Since the development of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) about 50 years ago, academic researchers have documented hundreds of “anomalies” that generate significant positive alpha. There are now so many that economist John Cochrane, in his 2011 presidential address to the American Finance Association, referred to them as the “factor zoo,” which I hit on in my post “Is there a Replication Crisis in Finance?” There are certainly incentives to find anomalies, both for academia and investment firms, raising concerns that many of them may be nothing more than the result of data mining exercises, or they rely too heavily on tiny stocks to be exploitable. Concerns can be mitigated by out-of-sample tests in non-U.S. markets as well as having intuitively strong risk- or behavioral-based explanations (along with limits to arbitrage) for the existence of an anomaly.

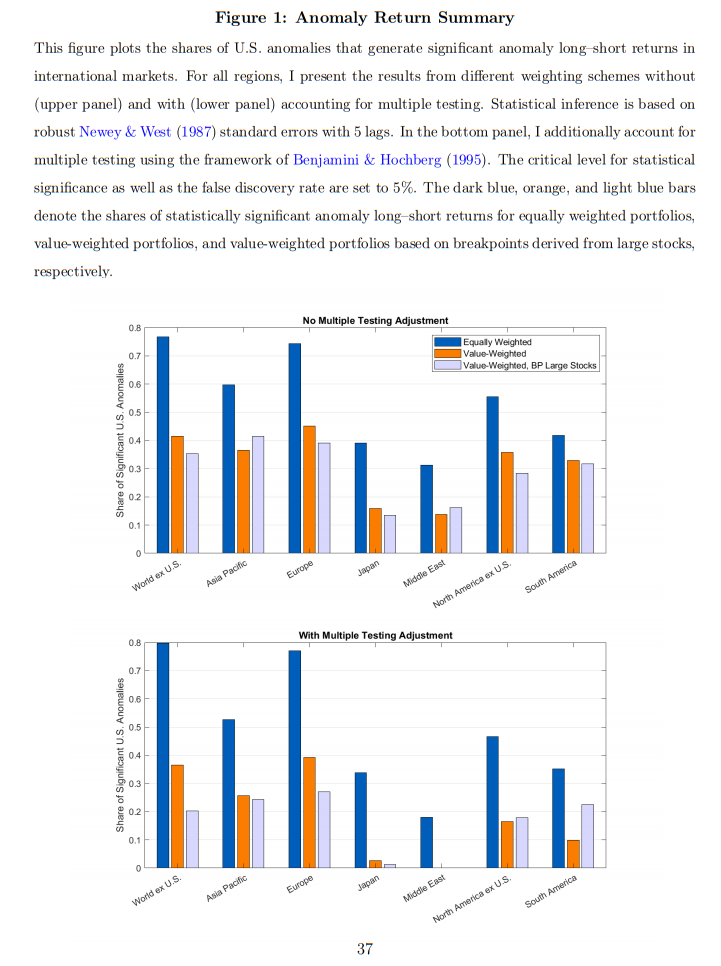

Fabian Hollstein contributes to the anomaly literature with his September 2020 study “The World of Anomalies: Smaller Than We Think?” Hollstein examined 132 return anomalies in international equity markets. His data set included all (47) countries classified as developed and emerging markets by Morgan Stanley Capital International. For each region and anomaly variable, he sorted the stocks into equal-weighted decile portfolios, value-weighted decile portfolios, and value-weighted decile portfolios using breakpoints derived from large stocks (mitigating the effect of microcaps). The holding period for the anomalies was generally one month, repeating the sorting at the end of each month. The data spanned the period January 1990 to December 2017.

Following is a summary of his findings:

- For the entire world market, 74 anomalies yielded a statistically significant long-short return for equal-weighted portfolios—56 percent of the anomalies replicated in international data based on this weighting scheme. The average absolute annualized anomaly long-short return was 6.5 percent.

- The number of significant long-short returns shrank to 40 (30 percent) for the value-weighted portfolios. The average absolute annualized anomaly long-short return also shrank compared to equal-weighted portfolios, from 6.5 percent to 5.2 percent.

- Only a few anomalies replicated when mitigating the impact of tiny stocks, accounting for multiple testing (multiple comparisons arise when a statistical analysis involves multiple, simultaneous statistical tests, each of which has a potential to produce a “discovery” of the same data set or dependent data sets; a stated confidence level generally applies only to each test considered individually, but often it is desirable to have a confidence level for the whole family of simultaneous tests) and using prominent factor models to adjust for expected returns. Accounting for the impact of tiny stocks and multiple testing, only 19 of 132 anomalies (14 percent) yielded significant long-short returns in the ex-U.S. world cross-section.

- A few anomalies were strong across regions. Most of these were value anomalies (such as price-to-book, price-to-cash flow, and price-to-earnings). Others included gross profitability, earnings surprise, and new shares issuance.

- The Fama-French size factor (SMB) and the Pastor and Stambaugh liquidity factor do not survive international tests.

- Moving from equal-weighted portfolios to value-weighted portfolios with breakpoints derived from big stocks cut the number of significant anomalies in half for most regions—important because the stocks in international markets are on average considerably smaller than those in the U.S.

- Prominent factor models, including Stambaugh and Yuan’s mispricing (anomaly)-based model, shrank the anomaly universe. The best-performing models contained factors related to investment and profitability in addition to the long-established risk factors (beta, size, and value).

- For the individual regions, the share of anomalies that did not survive even the single-testing framework (using only equal weighting) was also very large. It was 80 percent for Europe, 92 percent for Japan, 88 percent for the Middle East, and 81 percent for North America. For the Asia Pacific and South America, which both consist mostly of emerging markets, the shares were 65 percent and 75 percent, respectively.

His findings led Hollstein to conclude that:

“Most of the anomalies reflect random deviations from market efficiency.”

He added:

“Overall, my results indicate that an overwhelming majority of previously documented anomalies are illusory and cannot be profitably traded upon in international markets.”

Hollstein’s findings add to the body of research demonstrating that investors should be skeptical of findings of anomalies. To address the skepticism and minimize the risks of data mining, in our book, Your Complete Guide to Factor-Based Investing, Andrew Berkin and I provide the following criteria a factor should show evidence of before investing: a premium that is persistent across long periods of time and economic regimes; pervasive across the globe, industries and even asset classes; robust to various definitions; survives transactions costs; and has intuitive risk-based or behavioral-based explanations for why that premium should be expected to persist. The equity factors that met our criteria are beta, size, value, momentum, and profitability/quality. I do recommend that the size factor be screened for quality, avoiding lottery-like stocks.

Important Disclosure:

The information in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal or tax advice. The analysis contained herein is based upon third party information and may become outdated or superseded at any time without notice. Third-party information is deemed to be reliable but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge it is solely at your convenience and does not necessarily imply any affiliation, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Stategic Wealth®. R-20-1482

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.