In 1921, University of Chicago Professor Frank Knight wrote the classic book “Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit.” An article from the Library of Economics and Liberty described Knight’s definitions of risk and uncertainty as follows:

Risk is present when future events occur with measurable probability. Uncertainty is present when the likelihood of future events is indefinite or incalculable.

In some cases, we know the odds of an event occurring with certainty. The classic example is that we can calculate the odds of rolling any particular number on a pair of dice. Because of demographic data, we can make a good estimate of the odds that a 65-year-old couple will have at least one spouse live beyond 90. We cannot know the odds precisely because there may be future advances in medical science, extending life expectancy. Conversely, new diseases may arise, shortening it. This illustrates the concept of risk. Compare that with examples of uncertainty: the odds of an oil embargo (1973), the odds of an event such as the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the odds of Iran blocking the straits of Hormuz, or the odds of a trade war with China. For investors, it is critical to understand the important difference between these two concepts—risk and uncertainty.

While investors much prefer to deal with risk, where they know the odds or can at least estimate them with a high degree of certainty, investing is generally much closer to uncertainty. And since there are no investment crystal balls, how should investors go about designing portfolios—what are the principles that should be followed?

One strategy is to hire active managers, those legendary gurus who can protect you from bad things happening to your portfolio. Unfortunately, the research, including the Eugene Fama and Kenneth French study, “Luck versus Skill in the Cross-Section of Mutual Fund Returns,” has found that fewer active managers (about 2 percent) are able to outperform their three-factor (market beta, size and value) model benchmark than would be expected by chance. And that is even before considering taxes. Adding to the bad news, there is no evidence that active managers add value in bear markets, just when they are needed most. That was the finding of a Vanguard study which appeared in the Spring/Summer 2009 issue of Vanguard Investment Perspectives. Defining a bear market as a loss of at least 10 percent, the study covered the period 1970-2008, which included seven bear markets in the U.S. and six in Europe. Once adjusting for risk (exposure to different asset classes), Vanguard reached the conclusion:

Whether an active manager is operating in a bear market, a bull market that precedes or follows it, or across longer-term market cycles, the combination of cost, security selection, and market-timing proves a difficult hurdle to overcome.

They also confirmed that “Past success in overcoming this hurdle does not ensure future success.” Vanguard was able to reach this conclusion despite the fact that the data was biased in favor of active managers because it contained survivorship bias. (For more on the challenges active investors face, read my December 2018 post.)

It is likely evidence such as this that led William Bernstein, author of “The Investor’s Manifesto,” to declare: “The reason that ‘guru’ is such a popular word is because ‘charlatan’ is so hard to spell.” Either that, or as Peter Drucker stated, “Charlatan is too long to use in a headline.” Even highly regarded mutual fund manager Ralph Wanger, in his book “A Zebra in Lion Country,” stated:

For professional investors like myself, a sense of humor is essential. We are very aware that we are competing not only against the market averages but also against one another. It’s an intense rivalry. We are each claiming that, ‘The stocks in my fund today will perform better than what you own in your fund.’ That implies we think we can predict the future, which is the occupation of charlatans. If you believe you or anyone else has a system that can predict the future of the stock market, the joke is on you.

The problem with active management is that the industry is focused on trying to manage returns—a losing proposition. So what’s the alternative? Perhaps it’s the strategy most likely to allow you to achieve your life and financial goals.

The Prudent Strategy in a World of Uncertainty

The prudent strategy is to focus not on managing returns, but on managing risk. How should an investor go about doing that? The following are the foundational premises of what I believe to be the most prudent approach to managing risk.

The first premise is to assume that markets, while not perfectly efficient, are highly efficient. Thus, after implementation costs, active management is a loser’s game, where the odds of winning are so poor that it’s not prudent to try. Just like the loser’s game of craps in Las Vegas, the surest way to win is to not play. In investing, not playing means using passive strategies that do not seek alpha, only beta (exposure to a factor or asset class, a unique source of risk and return).

