Purely passive investing is theoretically plausible but practically impossible. That said, the practical implementations can often be “good enough.”

As a theoretical index investor, you deploy capital, take a long snooze, and wake up some day to consume your portfolio.

Unfortunately, the world doesn’t work like. Allocations change, life happens, and as we cover in this blog post, there are really no indexes that are truly passive.

For example, recently the index giant FTSE Russell proposed to exclude the popular social media app, Snapchat, from its index. In fact, in their memo any company with no voting rights (like Snap) could be excluded from their indexes. This is something that other large index providers have also discussed. The knee jerk reaction might be, “Who cares about Snapchat?” Well, there is a “small” firm called Alphabet (e.g. “Google” as most know it), a stock representing over 1% of the S&P 500, and their shareholders have effectively no voting rights(1).

So perhaps this is a big deal? Who knows.

This recent example is a good anecdote, but there are arguably even bigger issues. Consider index investors invested in many Emerging Market ETF’s, like Vanguard’s VWO. These investors may notice that they don’t own Chinese internet juggernauts Alibaba and Baidu, either(2).

But if index investors think they can go back to sleep after finding a fund like the MSCI Emerging Market ETF (ticker: EEM), that does include Chinese overseas listings like Alibaba, perhaps they should be made aware of MSCI’s most recent proposal. MSCI will likely continue to largely ignore the $7 trillion dollar China A shares market comprising most Chinese domestic companies. Instead of the near 40% of their emerging markets index holding A shares, China could maintain its more modest 28-29% weighting in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

The below pie charts are where we now are likely to stand with MSCI:

If this all seems pretty arbitrary, well, that’s because the process is fairly arbitrary. But a natural question is whether or not these details matter for the passive investor? Are these passive approximations good enough?

Let’s take a step back with a little theory before we address this question.

The Theoretical Global Market Portfolio

My story begins a long long time ago (well, 50+ years ago) in a land far far away (OK, Hyde Park, at the University of Chicago) when basic Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) was still in its infancy. The theory argued that a rational investor who cared about minimizing volatility while maximizing returns should own the so-called “global market portfolio.” Of course, a major assumption (of many) underlying all of this is that markets are efficient — a highly contentious assumption.

The challenge is that the global market portfolio theoretically includes every risk asset, including everything from your human capital to Afghanistan Light-Rail Bonds(3).

These probably don’t exist, but you get the point. Setting aside incredibly esoteric assets that probably don’t have much weight in the theoretical global market portfolio, we will on the investable universe. The research suggests there is a 91 trillion dollar investable universe (as calculated by Doeswijk, et al 2014) and the portfolio looks something like the following:

Perhaps surprisingly, only 40% is tied up in public/private equity and roughly 29% is in government bonds. To simplify the chart even further, you have ~40% equity, ~30% government bonds, and ~30% “other.” Dumping 70% into stocks and government bonds is not exactly appealing given the historically high equity valuations and the current low yields on government bonds. So in theory this allocation makes sense, but in practice this might be questionable. Luckily, theory and practice don’t need to clash.

Gene Fama told the Chicago Booth Magazine on his 50th anniversary at Booth(4) that the best advice he ever got, from Harry Roberts, was that,

You do empirical work to learn from the data…but no hypothesis that you ever test is strictly true…

Likewise, although we need perfect capital markets to truly test the hypotheses stemming from Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), the proxies for the global market portfolio — often constructed by CRSP, S&P, MSCI or FTSE — can be considered “close enough”(5).

Consider by analogy (used by Fama) that true predictions coming from the laws of motion require a perfect vacuum: Does an anvil falling from the Earth’s sky, instead of an anvil falling through a vacuum, change your reaction to step aside? Likewise, an inability to replicate the perfect global market portfolio doesn’t mean we shouldn’t attempt to achieve this goal via indexing.

The Global Market Portfolio in Practice

Let’s start with the equity vs fixed income mix. The standard 60/40 split between equities and fixed income for a moderately risk-averse investor still seems an “adequate” start. An investor can adjust from there according to his/her risk tolerance and cash flow needs. Although past performance isn’t likely to match future returns with current low fixed income yields, Vanguard does give a nice range for a global portfolio’s average historical returns and volatility.

But peeling back the onion a bit further, what should allocations look like within the equity bucket? In other words, that does the global market portfolio theory say about our international stock exposure? Again, we start with research from Vanguard:

International equity represents over half of the global equity portfolio (~52%), and should theoretically represent around half of an investor’s equity exposure if they are trying to allocate to the global market portfolio. A 52% international equities as measured by MSCI feels high and judging from other investors who have only 21% invested internationally, I’m not the only one with a home bias. So many of us aren’t following the theoretical advice presented by the professors primarily hailing from the University of Chicago. Of course, if we blindly followed the advice of the global market portfolio allocations, then back in 1989 more of your holdings would have been held in Japan than in the US(6).

