I recently experienced one of those fortunate confluence of events that helped me better grasp the relationship between forecasting (which I feel is futile) and my contrarian biases (which are strong). I better realize now that both a contrarian bias and a value approach to investing involves forecasting, just with a humbler twist.

This journey started with a recent attempt to digitize my life. I have been scanning and, in the process, have revisited my nearly three decades of investing. My successful contrarian led investment outcomes, especially in 2000 and 2008, were marred by shockingly poor forecasting attempts.

Later, at a lunch I attended, legendary contrarian Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital, consistent with his book Mastering the Market Cycle, admitted that he never forecasts. He does, though, believe in the art of navigating through market cycles. His message rang true.

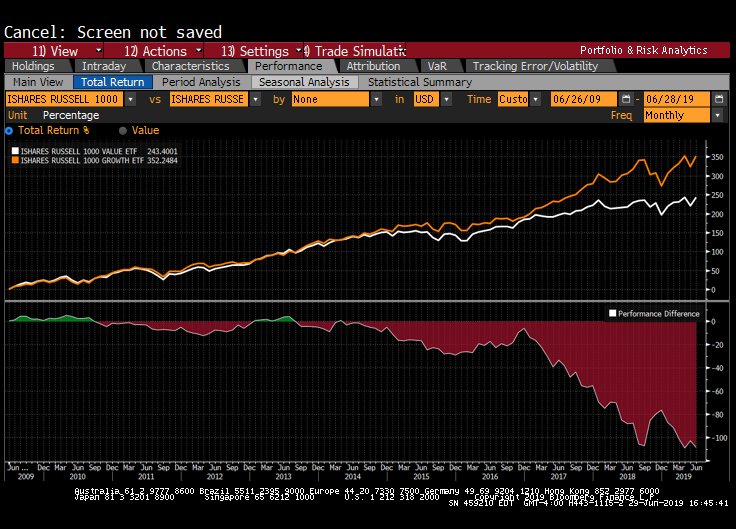

And lastly, a number of recent articles have opined on both forecasting and the poor recent performance of value investing. The collection includes a study in this blog by Jack Vogel and team who ran a fun test of how the highest-priced stocks (at least relative to sales) have performed, an expansion on the dissection of value investing performed last year by O’Shaughnessy Capital Management. Spoiler alert: growth has trounced value over the last decade as nicely covered on this blog by Matthew Bartolini and value stocks continue to be dogs.

Source: Bloomberg. 10-Year Performance Differential between the IShares Russell 1000 Growth and Value Funds

My small epiphany? Both value and contrarian investing have thrived because humans are poor forecasters. An embedded assumption in this approach is that poor forecasting among the broader investing public will continue. When scared, investors assume the worst and this outcome doesn’t occur; and when euphoric, they forget the laws of gravity and valuations no longer matter. In short, investors incorrectly extrapolate patterns into the future. But value and contrarian investors also believe trends will most often revert to their averages, the economic advancements we’ve experienced will continue despite the occasional recession and humans will continue to make heuristic errors tied to their misplaced confidence in either themselves or in their anointed gurus.

As occurred over the last 10 years, all this may not keep reocurring. Investors ability to predict the future may improve. But I’m going to keep making those value and contrarian bets based on the forecast that history does in fact repeat. Overconfidence, anxiety, and extrapolation of what we see are too innate within us to avoid cycles. In other words, I’m going to continue 1) paying attention to price and 2) “be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful”.

