accompanies hot real estate markets, particularly in highly populated urban areas. This dynamic underpinned the financial crisis and is a clear source of risk for many economies going forward, both advanced and emerging. Numerous countries, including Australia, Canada, Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, Malaysia, South Korea and Thailand, all have household debt levels that exceed peak, pre-crisis levels.

The McKinsey analysis also has some choice words for China, where total debt and household debt have both quadrupled since the crisis , and where the total debt/GDP ratio now exceeds that for the U.S. and for Germany, with leverage dangerously concentrated in the property sector (total debt increased from $7 trillion to $28 trillion). Approximately 45% of China’s debt is linked to real estate. From the report:

Property prices have risen by 60 percent since 2008 in 40 Chinese cities, and even more in Shanghai and Shenzhen. Residential real estate prices in prime locations in Shanghai are now only about 10 percent below those in Paris and New York.

In addition, China’s shadow banking system also now accounts for approximately 30% of total non-financial debt, with most financing going to the real estate sector. Also, the debt levels of many local governments appear unsustainable.

The good news? Chinese government debt remains at manageable levels. Also from the report:

China’s central government has the financial capacity to handle a financial crisis if one materializes—government debt is only 55 percent of GDP. Even if half of property-related loans defaulted and lost 80 percent of their value, we calculate that China’s government debt would rise to 79 percent of GDP to fund the financial-sector bailout.

(For curious readers, here is a post we did relating to the shadow banking system in the U.S., and here is one we did on the rise of credit in China.)

In sum, the global debt picture is complex and is arguably somewhat alarming. Historically, the creation of high levels of debt has led to financial crises, and today we simply have not seen the overall deleveraging hoped for in the wake of the financial crisis. In fact, we have seen the opposite at a global level.

What Are Some Solutions to the Problem?

McKinsey has some specific recommendations for the current situation. Some of these may provide a glimpse of our financial future:

Innovative Mortgage Contracts. We may see “shared responsibility” or “continuous workout” mortgages, in which mortgage payments are reduced when home prices fall, and lenders can share in capital gains when prices recover.

Private Sector Debts. Non-recourse loans, which are less common today outside of the U.S., could become more prevalent worldwide.

Macro Regulations. Limits on loan-to-value ratios, and on interest-only loans, combined with enhanced bank solvency requirements could reduce volatility of credit cycles.

Debt Tax Incentives. Deductibility of interest on debt could be modified, in order to increase the attractiveness of equity financing.

Sovereign Debt Workouts. Rather than highly disruptive outright defaults, we can modify governance, restructuring and monitoring methods to allow smoother resolution of high public debt.

Non-Bank Credit Sources. Global corporate bond markets are deepening, and functioning more effectively, and these will provide needed capital to the private sector, and take pressure off of banks.

See the McKinsey report for details and additional recommendations.

In the current environment, where substantive deleveraging is not occurring, it appears unlikely that traditional approaches to managing debt — growing out of the problem, or cutting spending — will be sufficient. Thus, we may need to be more creative. Perhaps this broader arsenal of sophisticated financial tools will allow us to better manage credit cycles and learn to live with debt.

About the Author: David Foulke

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.