It has been well documented both that stock returns have much fatter tails than a normal distribution would generate, and that tail events occur much more frequently than a normal curve would predict.(1) For example, Benoit Mandelbroit and Richard Hudson examined the daily index movements of the Dow Jones Industrial Index from 1916 to 2003. They noted that if stock returns were normally distributed, a single-day price move of more than 3.4 percent would have occurred 58 times. The actual number of occurrences was 1,001, more than 17 times as frequently. They found that a daily price move of more than 4.5 percent would have occurred just six times, yet it occurred 366 times, or 61 times greater than with a normal distribution. They also found that a daily price move of more than 7 percent would have occurred just once in every 300,000 years. Yet, it had occurred 48 times! In other words, markets are risky and returns exhibit excess kurtosis (the tails are much greater than would be expected if returns were normally distributed). The risk of large losses combined with the high-risk aversion of most investors provides us with a logical answer for why stocks as an asset class have provided such a large risk premium—investors demand a large premium to bear risks they dislike.

Supporting evidence for a large tail risk premium was provided by Fousseni Chabi-Yo, Stefan Ruenzi, and Florian Weigert, authors of the study “Crash Sensitivity and the Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns,” which was published in the June 2018 issue of the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. They demonstrated that U.S. stocks that are likely to perform badly during market crashes earn significantly higher average returns than stocks that offer protection against market downturns. And Bryan Kelly and Hao Jiang, authors of the 2014 study “Tail Risk and Asset Prices” found that “cross-sectionally, stocks with high loadings on past tail risk earn an annual three-factor alpha 5.4% higher than stocks with low tail risk loadings.”

Clearly, understanding the dynamics of tail risk and its relation to asset returns is of crucial importance in investment decision making and has implications for portfolio management.

Sofiane Aboura and Y. Eser Arisoy contributes to the literature with their study “Can tail risk explain size, book-to-market, momentum, and idiosyncratic volatility anomalies?” published in the October/November 2019 issue of the Journal of Business, Finance & Accounting. They sought to determine whether tail risk helps explain the performance of size (small stocks), book-to-market ratio (value stocks), momentum, and idiosyncratic volatility (IVOL) sorted portfolios. They used a measure of tail risk (TAIL) developed by Bryan Kelly and Hao Jiang, authors of the aforementioned 2014 study “Tail Risk and Asset Prices.” Their hypothesis was that tail risk-averse investors view stocks with negative (positive) exposure to aggregate tail risk as riskier (less risky), because they are expected to lose more (less) in periods of tail events. Thus, stocks with negative (positive) sensitivity to aggregate tail risk should command a higher (lower) risk premium. Aboura and Arisoy’s study covered the period 1963 through 2013.

The following is a summary of their findings:

- Tail risk is time-varying. It’s countercyclical and strongly related to good and bad states of the economy.

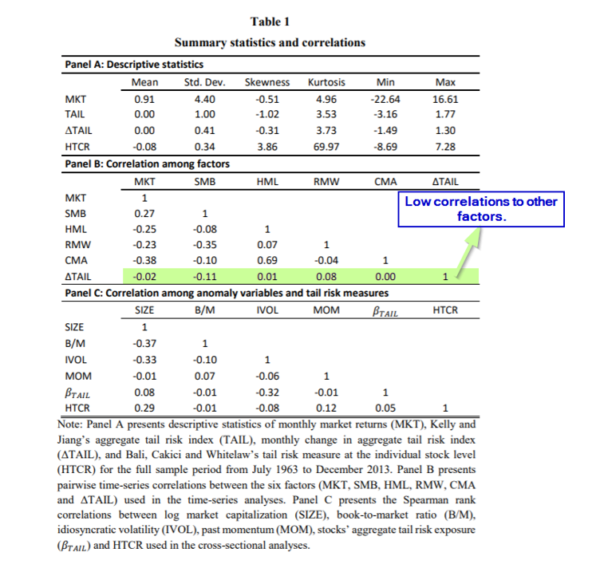

- The tail risk factor was not correlated with the five Fama-French factors (beta, size, value, investment, and profitability) used in their augmented six-factor model, and the six-factor model explains the cross-section of 25 portfolios (5×5) better than the five-factor model.

- Portfolios that contain small, value, high idiosyncratic volatility, and low momentum stocks exhibit negative and statistically significant tail risk betas. In particular, small stocks are far more negatively exposed to tail risk than large stocks.

- Tail risk helps in explaining the four pricing anomalies, particularly the size, and idiosyncratic volatility anomalies—explaining virtually half of the IVOL premium and almost two-thirds of the size premium.

- Extreme size portfolios (containing the smallest and biggest stocks) are more negatively exposed to aggregate tail risk than mid-cap stocks. In particular, the portfolio of small stocks and the arbitrage portfolio that is long in the quintile of smallest stocks and short in the quintile of biggest stocks (Lo-Hi MCAP) exhibit a negative and statistically significant aggregate tail risk exposure, which is much higher in magnitude compared to any other portfolio.

- The portfolio of value stocks and the arbitrage portfolio that goes long the quintile of highest B/M stocks and short the quintile of lowest B/M stocks (Hi-Lo B/M) are negatively and significantly exposed to aggregate tail risk.

- The portfolio of stocks with high idiosyncratic volatility and the arbitrage portfolio that is long in high IVOL stocks and short in low IVOL stocks (Hi-Lo IVOL) also exhibit negative and significant aggregate tail risk loadings—due to their strong negative exposure to aggregate tail risk, high idiosyncratic volatility stocks should be considered riskier at times of increased tail risk. This explains why high idiosyncratic volatility stocks lose more during bad states of the economy.

- The portfolio of low-momentum stocks exhibits a negative and statistically significant aggregate tail risk exposure, and that the arbitrage portfolio that is long in high MOM stocks and short in low MOM stocks (Hi-Lo MOM) exhibit a positive and significant aggregate tail risk loading— due to their strong negative exposure to aggregate tail risk, low momentum stocks should be considered riskier at times of increased tail risk.

- “The results obtained for the whole sample are mainly driven by the subsample characterizing bad states of the economy, in which portfolios containing small, value, high idiosyncratic volatility, and low momentum stocks exhibit significantly higher exposures.”

Summary

Tail risk is an important determinant of asset prices. As a result, crash-sensitive stocks command a risk premium. Thus, tail risk provides a risk-based explanation for the size and value premiums. Their findings led Aboura and Arisoy to conclude that,

investors are much more averse to holding small, value, high idiosyncratic volatility, and low momentum stocks due to their increased aggregate tail risk exposures and corresponding losses in times of market distress. Therefore, tail risk averse investors will consider such stocks as riskier and will demand compensation for including them in their portfolios.

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.