My Miserable Forecasts Keep Good Company

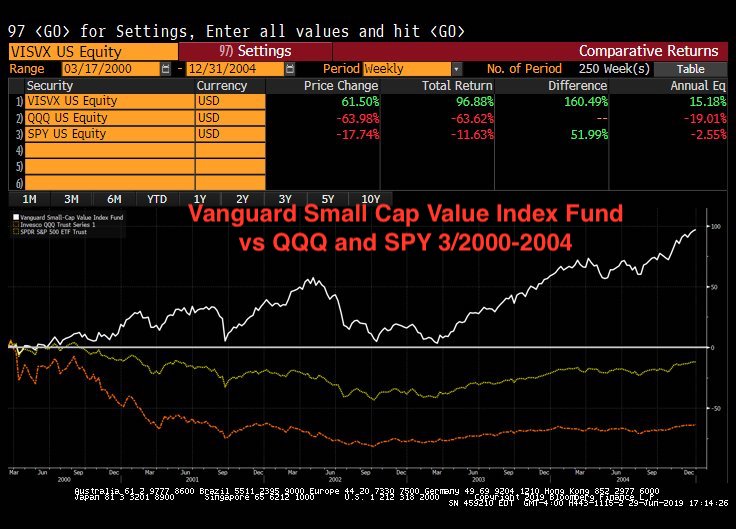

I keep a track record of my successes and failures in the hopes I can learn something, perhaps at a minimum, some more humility. Philip Tetlock preaches in his book Superforecasting that because of human biases, including overconfidence, experts have a poor track record of success. One way to keep overconfidence in check is to keep score. I remembered, correctly, my hesitation to invest in hot internet stocks in 2000 in favor of the Vanguard Small-Cap Value Fund, avoidance of financials (including the purchases of out of the money put options) into the lead up of 2008 and the purchase of many “cheap closed-end funds and preferred shares in the depths of the financial crisis. Those fond memories of being right, certainly gave my ego a boost.

What I didn’t fully recall was that I avoided the tech sector as early as 1996 missing the runup and started buying them “cheap” in later 2000 (remember Compaq?) two years before the bottom. Yes, I also bought “really cheap” closed-end funds and preferred shares in earnest in the financial crisis in September of 2008 only to watch them get really really cheap weeks later. Finally, I purchased many of my puts as early as the summer of 2007 which expired in early 2008. I would have done much better with puts that lasted longer. If the empirical evidence that my crystal ball is cracked isn’t enough, I have a good friend who reminds me regularly that I told him in 2006 that I thought the troubles brewing in the subprime market would be contained. Most of the risk, I assured him, was held overseas in the form of CDOs. I’m also on record in this blog for stating back in early 2016 that bonds have no value…when the 10-year treasury was closer to 2.5%. It’s now closer to 2.0%.

