Global Factor Premiums

- Baltussen, Swinkels, Vliet

- Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Here are the slides tied to the paper.

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category

What are the Research Questions?

Interest in factor investing was hot several years back but seems to have died on the back of poor relative performance and a move to hotter products in thematics and ESG. But, for better or worse, we haven’t moved on. We are boring and we trust the process. We still believe that markets do a decent job at pricing risks and rewards, but they aren’t perfect. There is a bunch of noise caused by these pesky humans, which are driven by fear and greed behaviors that create systematic mispricing opportunities that are neither cheap and/or easy to exploit. Factor portfolios seem to be an efficient way of capturing the various risk/returns available in the market. And the reality is investing is not a pure science — there’s some art involved as well.

But not everyone agrees that factors are the way to go, nor should they.(1)

The factor debates could fill a library with journal articles (or a blog with over a 1,000 posts, like our own!). In my mind, one of the biggest frictions to understanding factors is getting everyone to agree on the baseline facts. I think this recent paper (which is being published in the JFE, a top-flight “A-pub” journal) from the team at Robeco does a great job establishing the baseline facts regarding factors over the ultra-long-term. We can still argue if past performance will predict future performance, but at least this paper helps establish a baseline on “what is the past performance?”

This paper also has me questioning the “risk vs. mispricing” debates. Prior to reading this I was in the “equal-weight” camp — premiums are likely due to some fundamental risk and a healthy dose of mispricing that is tough to exploit. But now I’m shifting more towards, “Maybe emotional humans plus arbitrage frictions are everything.”

After reading this paper a few times — and reviewing the internet appendix (authors hooked me up) — I am in awe of this paper and the work required to make this happen. What an effort. We commend the authors for sharing this incredible paper.

Here are the core research questions the authors ask:

- Do factors hold up over the full sample period?

- Do factors hold up in the ‘out of sample’ period?

- Can factors be explained via “rational” economic risks?

What are the Academic Insights?

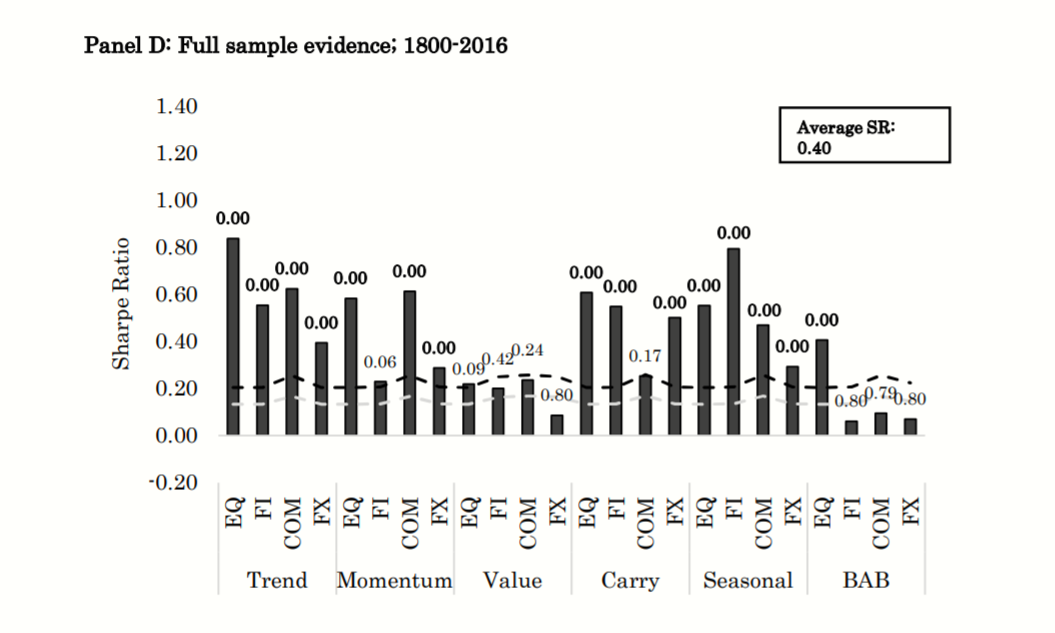

The authors look at factors over the 1800 to 2016 time period.(2) The authors focus on exploring 6 core factors that we all know and love: time-series momentum (i.e. trend-following), cross-sectional momentum (i.e., momentum or relative strength), value, carry, return seasonality, and betting against beta (i.e., low vol). Next, they examine these factors in the context of 4 asset classes : stocks, bonds, commodities, and currency. In total, the authors explore 24 factor premiums across the different factors and markets.

- YES. Factors work over the full sample. The authors examine the 24 core factor premiums across the entire time period and find that they are generally robust, which isn’t too surprising since a large part of the sample is “in-sample” and well understood.

- YES. The authors leverage newer empirical techniques that seek to mitigate the problems with data-mining (discussed here in “Take that Alpha and shove it“). On net, the out of sample exploration of factors is pretty consistent with the evidence we all know and love. The few exceptions are “value” in the context of FX and the BAB effect outside of stocks (i.e., not robust in bonds, commodities or FX).

- Not really. The authors explore a sample with 43 bear market years and 74 recession years, multiple wars, depressions, and so forth. Surprisingly, the authors find the following:

Across several tests we find no supporting evidence for these explanations, with global return factors bearing basically no relationship to market, downside or macroeconomic risks.

As a former Eugene Fama student that endured years of successful brainwashing in the ways of EMH (but was never completely sold!), this statement is a bit hard to digest. I’ll need to chew on it a bit more and read the paper a few more times.

Why does it matter?

This paper does a great job of outlining the baseline facts regarding the long-term evidence on factors across time and asset classes. The fact that factors ‘work’, in general, is not altogether surprising. We would already expect factors to work if our baseline hypothesis is that markets were reasonably efficient at pricing pains and gains over time. However, where this paper has me thinking is in the “why do factors work” sections. My prior is that factor portfolios capture elements of fundamental risks and mispricing that is difficult and painful to exploit. The authors suggest that maybe factors don’t proxy for fundamental risk at all. That is a surprising finding.

The Most Important Chart from the Paper:

Abstract

We examine 24 global factor premiums across equity, bond, commodity and currency markets via replication and out-of-sample evidence between 1800 and 2016. Replication yields ambiguous evidence within a unified testing framework that accounts for p-hacking. Out-of-sample tests reveal strong and robust presence of the large majority of global factor premiums, with limited out-of-sample decay of the premiums. We find global factor premiums to be generally unrelated to market, downside, or macroeconomic risks in the 217 years of data. These results reveal significant global factor premiums that present a challenge to traditional asset pricing theories.

References[+]

| ↑1 | The bayesian analysis makes this more clear in the context of replication studies. From the paper: “These results imply that one does not need to be very skeptical to disregard the empirical evidence.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Is the data perfect? Of course not. We’ve played with the data sources and they can be dirty, nasty, and ugly. But that is the reality of research and the potential benefit of exploring new data is new insights. |

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.