Since we’ve released our new book, Quantitative Momentum, we’ve received a handful of basic questions related to momentum–specifically as it relates to stock selection. To address them, we’re writing an article about how to measure momentum.

How to measure momentum as it relates to stock picking

At this point, the so-called “momentum effect” has occupied academic researchers for several decades. Researchers have found that, on average, stocks with strong recent performance relative to other stocks in the cross section of returns tend to outperform in the future (see Levy 1967 for an old example and JT 1993 for a newer version). The effect has been well-documented by numerous follow-on researchers and the theory of “why” momentum works has been extensively explored (although we still don’t completely understand why it works).

So if an investor wants to harness momentum and implement it in the real world, a common question arises:

What is the best way to measure momentum for stock picking purposes?

The academic research response is to focus on so-called, “12_2 momentum,” which measures the total return to a stock over the past twelve months, but ignores the previous month. (e.g., Ken French data) But why use 12_2 momentum? Why shouldn’t we use the 3-month momentum, or the 6-month momentum?

Why 12-months? And why drop the most recent month’s returns?

Let’s take these questions one at a time.

Lookback Window

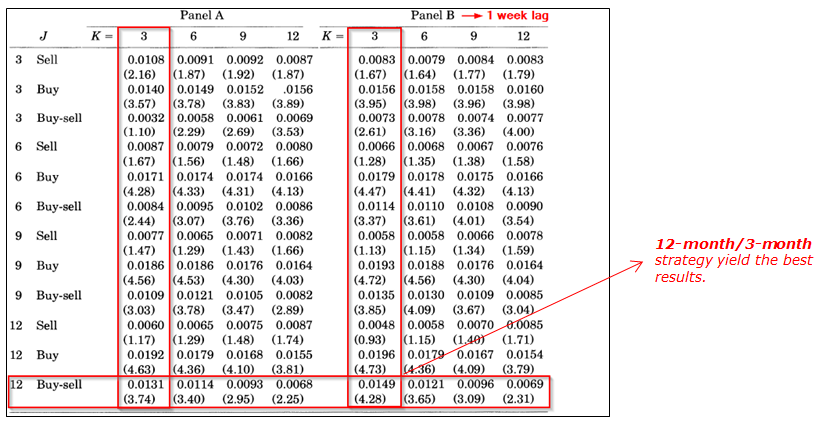

As we show in our blog about intermediate-term momentum, a few perturbations of how far back in time we should look have already been tested by academics. The chart below is from Jegadeesh and Titman in 1993. They show that the best performing strategy ranks stocks on their past 12-months returns, and holds for 3 months (forming overlapping portfolios).

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

Thus, 12-month momentum looks reasonable.

Why drop the most recent month?

Notice that we look at 12_2 momentum, not 12_1 momentum. But why skip the most recent month? The reason why relates to the short-term reversal effect associated with momentum.

There is an academic finding that short-term momentum actually has a reversal affect, whereby the previous winners (measured over the past month) do poorly the next month, while the previous losers (measured over the past month) do well the next month. We document the findings in this article about short-term return reversals.

Researchers often argue that this is due to microstructure issues. Thus, most academics ignore the previous month’s return (or week in the case of JT 1993) in the momentum calculation, and we also do this in order to eliminate this short-term reversal effect when implementing the strategy. It should be noted, however, that including the previous month’s returns has a marginal affect on the performance of momentum.

For more insight on 12_2 momentum, we invite you to explore a more important factor in momentum investing — rebalance frequency — as shown in the table above, and in our post about portfolio construction and momentum funds.

We hope you have found our exploration of how to measure momentum to be useful.

Good luck!

About the Author: Jack Vogel, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.