Do you trust your doctor?

If you’re like most people, chances are good that you do. And why not? What do you know about medicine anyway?

But who do you trust when it comes to your money?

In “Money Doctors Or Self-Medication? Equity Portfolio Delegation During Stock Market Crises,” By Daniel Dorn and Martin Weber (a copy is here), the authors explore how trust in professional investment managers affects investors’ willingness to take risk in the stock market. As an aside, Daniel Dorn happens to be a trustee of our ETF Trust, so we’re big fans of him and his work.

Before we get into this paper, some background is required. Back in March, Jack wrote up a separate but related 2015 paper called, “Money Doctors,” by Gennaioli, Shleifer, and Vishny.

A quick summary of the “money doctor” concept

The basic idea of the Gennaioli at al. “Money Doctors” paper is that people trust portfolio managers in much the same way they trust doctors.

When it comes to medical issues, people generally feel they lack the necessary skills to make health care choices independently. That makes sense. What if you skip the doctor and opt for an aspirin rather than gall bladder surgery? Potential bad outcomes are scary.

Similarly, in investing, people may be unfamiliar with financial topics, and are thus fearful of taking risk without relying on a money manager, who might give them confidence based on perceived manager attributes such as training and experience. You might also trust them based on a fancy suit or impressive advertising.

The original money doctor paper focuses on the idea that, regardless of the quality of advice investors actually receive, investors’ perception of risk changes based on their trust in the advisor. For some, in order to invest in the stock market at all, they might need someone to hold their hand.

But just because you trust someone today, it does not follow that you will necessarily trust them tomorrow. Turning back to medicine for a moment, what if your doctor has told you for years everything is fine, but then you suddenly experience a heart attack? “Why didn’t you warn me about this?!” you might cry. Maybe the doctor should have known, or maybe not. Regardless, your trust in the doctor could very well go out the window.

Testing the money doctor concept

In the Dorn/Weber paper discussed today, the authors investigate the money doctor concept and conduct an ingenioius analysis that attempts to measure what happens to trust in money doctors when it is tested in a financial crisis, which might be the financial equivalent of a heart attack.

First, they examine a baseline assumption of the money doctor idea. For those investors who require the assistance of money managers as a necessary condition for taking risk and investing in the stock market, they will delegate financial decision-making by allocating to actively managed stock funds (rather than to passive funds or individual equities). They trust these fund manager/money doctors will keep them safe. Otherwise, they simply wouldn’t invest.

Next, the authors wanted to test a hypothesis. If it is true that these investors require a trusted active fund manager in order to take risk and invest in stocks, what happens during a financial crisis? If these investors lost trust in their money doctors, they might take extreme action in a crisis – like by selling all their equity positions.

What does the evidence say?

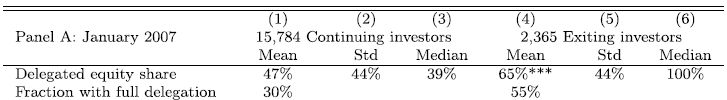

The authors looked at a sample of 40,000 self-directed brokerage customers from 1/07 through 10/11 at a German bank. Note that this period brackets the 08 financial crisis. The panel below shows results for “Continuing investors,” who held equities throughout the period, and “Exiting investors,” who sold all of their equity positions during the period. “Delegated equity share” is the percentage of equities held in actively managed funds. Here are summary results:

A few things to note. First, at the beginning of the sample in 07, as depicted above, “Exiting investors” who subsequently sold everything had a substantially higher delegated equity share (mean of 65%) than did “Continuing investors” who stayed invested (mean of 47%). Among Exiting investors there had been a higher tendency to delegate. In fact, the median Exiting investor held 100% of his equities in actively managed funds. This means that the typical Exiting investor had delegated 100% to money doctors, whom they ostensibly trusted initially, and yet these investors sold all their equities during the crisis.

Talk about a loss of trust!

From the paper:

Clients who have delegated all of their equity investments to actively managed mutual funds are almost twice as likely to sell all of their equity positions during the 2008 financial crisis than their peers who only hold individual stocks…The fragility of stock market participation by these well-diversified textbook investors is remarkable. We argue that it can be attributed to such investors needing a money doctor to give them the sense their investments are under control. Once the financial crisis exposed this sense of control as an illusion, the investors withdrew.

While there are a few more aspects to this paper, this is one of the core observations, and adds impressive analytical support to the money doctor thesis. We look forward to seeing additional creative ways that academics devise to test this intriguing view of the psychology of trust as it relates to delegated investment management.

In the end, as the Exiting investors demonstrated, long-term investment success in active investing is simple, but not easy. Trust alone will not ensure success. For insight into what it takes to achieve sustainable long-term performance, see our post, “The Sustainable Active Investing Framework: Simple, But Not Easy.”

About the Author: David Foulke

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.