If you believe that markets are highly efficient, you should also believe that all diversified sources of systematic risk (unique sources of risk and return), such as major asset classes and factor exposures like size, value, momentum, quality, profitability and carry should have the same expected risk-adjusted return. That leads to the conclusion that we should invest in strategies that broadly diversify across an entire asset class (or factor) instead of trying to determine which individual investments are likely to outperform. In other words, investors should be beta (unique sources of risk) seekers, not alpha seekers. That brings us to the third foundational premise.

Because diversification across unique sources of risk is a free lunch, providing a higher expected risk-adjusted return, the prudent strategy is to identify as many unique sources of risk and return as you can that meet the criteria you establish for investment. In “Your Complete Guide to Factor-Based Investing” my co-author, Andrew

- Persistent—It holds across long periods of time and different economic regimes.

- Pervasive—It holds across countries, regions, sectors and even asset classes.

- Robust—It holds for various definitions. For example, there is a value premium, whether it is measured by price-to-book, earnings, cash flow or sales.

- Investable—It holds up after considering trading and other costs.

The premium must have intuitive, logical, risk-based or behavioral-based explanations that provide the rationale for believing it should continue to exist. Investment factors that meet all the above criteria are market beta, size, value, momentum (both cross-sectional and time-series), profitability/quality and carry. Other investments that also meet all the criteria are the variance risk premium (VRP), which is the writing of puts and calls, reinsurance, and what is called “marketplace” or “alternative” lending (fully amortizing consumer, small business and student loans). Thus, each of these should be considered for inclusion in a portfolio. Note that exposures to factors can be obtained in either long-only or long-short portfolios. In the cases of reinsurance, marketplace lending and the VRP, exposures can be obtained through investing in what are called “interval” funds (funds that provide limited liquidity on a quarterly basis).

Summarizing, in a world of uncertainty, where there are no crystal balls allowing you to foresee the future, if you believe markets are efficient, you should believe that sources of systematic risk and return have similar expected risk-adjusted returns. And that should lead you to conclude that you should diversify across as many unique sources of risk and return as you can identify that meet all the established criteria. The problem is that the traditional 60% equity/40% bond portfolio has almost all its risk in one risk basket (market beta) and thus is not well diversified across unique sources of risk. Let’s see why this is the case.

Typical Portfolio: 60% Stocks/40% Bonds

Instead of thinking of exposures as percentages, we need to think about them in terms of how much risk is involved. While volatility is not the only type of risk (skewness, kurtosis and liquidity are other types of risk), it’s a good one. Thus, we will use it to calculate the amount of risk points each investment brings to the portfolio.

A typical well-diversified equity portfolio has a volatility of about 20 percent. Since equities have an allocation of 60 percent, they bring 1,200 (20 x 60) risk points to the portfolio. If we assume the 40 percent invested in bonds is in a five-year Treasury bond portfolio, it has a volatility of about 5 percent. Thus, the bonds bring 200 (40 x 5) risk points to the portfolio. The total number of risk points in the portfolio is 1,400, of which 1,200, or 86 percent, are in equities. Which raises the question: If we can identify other unique sources of risk, each of which has about the same expected risk-adjusted return as the stocks and safe bonds we are holding, why would we not want to include them, increasing the portfolio’s diversification and creating a more efficient portfolio? Why do we want to own a portfolio in which one risk factor—market beta—comprises almost 90 percent of the risk?

That brings us to the concept of a risk-parity portfolio. The risk-parity approach to portfolio construction seeks to allocate capital in a portfolio based on a risk-weighted basis. This approach attempts to avoid the risks and skewness of traditional portfolio diversification by considering the volatility of the assets included in the portfolio. In addition, the risk-parity portfolio is the most efficient portfolio when allocating to systematic assets and factors that have similar expected returns per unit of risk.

