Lingchi is the Chinese term for the form of torture we know as “death by 1000 cuts” that was reportedly used from 900 CE until it was banned in 1905. It is also translated as the slow process, the lingering death, or slow slicing “where a knife was used to methodically remove portions of the body over an extended period of time, eventually resulting in death.” (1)

In any industry, death by 1000 cuts is a strategy often employed by the incumbents to fend off smaller companies. The ETF industry is no different. As of this week, there are now two fewer cuts being applied to boutique ETF issuers:

- Commission-free trading for ALL ETFs (not just those that used to pay brokers to get on the “free shelf”)

- The new “ETF Rule” that was approved by the SEC.

In this post, I’ll give you some background on why these changes matter to the ETF industry, how much (or how little) those changes will affect things, and give deeper explanations on those topics. Before we get to those though, we need to set the stage so we’re all on the same page on the significance of these changes (2).

A Quick History of the ETF Industry

If death by 1000 cuts are minor things that add up to a single large thing, the ETF structure itself was the nuclear bomb to the asset management industry. Without it, who knows how many more decades some of the unscrupulous practices of the asset management industry would have gone on for. If you wanted to radically change the way business was done in the mutual fund industry, and had to start a mutual fund company to make those changes, it would’ve been nearly impossible to get the scale necessary to force the incumbents to change. But by introducing a better delivery structure (i.e., the ETF), new companies were able to enter the asset management business without the baggage of the legacy mutual fund companies.

Besides the Invesco acquisition of Oppenheimer Funds, it has been pretty quiet over the last 18 months since my last M&A post. That is, quiet in terms of fund companies buying or merging with other fund companies. It was anything but quiet in terms of the competition BETWEEN the ETF companies. The focus, however, has changed.

As I mentioned in previous posts, the ETF battle is essentially over. The players are set. This doesn’t mean I don’t(3) believe that a small ETF company could rise up to beat the incumbents over the next 25 years — that is plausible. However, what it means is that the behemoths in the mutual fund industry (who don’t have an ETF strategy) will disappear through mergers and acquisitions (e.g. Oppenheimer).

The Fee War is Over

Quick quiz: Who’s the low-cost leader in asset management? This is not a trick question.

What first came to your mind? Vanguard? Maybe you thought about Schwab? Hold that thought.

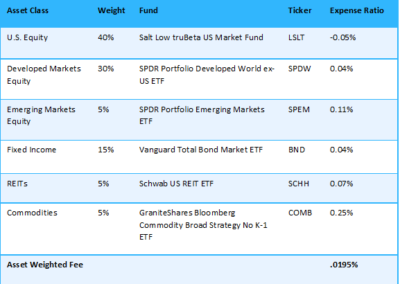

Here’s an idea I stole from Dave Nadig and Matt Hougan at ETF.com. It’s the “World’s Lowest Cost Portfolio.” Basically, take all the major asset classes, put in the lowest cost ETF for that category, and asset weight the expense ratio. In the original article from 2017, the world’s lowest-cost ETF portfolio was 0.05%.

Here’s my formulation for today’s lowest-cost ETF portfolio:

Thanks to having an ETF that PAYS YOU .05% to own it, you can now have a fully diversified portfolio of ETFs for 0.0195%, or less than 2 basis points!(4) That is as cheap a fee as the largest institutional money managers in the world could have ever dreamed to negotiate ten years ago for professional money management. And now it’s available to anyone. Crazy.

But what’s the real point to notice here? Only one Vanguard fund is listed. The firm most recognized as the low-cost leader is only the low-cost leader in one category. What’s the significance of that?

The largest asset managers in the ETF space have all come to the same conclusion: Broad-based, market-cap-weighted ETFs are simply a utility. There’s no edge there. At scale, these products can still make money, but for firms the size of BlackRock and JPM these products are more comparable to loss-leader type products in other industries.

Likewise, investors have moved on to at least consider other aspects of funds besides who is the absolute lowest cost in a category. This is shown by an example such as Franklin Templeton launching the lowest cost suite of country ETFs with little traction.(5). Or SoFi launching a free ETF with little traction even after moving their existing clients into it. There are plenty of other examples. Clearly though, there are other things investors are focusing on besides pure cost.(6)

That’s not to say it’s wrong to continue to apply pressure if you’re a competitor in ETFs and looking to attract investors. (Heck, we dropped our costs on our boutique focused factor products at the beginning of 2019.) That may still cause additional assets to flow to your fund vs your competitor. But for the investor, there’s no real difference between an expense ratio of 3 basis points and 2 basis points.