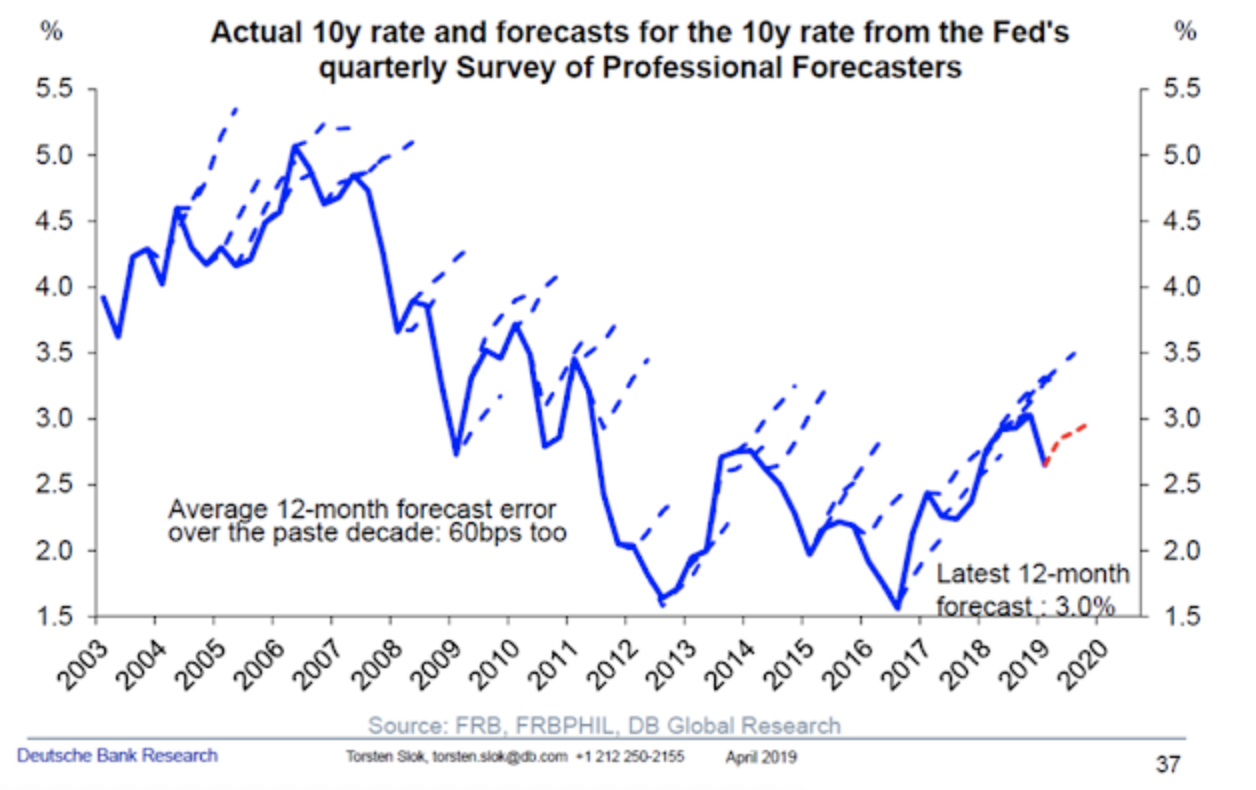

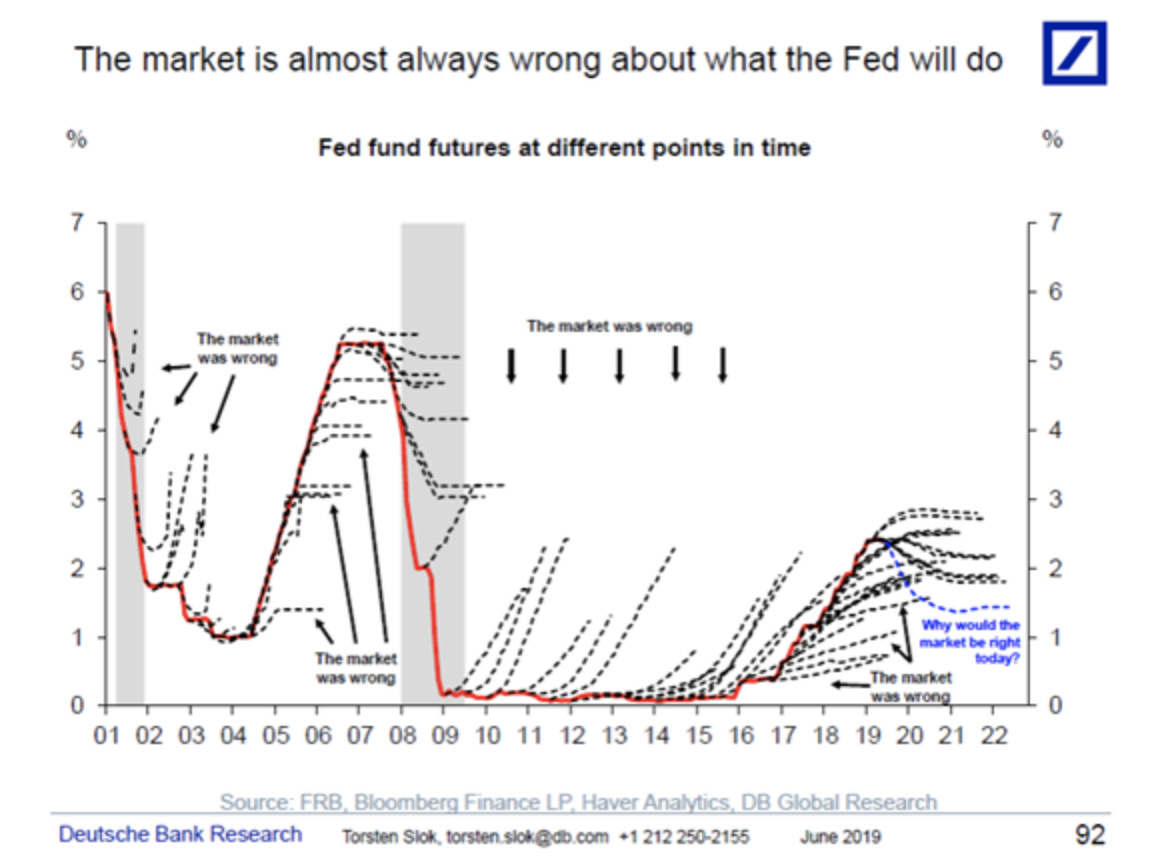

Luckily for my ego, I’m not the only one inept at predicting the future of market prices. As John Cochrane has shared on his blog “The Grumpy Economist”, professionals are also lousy market financial forecasters. Torsten Slok of Deutsche Bank created some fun graphs showing when it comes to rates, both the experts (note that this graph is from April when rates were roughly 50 basis points higher)…

…and the futures market have been consistently wrong.

