Board leadership positions elude diverse directors

- Laura Casares Field, Matthew Souther, and Adam Yore

- Journal of Financial Economics, 2020

- A version of this paper can be found here.

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category

What are the Research Questions?

The good news is that the percentage of female and minority directors has substantially increased in the past 20 years. The bad news is that we still have a lot of work to do. It turns out that more diverse boards come with a host of advantages for the corporations they represent. Therefore understanding and working towards more diverse boards is crucial moving forward. In an effort to better understand corporate diversity, this study examines the extent to which women and minorities serve in leadership roles on corporate boards, specifically as nonexecutive chairman of the board, lead director, or chair of a major board committee (audit, compensation, nominating, or governance).

The authors ask the following questions:

- What is the status of the board leadership gap for women and minorities?

- Is the board leadership gap influenced by a lack of experience and/or qualifications?

- Why then, are diverse directors are less likely to serve in board leadership roles?

- What are the possible solutions to reduce the leadership diversity gap?

What are the Academic Insights?

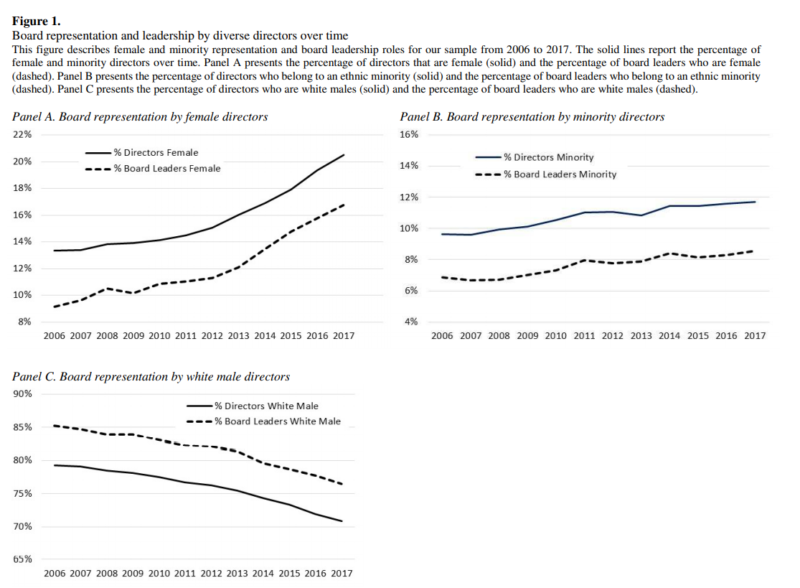

By using the allocation of leadership appointments within the corporate boardroom as a laboratory to explore the labor market effects of gender and race, the authors study a large sample of nonemployee directors on US corporate boards from 2006 to 2017, which includes 126,044 director-firm-year observations representing 19,686 individual directors serving at 2,254 unique firms.

They find the following:

- Confirming prior evidence, diverse directors are represented on the four major board committees. Despite being highly qualified, diverse directors are significantly less likely to be appointed to board leadership roles. In fact, once on the board, women, and minorities have lower representation in board leadership roles relative to white males. While the representation of diverse directors has improved over our sample period, their representation in board leadership roles has lagged their representation on the board. To eliminate the gap between representation and leadership during a time of increasing diversity, the proportion of diverse board leaders would have to increase at a greater rate than overall diversity: 48 years for females and 126 years for minorities.

- NO. The study showed that diverse directors exhibit a greater number of professional credentials, have more extensive outside board experience as well as other firm committee experience, and come from larger director networks than their white male counterparts. Moreover, in a multivariate setting in which the study control for director qualifications and experience, the authors continue to find a substantial leadership gap: diverse directors are nearly 4% less likely to serve as non-executive chairman and are 5% less likely to serve as lead director. Given a naïve appointment probability of 11%, this implies a 32% −47% reduction in the likelihood of appointment relative to a nondiverse director. Similarly, diverse directors are between 13% and 27% less likely to serve as chair of one of the four major committees (audit, compensation, nominating, or governance). In general, the authors find that for each skill or experience measure we examine, diverse directors are at a relative disadvantage to their non-diverse counterparts.

- One possibility could be those diverse directors may choose to serve on more boards rather than commit substantial resources to serving in leadership positions on fewer boards. However, the authors find no evidence that this may be the case. Another possible explanation is that diverse directors may prefer not to serve in leadership positions, potentially due to varying degrees of risk preferences. Again the authors do not find evidence for this case. A third possibility could then be that women and minorities are overlooked for leadership positions because they are less effective. Strikingly, however, the authors find that quality of financial reporting is higher with a diverse chair on the audit committee, the sensitivity of CEO turnover to performance is similar for boards with or without a diverse non-executive chairman or lead director, and abnormal CEO pay is similar for boards with or without a diverse chair on the compensation committee. Additionally, diverse directors receive significantly higher voting support than do their nondiverse counterparts, suggesting that shareholders view them as effective. Could it be biases then?

- The authors find that firms explicitly stating in their proxy statements that they consider race and gender in their board nomination policy, the likelihood to have diverse directors serving in board leadership roles increase by 6–9%. Additionally, having a diverse director on the nominating committee increases the likelihood of a diverse leadership appointment (outside the nominating committee) by 5%. Differently, simple diverse board representation is not sufficient.

The authors perform robustness checks to control for omitted variables and self-selection biases and continue to find that diverse directors face challenges in obtaining board leadership positions. It is the first to explore the implications of race and gender following the initial appointment to the board. It highlights the importance of having women or minorities in positions of leadership for promoting equity among employees.

Why does it matter?

This study is interesting because it points to several areas of concern with regard to board representation. Diverse directors stand out from their peers in terms of academic and professional credentials, possess more outside board and committee experience, and enjoy greater support from shareholders in director elections. Despite all of this they remain less likely to be appointed to key board leadership positions. We must do better!

The Most Important Chart from the Paper:

Abstract

We explore the labor market effects of gender and race by examining board leadership appointments. Prior studies are often limited by observing only hired candidates, whereas the boardroom provides a controlled setting where both hired and unhired candidates are observable. Although diverse (female and minority) board representation has increased, diverse directors are significantly less likely to serve in leadership positions, despite possessing stronger qualifications than non-diverse directors. While specialized skills such as prior leadership or finance experience increase the likelihood of appointment, that likelihood is reduced for diverse directors. Additional tests provide no evidence that diverse directors are less effective.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.