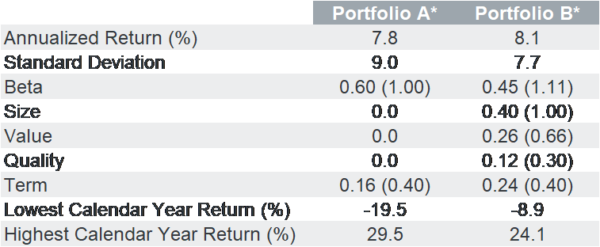

One way to approach risk parity is to increase exposure to equities with higher than market expected returns. For example, small value stocks have historically outperformed the market portfolio. Thus, owning more small value stocks than the market portfolio allows us to lower the portfolio’s exposure to market beta without lowering its expected return (because the stocks we own have a higher than market expected return). That lowers our exposure to market beta while increasing exposure to the size and value factors. In addition, the lower exposure to market beta allows us to hold more safe bonds, increasing our exposure to the term premium. These changes move us toward more of a risk-parity portfolio. Consider the following example of two hypothetical portfolios, A and B, that illustrate how to move a portfolio toward risk parity. The period is April 1993 through December 2018. The start date was chosen because it was the inception date of the DFA U.S. Small Cap Value Fund used in the example. I chose that fund because it has the longest record of any passively managed U.S. small value fund (the inception date of Vanguard U.S. Small-Cap Value Index Fund is April 1998).

- Portfolio A: 60% Vanguard Total (U.S.) Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX)/ 40% Vanguard Intermediate-Term Treasury Fund (VFITX)

- Portfolio B: 40% DFA U.S. Small Cap Value Fund (DFSVX)/60% Vanguard Intermediate-Term Treasury Fund (VFITX)

In the table below, note that Portfolio B is able to hold less equity exposure because the equity it owns has higher expected returns than the equity Portfolio A holds. The figures in the parentheses are the loadings (percent exposure) of each fund on a particular factor. We multiply that figure by the percentage allocation to determine the portfolio’s exposure to the factor. For example, Portfolio B has a 0.40 exposure to the size factor and the fund has a 40 percent allocation. (Data is from Portfolio Visualizer.)

Annualized return information is provided to show the benefits of factor diversification and does not reflect the actual performance of any portfolios managed by Advisor. Therefore, return information is hypothetical as it does not reflect the results of an actual portfolio managed by Advisor and does not reflect any advisory fees or the trading cost incurred in the management of an actual portfolio. Information from sources deemed reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Performance is historical and does not guarantee future results. April 1993 was selected as the starting date because of the start date of the mutual funds shown above. All portfolios rebalanced monthly.

Observations

- The two portfolios had similar returns and exhibited similar volatility.

- While Portfolio A had exposure to only two factors (beta and term), and its risk was dominated by the beta exposure, Portfolio B was more diversified across other factors, including greater exposure to the term premium. Thus, Portfolio B was more of a risk-parity portfolio.

- Portfolio B benefited from its greater diversification across factors. It produced a slightly higher return while exhibiting slightly lower volatility. In addition, it produced a much smaller worst-case annual loss, while its best annual gain was not that much smaller than Portfolio A’s.

Portfolios can be constructed to add exposures to other unique sources of risk, such as the ones mentioned earlier (carry, momentum, variance risk premium, reinsurance and others). By adding unique sources of risk and return that meet all the established criteria, we can improve the efficiency of a portfolio (that free lunch called diversification). Adding those unique sources of risk can improve the expected risk-adjusted returns by reducing the tail risks of the traditional 60/40 portfolio. And because almost all investors are risk averse, this is a worthy objective. It’s also important to note that, by improving the efficiency of a portfolio and cutting the tail risk, you improve the odds of not running out of financial assets—the primary objective of most investors. You see the benefits when running a Monte Carlo analysis.

It’s important to understand that, in order to benefit from diversification, you must accept the fact that your portfolio will likely underperform when the main component (such as the S&P 500 Index) of the less diversified portfolio is having a strong year (or decade).