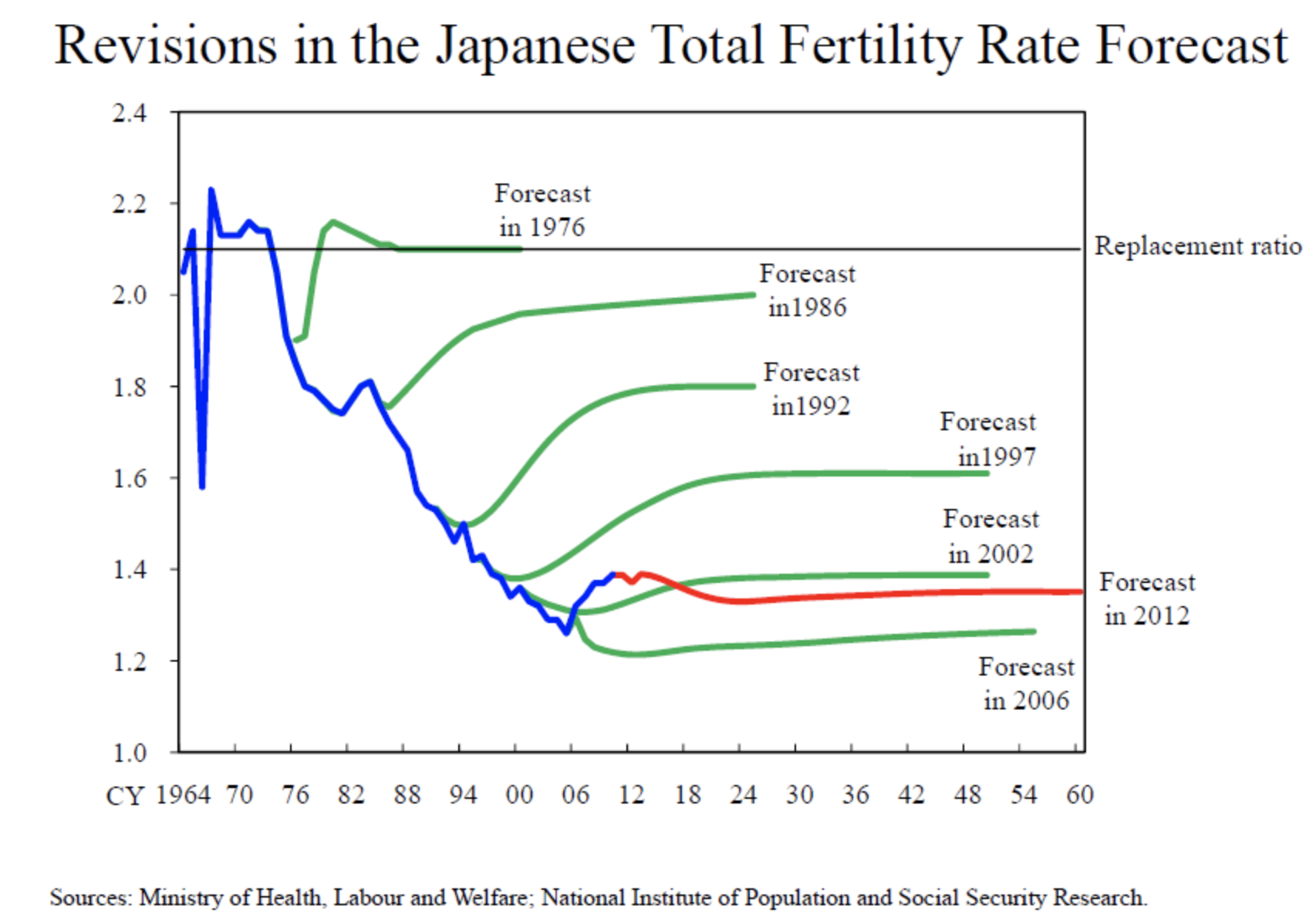

And it’s not just predicting interest rates where the experts fail. Again, John Cochrane provides this graph illustrating in his blog post on James Surowiecki’s The New Yorker article, “Punditonomics” that even demographers have lousy track records.

It’s easy to skewer those that try and predict the future, especially those trying to market-time (e.g., Irving Fischer in 1929 declaring stocks have reached a “permanently high plateau”) or predict market bubbles (e.g., Alan Greenspan’s 1996 speech of the “Irrational Exuberance” of stock prices or Robert Shiller’s 2015 concern regarding a stock market bubble).

But no doubt some managers and forecasters are more talented than others. Larry Swedroe on this blog recently reviewed studies that showed whatever alpha active managers achieved went to themselves in the form of higher fees. Warren Buffett estimated in his 2016 annual letter (p.23) that he has “identified – early on – only ten or so professionals” he thought likely to be able to beat the S&P 500. Fama and French (2010) (1) likewise found that although a small subset of investors is likely talented enough to overcome their fees (3% in their study cited on the right), it is impossible to determine which among the elite are simply lucky or good.