Any investor with equity allocations based on global market weights would have been shot following the epic Japanese equity market fallout in the ensuing 3 years. (they’ve probably been beaten up the past few years as well, as US equity has dominated while international allocations have been lackluster).

Allocate 52% to International Equities? Or is there Wiggle Room?

In theory, we should have our equity book roughly 52% allocated to international markets. But is that an iron-clad rule? Perhaps not. Adding to the argument against a full theoretical allocation to international equities, a team from AQR shows that the volatility of currencies can swamp the diversification benefits. Correlations between currencies and US equities is just too unstable, and often positive, as illustrated by the following AQR exhibit.

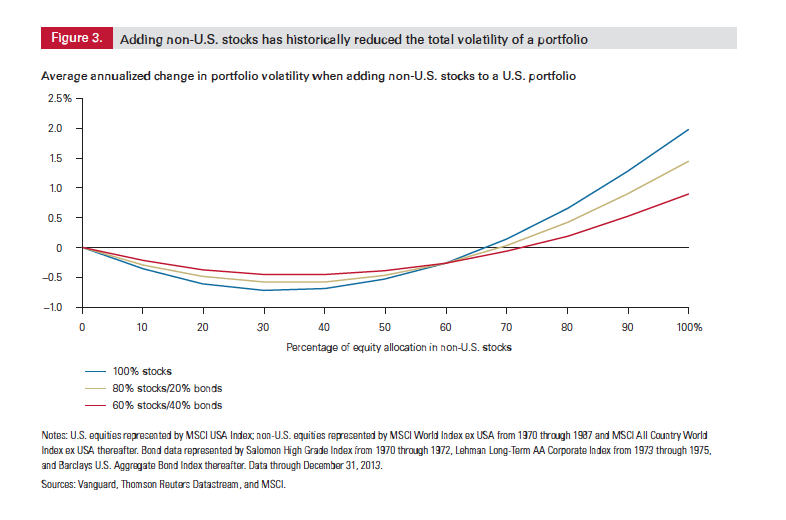

Vanguard also takes look at the question of optimal international diversification. While Vanguard recognizes that the diversification benefits of international equities are real, they suggest that anywhere between 20-40% is “adequate.” Vanguard buttresses this conclusion by showing that most of the benefits of international equity diversification dissipate quickly. So perhaps the “theoretical” allocation isn’t a hard and fast rule?

Concluding Thoughts

There are theories and then there are practical realities. Theoretically, I should have 1 basis point allocated to Afghani Light-Rail-Bonds, but practically accessing that paper probably isn’t worth it for my portfolio (or my life expectancy!)

In this short piece, I highlight the concept of the global market portfolio, identify some of the recommendations stemming from this theoretical construct, and discuss some arguments for why we may not need to consider this theory the gospel. The general takeaway is that we often invest in markets in a theoretically sub-optimal way, but in a way that is adequate from a practical standpoint. We also focused on equity allocations. Fixed income can get trickier. The 17.4 trillion dollars of bonds represented by the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Index is less than half of the investable $39.1 trillion universe of US domestic bonds (as reported by Guggenheim). Is the AGG index good enough?

Or do we need to dig deep into the 39.1 trillion dollars to maintain our tie with the global market portfolio’s theory?

Possibly, but perhaps not. We can punt that discussion to another article.

In the end, investors should focus on what they can measure and control with more certainty, namely fees and taxes. Luckily, that task doesn’t take a Ph.D. (or a high-priced investment advisor). Most ETFs are already structured to minimize capital gains and have relatively low fees. Tax loss harvesting strategies and maximizing the tax deferral nature of 401Ks and IRAs are also straightforward. So forget about optimizing your portfolio to match a global market portfolio construct and go back to sleep. You probably won’t miss much during your slumber.

References[+]

| ↑1 | source |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Alibaba, at $350bn, is China’s 2nd largest company by market cap and 10% of it’s investable market! |

| ↑3 | Fama, Eugene F., and Miller Merton H., 1972, The theory of finance, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston., pages 20-21 |

| ↑4 | “Father of Modern Finance”, Chicago Booth Magazine, Fall 2013 |

| ↑5 | Fama, Eugene F., and Miller Merton H., 1972, The theory of finance, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston., page 22 |

| ↑6 | the scale to which depends on your source |

About the Author: Jonathan Seed

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.