The collapse in interest rates, combined with historically high valuations (at least for U.S. stocks), have led many endowments, pension plans (especially those with large unfunded liabilities) and high net worth investors (such as those with their own family offices) to seek alternative investments that might offer more attractive returns. For example, over the 20-year period 1996 to 2016, pension plan allocations to private equity (PE) increased from just 3 percent to 11 percent, with the increase mostly coming at the expense of allocations to fixed income.

The term “private equity” is used to describe various types (e.g., buyout funds and venture capital funds) of privately-placed (non-publicly traded) investments. Even though buyout (BO) funds and venture capital (VC) funds have a similar organizational form and compensation structure, they are distinguished by the types of investments they make and the way those investments are financed. BO funds generally acquire 100 percent of the target firm (which can be public or private) and use leverage. VC funds take minority positions in private businesses and do not use debt financing.

In their 2019 whitepaper “Demystifying Illiquid Assets: Expected Returns for Private Equity,” the research team at AQR Capital began their analysis by noting that “the challenge is that modeling private equity is not straightforward due to a lack of good quality data and artificially smooth returns.” They attempted to bring clarity by considering theoretical arguments, historical average returns, and forward-looking analysis.

AQR analyzed whether private equity’s realized and estimated expected return provided superior risk-adjusted returns over lower-cost, more highly diversified, and highly liquid public equity counterparts. In other words, is all the hype and hope justified? Their study covered the period from July 1986 through December 2017. Following is a summary of their findings:

- The market beta of PE has been more than 1 (about 1.2), indicating it has about 20 percent more risk than the market. In addition, PE tends to invest in small and value stocks, which have also historically provided above-market returns. Thus, the overall market, or the S&P 500 Index, is not a good benchmark. And that is without considering their illiquidity.

- PE outperformed the S&P 500 Index by 3.4 percent in annualized returns. But when compared to a 1.2x leveraged small-cap index, this falls to just 0.7 percent (not much of an illiquidity premium). And PE outperformed a basket of unleveraged small-cap value stocks by just a compound 0.4 percent per annum.

- There has been a decreasing trend over time in both expected and realized returns, which has not slowed the institutional demand for private equity.

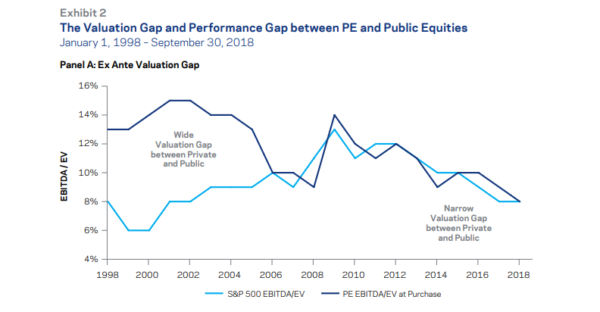

- Using earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization-to-enterprise value (EBITDA/EV) as their metric for expected returns, the ex-ante return premium for private equity fell from about 5 percent at the start of the period to zero by 2006—and has lingered around zero ever since. The narrowing gap reflects the demand by investors: As PE has grown relatively richer and the valuation gap has narrowed, PE’s outperformance over public equities has declined, with realized outperformance for post-2006 vintages dropping to virtually zero, even before adjusting for size and leverage.

The research team at AQR noted that many academic studies have found that “PE fund returns tend to be lower after ‘hot-vintage’ years characterized by high fundraising activity or capital deployment, attractive financing conditions, and easy leverage. Skeptics stress that the current environment can be characterized by low financing rates coupled with increasing institutional demand for PE, more PE firms, record-high dry powder (committed uncalled capital), and competition from cash-rich public companies and sovereign wealth funds. Thus, PE faces headwinds that make it less likely to deliver the strong returns it has in the past.” They added that richness versus history is not unique to PE. Many other asset classes appear expensive today, perhaps reflecting the easy global monetary policies of the 2010s.

In their study “Have Private Equity Returns Really Declined?” published in the Fall 2019 issue of The Journal of Private Equity, Gregory Brown and Steven Kaplan noted that EBITDA multiples averaged 10.9 in 2017 and 2018. That’s higher than any other period, including the late 1990s.

Explaining Increased Demand in the Face of Poor Risk-Adjusted Returns

AQR’s team hypothesized that the increased demand in the face of lowered returns is due to investors’ preference for the “return smoothing” properties of illiquid assets. Unfortunately, the smoother returns are illusory. For example, in his 2017 study “Replicating Private Equity with Value Investing, Homemade Leverage, and Hold-to-Maturity Accounting, Erik Stafford found that the reported volatility of the PE indexes is considerably lower (about half) than those of the aggregate market (about 9 percent versus 17 percent) and the replicating portfolio of levered selected stocks (21-22 percent). That is illogical (it cannot be the case), especially since the private equity firms have much higher betas than the market and use much more leverage than typical public companies. The lower reported volatility results from the lack of daily mark-to-market accounting, long holding periods and the considerable flexibility PE has in determining valuations. In other words, return smoothing creates the illusion of less risk. It also creates the illusion of PE having low correlations to equity markets as well as the illusion of alpha if measured on a naïve basis. Note that Stafford also found that the long-run average excess returns of PE over public equity can be matched by a leveraged, small-cap value strategy. David Foulke and Wes Gray previously covered this in blog posts here and here. Thus, it appears that the PE industry, on average, has offered scant illiquidity premium beyond these typical factor tilts, all while collecting large fees—close to 6 percent.

Unfortunately, despite the evidence of little more than perhaps a scant premium, AQR noted: “In contrast to our conservative forecasts, institutional investors widely expect PE to outperform public equity by 2-3%.” They added: “This may be due to the inherent difficulty of modeling illiquid assets, and lack of transparency on fees and performance.” Perhaps. The field of behavioral finance provides us with another explanation for the demand for PE, despite the findings of poor risk-adjusted returns.

Behavioral Explanation for the Demand for PE

In an interview with AAII, Meir Statman, a leader in the field of behavioral finance, provided us with another explanation:

“Investments are like jobs, and their benefits extend beyond money. Investments express parts of our identity, whether that of a trader, a gold accumulator, or a fan of hedge funds. We may not admit it, and we may not even know it, but our actions show that we are willing to pay money for the investment game. This is money we pay in trading commissions, mutual fund fees, and software that promises to tell us where the stock market is headed.” Meir Statman, Interview with AAII

He went on to explain that some invest in hedge funds for the same reason they buy a Rolex or carry a Gucci bag with an oversized logo—they are expressions of status, available only to the wealthy. Just substitute PE for hedge funds and you have an explanation for the demand for PE investments.

PE offers what Statman called “the expressive benefits of status and sophistication, and the emotional benefits of pride and respect”—they’re ego-driven investments, with demand fueled by the desire to be a “member of the club.” With that in mind, investors in PE (and hedge funds) would be well served to consider the following from another leader in the field of human behavior, Groucho Marx: “I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member.”

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.