Contrarian Bill Miller, as one example, was heralded as one of the savviest portfolio managers throughout the 1990s and the first half of the new millennium. By 2005, after having beaten the market 15 years in a row, he had cemented his guru status. His willingness to keep investing in out of favor stocks like Amazon throughout the technology bust of the early 2000’s, though, served him much less well in 2006, 2007 and 2008 as he increased his weight in out of favor financial stocks.

Bill Miller fell from his pinnacle in 2005 to ranking dead last in its Lipper category by 2011, but we don’t need to pile on. In fact, we admire the quote from his 2005 WSJ interview: “We’ve been lucky. Well, maybe it’s not 100% luck. Maybe 95% luck.” And we agree with his buy and hold, contrarian biases. What needs to be retold, though, is that even his outperformance over 15 years is likely to have occurred by chance at some point, by some manager. Caltech physicist and author of The Drunkard’s Walk Leonard Mlodinow calculated that with well over 1,000 active mutual fund managers over the last 40 years, at least one of them would have had a 3 out of 4 chance of beating the market every year for 15 years straight.

A Refreshing Opening by Howard Marks: “I don’t forecast”

Wary of the value of another “legendary investor’s” predictions when joining the lunch with Oaktree’s Howard Marks, I was quickly put at ease. He shared the anecdote of him patting himself on the back for maneuvering and profiting during various market cycles only to be reminded by his son and co-author that over a 50-year career, what he really did was correctly foresee a small total of 5 cyclical ebbs and flows. As he acknowledges at the end of his book Mastering the Market Cycle, “detecting and exploiting the extremes is really the best we can hope for” (p 265).

He doesn’t try and forecast or wait for the bottom to start buying or the top to start selling. Instead, he makes his investment decision based on a combination of valuations and investor behavior. Like Warren Buffett, he’s greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy. He’s both a true contrarian and a value investor.

His timing is also often lousy. He recants in his book that he raised capital for his leveraged loan fund immediately following Lehman’s collapse in September of 2008 when prices were close to 88 only to have to go back again to raise money when they subsequently collapsed to near 70 (p. 130). He acknowledges that no one, including himself, knows for sure what the future holds. All he does is try to increase his odds.

He goes on (and on) proclaiming that “In the end, trees don’t grow to the sky, and few things go to zero. Rather, most phenomena turn out to be cyclical.” (p.34) “Most” is the keyword. But the Giant Redwoods of Northern California grow awfully high and plenty of individual stocks go to zero. He offers Xerox as an example of one of the leaders of “Nifty Fifty”, a group of fast-growing stocks in the late 1960s that analysts and fund managers touted as invincible and untethered to common valuation measures. He then shares Xerox’s metamorphosis into a value stock by October of 2002 when it “returned to profitability sooner than expected.” (p281). As can often be the case with value stocks, Xerox’s price, earnings per share and P/E ratio have been largely flat since. Growth never returned.

Bond yields can also go to zero. Switzerland’s 10-year treasury rate is negative 0.5%! James Grant in Barron’s recently stated: “Humans eat, sleep, and extrapolate.” He then goes on to add, “In [interest] rates, it actually tends to work.” The great bear market in interest rates started in 1946 and lasted 35 years. The current great bull market in interest rates appears to be regaining steam again in year 38. Maybe things are actually different now. Those may be the most dangerous words in finance, but that doesn’t mean they are always wrong.

What’s Happened to Value Stocks?

Value investors have traditionally benefited by both avoiding hyped stocks that eventually return to earth and by investing in “dogs” that eventually shake themselves off and return to health. Fama and French (2007) (2) looked at value stocks as defined by their price to book (P/B) ratios and found their value premium comes largely from out-of-favor value stocks returning to profitability, a respective rebound in price and thus a higher P/B multiple when they are sold for a profit. O’Shaughnessy Asset Management (OSAM) finds similar causes when they dissect value’s performance in terms of price to earnings (P/E) ratios: value stocks become cheap as their earnings falter but recover when the market begins to correctly anticipate higher earnings.

Perhaps more interestingly, OSAM also finds that more recently, the earnings recovery of value stocks hasn’t been as strong. Jack Vogel on this blog also confirms that glamour stocks, as defined by those with the highest Price/Sales ratios, have slaughtered the market over the last 5 and 10 years. A cursory glance of those stocks (e.g., Visa, Netflix, and Adobe) confirms OSAM’s intuition that those “expensive stocks” have recently lived up to their hype. The market forecasts this time were correct and the imbedded forecast of value investing, that earnings growth and thus valuation levels will eventually converge, hasn’t happened.