To summarize the situation:

- The ETF industry players are set

- The Fee War is over (for investors)

The ETF industry then is maturing and the strategic battles are narrowing. The first strategic front to win was simply to be in the ETF industry and build a solid business. If you did that, you did well as assets have flowed into the industry year after year. The second strategic front was on what type of ETF business to build. You could build for scale through the fee war or you could target a narrower audience with differentiated offerings. Now that the strategic battles have played out, the things that matter for firms in the ETF industry are becoming marginal and less influential to the asset management industry at large. However, commission-free trading and the ETF Rule changes are significant. Exactly how significant? Let’s take a look.

Big Issue #1: Commission-Free ETFs

Being small has its advantages. It has its disadvantages. The biggest advantages are the ability to move fast and be authentic. You have a flat hierarchy and flexibility. That’s why you see many smaller ETF issuers building brands in new mediums such as twitter. The big firms are slow to move into these new venues, as they need every tweet approved by a committee of PR “experts.” (7)

The biggest advantage large companies have is the advantage of cash. If you’re iShares or IBM or Pepsi, you WANT to pay for things. Not only do you want to pay for things, you are incentivized to pay as much as you can for things. Let’s use Pepsi as an example. They want the prime shelf space at the Grocery Store to be as expensive as possible for them to have their drinks displayed in the ideal spot. Right in the middle so it’s at eye level for you. Then their competitors (who can’t afford to pay for the prime shelf space) are put on the bottom shelf where you can’t see them, and you are less likely to buy them. We perceive top shelf things to be higher quality (whether they are or not).

It is the same system for the ETF industry. Before the commission cuts these past few weeks, many of the niche ETF issuers were stuck on the figurative “bottom shelf” at TD Ameritrade and Schwab. Even Vanguard was stuck on the bottom shelf as they refused to pay for the brokers to get their ETFs placed on the commission-free “top-shelf”.

Twelve months ago, Vanguard started to expose the industry practice of allowing some ETFs to trade commission-free by announcing they would be allowing all ETFs to trade commission-free on their brokerage platform. Big news, right? Pretty big. It put pressure on the other guys for sure. But why didn’t it receive the same reaction as when Interactive Brokers announced free trading and caused Schwab and TD Ameritrade to immediately follow up with their own announcements of commission-free ETF trading? For that, you have the fastest growing area of financial advisory to thank: The rise of the Independent Registered Investment Advisor (RIA).

Commission-Free Trading Means All ETFs Are On the Same Shelf

In order to understand why commission-free trading is such a big deal, we need to acknowledge the different brokerage offerings in the marketplace. First, all brokers help individuals buy and sell securities. However, not all brokers help investment advisors manage their business on their platform. For example, RobinHood is not in the RIA brokerage business. Vanguard is not in the RIA brokerage business. Schwab, TD Ameritrade and Interactive Brokers are in the RIA brokerage business.

With the independent RIA channel growing and the wirehouse channel shrinking (in terms of the number of advisors), RIA’s are looked at as the future of the financial advisory business. When Vanguard made the move to offer commission-free trading on all ETFs, it caused discussions at the other brokerage firms. But Schwab and TD Ameritrade could somewhat dismiss it as long as none of the other brokerage firms that offered RIA services made a move. When the Interactive Brokers press release went out announcing all ETFs would be commission-free on their platform it caused a domino effect of brokerage firms announcing they would now allow ETFs and stocks to trade commission-free on their platforms.

Now, for the majority of RIA’s out there, all ETFs are on the same shelf with no commission charges.

The reason this is so important is due to what Nassim Taleb refers to as the intolerant minority. In most cases, all it takes is 3-4% of a population to insist on doing things a certain way for the entire population to have to submit to their preferences. Taleb uses the following example:

Someone with a peanut allergy will not eat products that touch peanuts but a person without such allergy can eat items without peanut traces in them. Which explains why it is so hard to find peanuts on airplanes and why schools are peanut-free.

In the case of investor portfolios, some RIA clients will refuse to use ETFs that don’t have free commissions. The logic is unassailable — if my client is dropping $1000 in their account each month and I am paying a $5 commission for a 10 etf portfolio, the client pays a $50 commission to deploy $1000 — not a great deal!(8). In this case, all it took was a small minority of an RIA’s clients (individual investors) to insist on not paying commission fees on their ETF portfolios for the RIA to not include ANY non-commission free ETFs in their portfolios. If an ETF issuer wanted to get around this problem and have their ETFs included in the commission-free ETF programs the cost paid to the brokers was rumored to have cost a few hundred thousand per year per fund(!). This kept out many of the smaller ETF issuers (and Vanguard).

The combination of an intolerant minority and the huge upfront cost of the “commission-free” platforms made this a fairly significant hurdle for many ETF companies by making the rich companies richer and limiting the smaller players ability to gain traction. The removal of the small commissions to buy and sell ETFs will have a much larger effect for boutique ETF companies than it may appear. Can we quantify how big of a deal this is? Fortunately, we can.