Risk-Parity Portfolios

Because of the benefits it can provide, the concept of risk parity is an important one for investors to understand. And it should be at least considered as a starting point when designing a portfolio. However, it doesn’t have to be the goal or final result. The reason is that investors may not have an equal degree of confidence in each of the unique sources of risk. For example, I have more confidence in factors that have risk-based explanations than ones that have behavioral-based explanations. That doesn’t mean I don’t include at least some exposure to behavioral-based factors. The evidence is strong enough to convince me that some exposure is warranted. However, because of the greater confidence I have in risk-based factors, I have higher allocations to them. As an example, I have more weight on the size and value factors than I do on momentum; but I do include some exposure to both cross-sectional (relative) and time-series (absolute) momentum.

The bottom line is, the goal should be to achieve broad diversification across unique sources of risk. That said, risk parity is not the only way to achieve that goal.

1/N Portfolios

Victor DeMiguel, Lorenzo Garlappi and Raman Uppal, authors of the study “Optimal Versus Naive Diversification: How Inefficient is the 1/N Portfolio Strategy?”, which appeared in the May 2009 issue of The Review of Financial Studies, examined 14 different portfolio construction strategies (including mean variance and minimum variance) and found that naïve “1/N” portfolios (N being the number of unique sources of risk you have identified for investment) tend to be about as efficient as any other strategy (see Wes Gray’s article for an in-depth review). Thus, instead of trying to achieve risk parity, investors can simply build naïve 1/N portfolios that have equal allocations to many different unique sources of risk.

While 1/N might not be the “optimal” approach, as you increase N, you increase diversification and move closer to the optimal approach (recall that the traditional 60/40 portfolio, where N is just 2—market beta and term—has almost 90 percent of its risk in a single factor). 1/N also has the benefit of being simple: Like market cap weighting strategies, it requires no information whatsoever about the investments under consideration. For those interested in a full discussion of the alternative ways to optimize portfolio construction, I recommend the white paper “Portfolio Optimization: A General Framework for Portfolio Choice” as well as the follow-up paper “Revisiting the Portfolio Optimization Machine” by the team at ReSolve Asset Management.

The bottom line is that, when designing a portfolio, the main objective should be to diversify across as many unique sources of risk as you can identify that meet all the criteria you have established. Whether you choose to accomplish that objective via a risk-parity approach, a 1/N approach or some other approach isn’t as important as simply achieving broad diversification and then staying the course, remaining disciplined.

There is one more important point we need to cover. While there are still important diversification benefits from adding international equities, as the world becomes more integrated and technology benefits spread quickly, correlations among equity assets are rising, reducing the benefits of global diversification. In addition, in crises the correlation of all equity asset classes tends to rise toward one. The recognition of these two points increases the importance of adding other unique sources of risk and return to your portfolio in order to reduce the potential dispersion of returns (cut the tail risk).

Summary

By diversifying across unique sources of risk factors and alternative investments, we can create more efficient portfolios. We can reduce portfolio volatility and narrow the potential dispersion of returns, dramatically reducing the tail risk inherent in traditional 60/40 portfolios.

There is really nothing new here. Legendary hedge fund manager Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates has been using risk-parity strategies for decades. The endowments of Harvard and Yale have been incorporating unique sources of risk in their portfolios for decades. Fortunately, today’s individual investors now have access to such strategies without having to pay the traditional 2/20 fees of hedge funds, which leave the fund sponsors with all the benefits. Nor do investors have to pay the high fees of active managers. Many low-cost ETFs now provide access to the aforementioned factors. And the SEC’s approval of interval funds has allowed such companies as Stone Ridge Asset Management to create funds that provide individual investors access to the VRP (AVRPX), marketplace lending (LENDX) and reinsurance (SRRIX). (Full disclosure: My firm, Buckingham Strategic Wealth, recommends Stone Ridge funds in constructing client portfolios.)

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.