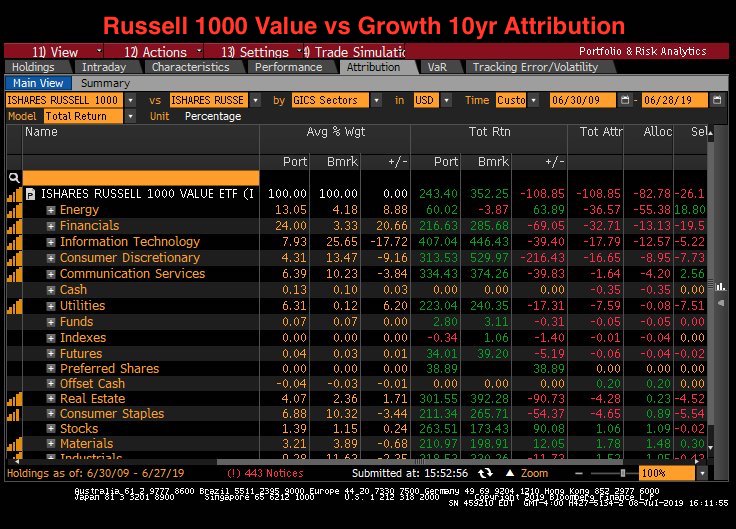

This recent failure of value stocks also appears at the industry level as seen by looking more deeply at the relative performance attributes of value vs growth funds over the last 10 years. I use Bloomberg to compare the relative performance attribution of IShares Russell 1000 Growth ETF <IWF> versus the IShares Russell 1000 Value ETF <IWD> based on GICS sector definition (no, I don’t think these funds offer the best way to capture either growth or value nor that GIC sectors offer the best way to capture attribution, but I’m trying to keep it simple). As shown in the table below, nearly 80% of the last 10 years’ outperformance by growth stocks has come from relative sector allocations. Specifically, value funds like IWD have invested relatively heavily the energy and financials sectors which have lagged the market as low oil prices and interest rates have weighed against any earnings rebound. On the flip side, growth funds like IWF have more heavily allocated to information technology stocks like Apple and to a lesser extent, consumer discretionary stocks (read Amazon). These stocks continue to grow like Giant Redwoods.

Relative return attributions as calculated by Bloomberg is separated into that generated from GIC Sector allocation (Alloc) and stock selection within GIC Sectors (Sel)

What to do? Better to Ask What Not to Do

So now what? For starters, I’d forewarn you against trying to predict interest rates, oil prices or the likelihood of Netflix, Amazon and Apple falling from their perch. I’ve learned that I’m terrible at predictions and have yet to find a proper way to tell amongst the experts who is lucky rather than good at forecasting.

Still, I’m going to listen to Howard Marks, Warren Buffett, reams of studies and common sense that all support paying attention to price and the mood of the market. I’m going to predict that the experts get it wrong again as the future is too unpredictable to forecast. Yes, I realize that itself is a prediction. I also understand that Amazon could take over the world and interest rates could stay low forever. I’ll make sure my clients survive if they do by keeping them diversified.

Specifically, based on price, I’m still not going to lock my money up for 10 years at 2 or even 3% in government bonds. That is too paltry a return after inflation, a risk for which the market seems fearless. I also remain suspect of the hedging benefits of bonds versus stocks should inflation return.

I’m also going to continue to be a contrarian and largely avoid high yield muni bonds. As recently reported in the WSJ, more money than ever is pouring into the riskiest bowers, including my state of Illinois as well as private charter schools, retirement communities and railroads that lack taxing power.

Finally, I’m happy to keep investing in closed-end funds, leveraged loans, and preferred shares (at least the version with floating rate coupons) when those sectors appear unloved and cheap as they looked first this November then even more so in December. As I did before, I may get in too early and get out too late, but I still like the historical evidence that timing isn’t everything for value to matter.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Eugene F. and French, Kenneth R., Luck Versus Skill in the Cross-Section of Mutual Fund Returns.” Journal of Finance, Vol. 65, No. 5 October 2010 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Fama, Eugene F. and French, Kenneth R., The Anatomy of Value and Growth Stock Returns. Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 63, No. 6, 2007. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1071124 |

About the Author: Jonathan Seed

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.