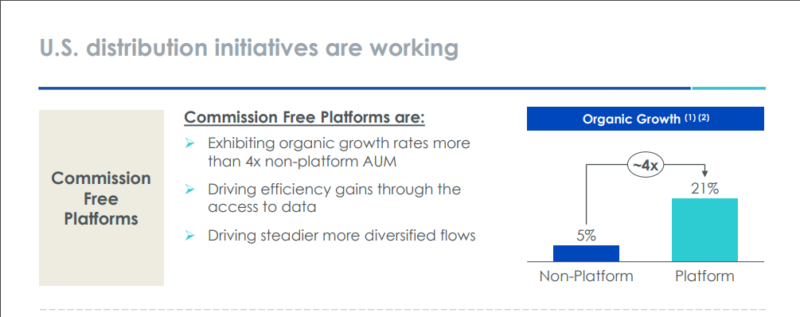

WisdomTree, the one pure-play ETF issuer out there that is publicly traded (and therefore can give us some insight on the inner workings of a company), reported in the second quarter that the ETFs they paid to have on commission-free platforms were selling at 4x(!) the amount of their non-commission free ETFs.

Here’s the chart from their second-quarter earnings call:

It will take years to determine exactly how big of a deal of this as the flows won’t change overnight. But that is a powerful comparison of the potential of leveling the competition.

Big Issue #2: The ETF Rule

This chart below by Bloomberg on their Bloomberg ETF IQ show did a great job of summarizing the important takeaways from the ETF rule, and others have done a great job going further into all the changes brought by the rule. No need to rehash all of that here.

I would like to add some commentary on the three major movements brought by the ETF rule:

- The rule does make it easier and less expensive to launch a brand-new ETF company…slightly. Keeping it a high level, the ETF rule will remove a regulatory requirement that used to cost brand new ETF issuers $10k-15k (minor compared to the overall cost of launching an ETF company, which is generally in the $1mm+ range) and the rule will save them a couple of months’ time to get their ETF to market. The money and time saved are helpful and a welcome change, but it is not going to be a major change for the industry at large.

- ETF companies must publish the spreads (the difference between what it costs to buy and sell) of their ETFs on their websites: This is slightly more impactful than number 1. Requiring ETF companies to publish the spreads on their funds will increase transparency and enable investors to (roughly) compare between ETFs what it will cost to transact in their funds. Most ETF issuers already provide this when a client requests it. The one negative is it may be a pain for some smaller ETF companies that don’t have the tech know-how to get this automated on their site and must pay additional money to get set up.

- The use of custom baskets, or non-pro-rata baskets, for active ETFs: This is the biggest change from the ETF rule and levels the playing field across ETF type and legacy ETF issuers (who often had different rules than newer ETF companies). Why is this important? In short, all ETFs can now take advantage of the tax-efficiency of the ETF wrapper, whereas certain parts were limited to a subset of companies before(9)

Conclusion

Since the launch of SPY in 1993, there’s been plenty of stories that we thought could be a big deal. In my time at the NYSE managing ETF listings, I had a few new ETF issuers tell me about how their idea “was going to change investing forever.” It is tough to cut through the noise sometimes and determine what is actually a big deal and what’s not. Commission-free ETF trading, however, is a big deal in leveling the competition in the ETF industry.

How will the changes affect the dynamics of the industry? No one in finance knows anything with absolute certainty. At times though, we are able to identify things that are definitely bad. Paying commissions charges to trade is definitely worse than not paying commission charges (all things equal). Regulation that adds no additional protection to investors but adds costs to ETF companies (and therefore investors) is bad. The commission-free changes remove a major hurdle in the competition amongst firms. The ETF Rule cleans up some messy parts of regulation. Combined, these are a few of the 1000 cuts the incumbents use to hold off the competition and it’s nice to have them removed. Only 990 or so to go! But as Steve Jobs said, “It’s better to be a pirate than to join the navy.”

References[+]

| ↑1 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | you can read my previous posts on the ETF industry if you want the more in-depth version of these next three paragraphs |

| ↑3 | double negative, I know |

| ↑4 | This is a marketing effort as the fund will be raised to a 27 basis point expense ratio once it achieves $100 million in AUM. But still crazy. |

| ↑5 | Their Japan ETF has over $200 million in AUM, but none of the others have cracked $70 million in AUM at the moment |

| ↑6 | e.g. trading volume, brand, customer service, etc |

| ↑7 | this excludes Cliff Asness, obviously. hah! |

| ↑8 | If you have a client that insists on paying you broker fees, please let me know! Maybe they are that in tune that they now want to avoid the payment for order flow and this could create a reverse “intolerant minority” situation on the other side. |

| ↑9 | Reach out if you want to learn more about the details of how this works. |

About the Author: Ryan Kirlin

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.