What Induces Children to Save (More)?

- Moritz Lukas (University of Hamburg) and Markus Nöth (University of Hamburg)

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category.

Introduction

The savings rate of US households has been declining substantially over the last decades. While they exceeded 10% in the 1970s and early 1980s, personal savings as a percentage of disposable personal income were lower than 4% in June 2017. This decrease affects all domains of household savings such as savings for education, the purchase of a home, medical and other emergencies, and, most critically, retirement. What Induces Children to Save (More)? , May 7, 2019

The AA blog has previously covered the education of adults with little to no financial literacy before and how financial education can guide them here. I have also covered the topic of getting children to be “money smart” on my own blog here. In this article, we look to expand on the framework of education and how it can be used to impact children’s attitudes toward savings as well as the characteristics in children that lead to a higher propensity toward saving.

The research in this paper was conducted with 246 elementary school students, ages six to eleven, in Bonn, Germany in their normal classroom environment. Gummy bears are used as the medium of consumption and deferred reward. Each student starts with ten gummy bears and is allowed to make consumption or savings decisions for each gummy bear thus they are not faced with an “all or none” decision.

What are the Research Questions

The authors investigate the following research questions through a savings experiment with children:

- Is savings behavior learnable and malleable among children?

- How will three of the most important savings interventions (below) among adults’ savings behavior affect the savings decisions of children, ages six to eleven?

- Interest Rates (Rewards)

- Time Horizons

- Default or Framing (Having to opt into savings -or-having to opt-out of savings)

- Do the following factors of heterogeneity reveal whether savings behavior is more likely to be learned or predetermined?

- Education (as measured by grade level)

- Familiarity with Money and Financial Constraints (as measured by whether a child receives an allowance and by the amount of their allowance relative to the median allowance amount of the group)

- Gender

- At what age do children begin to understand these interventions and adjust their decision-making? “Although these manipulations have been studied extensively with adults, their relevance for children’s decision-making is not yet well understood and there is no comprehensive evidence on the age at which the susceptibility to such manipulations starts to develop.”

What are the Academic Insights?

- Savings behavior is learnable and malleable to a certain extent.

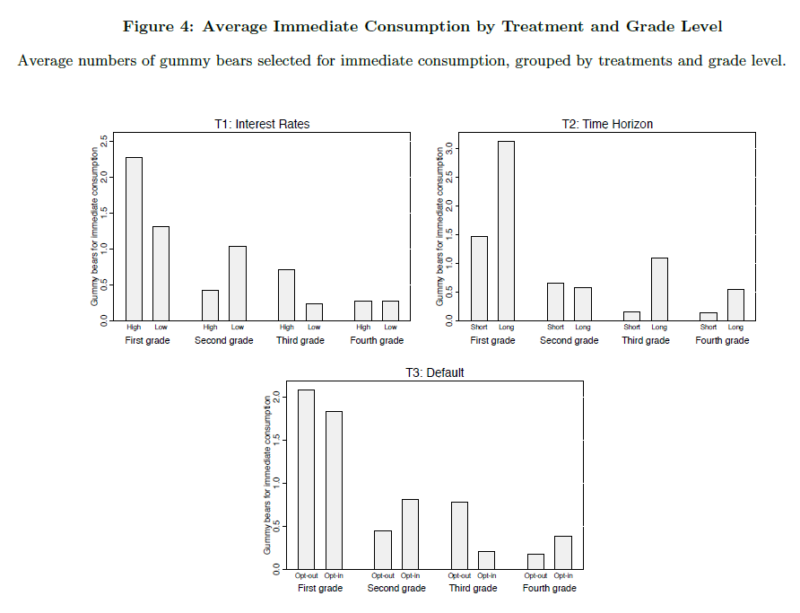

- Interest Rates (Rewards): Boys react more strongly to interest rates. Higher rewards = higher savings, lower rewards = lower savings.

- Time horizons: Boys react more strongly to time horizons. Because various traits observed during childhood are often found to persist, reflecting on time preferences and degrees of patience, “it might be possible to lay the foundations for reasonable savings decisions during childhood and adolescence.” Additionally, patience has the potential to influence success in other areas of life. This intervention was the most influential of the three (interest, default).

- Default: Girls more closely align with the default method of behavior, specifically saving less when they had to opt into savings and saving more when they had to opt-out of savings. This intervention was the least influential overall of the three.

- Children become more susceptible to savings rewards and time horizons around the age of eight based on third and fourth graders reacting strongly to the variation of rewards and time horizon.

- Familiarity with money and financial constraints tend to increase savings behavior.

Why does it matter?

Savings behavior can be a strong indicator of overall financial wellness and prudence. Despite lower savings rates, the responsibility for saving, especially for retirement, has shifted from employers to individuals (fewer pensions, more 401(k)’s). Combined with longer lifespans, low savings can present a problem in a household and society.

Because financial decision-making, including saving, needs improvement and can be learned to an extent at an early age, teaching children how to handle money is important in the home and in school. I recently wrote about our firm’s commitment to cultivating Money Smart Families. Because teaching children about money in schools is often discussed but inconsistently (at best) implemented, families need to recognize the need and teach children about money starting at an early age.

As stated by the authors:

Since intertemporal consumption behavior appears to be malleable during childhood, policymakers should carefully consider ways to exploit this malleability and educate young children and adolescents accordingly. Moreover, since some determinants of the susceptibility to policy measures are learned rather than predetermined, the formation of such traits could be actively supported. However, such policy measures need to account for heterogeneity; if heterogeneity is ignored, such measures will be effective for some individuals but ineffective for others.

The most important chart from the paper

Abstract

Based on an experiment with 246 elementary school pupils, we find that, similarly as for adults, lower interest rates, longer savings horizons, and opt-in defaults make children more likely to consume instead of saving; moreover, the amount of savings decreases with lower interest rates and longer time horizons. While boys react more strongly to interest rates and time horizons and girls react more strongly to defaults, children start to get susceptible to savings rewards and horizons around third grade, when they receive an allowance, and with a lower allowance; this suggests that savings behavior is learnable and malleable to a certain extent. Our findings shed new light on the development and malleability of traits related to intertemporal consumption.

About the Author: Anthony Saffer, CFP®

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.